Athens was inhabited from the fifth millennium bc onwards, with evidence of settlements around the Agora and Acropolis dating to the fourth millennium bc. It began to flower in the late Bronze Age. Around 1600 bc a palace was constructed on the Acropolis, whose steep sides were fortified with ‘Cyclopean’ walls. The building apparently remained intact until the tenth century, when it was destroyed by earthquake or fire. Its location became the focus for rituals honouring kings, including Erechtheus and Cecrops, who were believed to have lived there.

By the seventh century bc the Acropolis was Athens’ religious heart: in 632 bc, after a failed coup, political activists sought asylum in its temple of Athene Polias. While early sixth-century bc reforms (attributed to Solon) sought to unite the coastal, rural and urban peoples, the second half of the century was dominated by Peisistratus, a benign tyrannos, who increased Athens’ kudos through building works, by enhancing the Panathenaic Festival and Eleusinian Mysteries, and by creating a new drama festival. After Peisistratus’ son Hippias was expelled in 510 bc, Cleisthenes introduced isonomia (equality under the law), which gradually developed into demokratia (rule by the people).

In the early fifth century bc, Athens faced an existential threat from the Persians. Victory at Marathon (490 bc) provided temporary relief, but in 480 bc Athens was overrun and its temples burned. Days later its navy (built from revenue from silver mines at Laurium near Sunium) helped win a resounding victory at Salamis. In 479 bc, after routing the Persians at Plataea, Athens led an alliance of Greek states, the Delian League, aimed at neutralizing the Persian threat. It soon became an Athenian empire. Athens’ fleet patrolled the Aegean and in 454 bc the League’s treasury moved from Delos to Athens.

Under Pericles (a tyrannos in all but name) Athens pursued an aggressively expansionist policy. This led to the Peloponnesian War between Athens’ empire and a confederacy of states led by Sparta; the eventual outcome was Athens’ defeat (404 bc). It was an ignominious end to a century in which, home to many outstanding philosophers, writers and artists, Athens had shone – more than living up to Pericles’ boast that it was ‘an education to all Greece’.

Athens soon recovered. In the fourth century bc it resounded to philosophical debate: Plato founded his Academy, Aristotle his Lyceum and Epicurus his ‘Garden’ school, while Zeno taught in one of Athens’ stoas, which gave his followers their name: Stoics. Like its allies, Athens was defeated by Philip II of Macedon at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 bc, but it was relatively well treated by Alexander the Great and remained largely unscathed in the upheavals following his death.

When Athens supported Rome’s enemy Mithridates VI of Pontus, it was sacked by Sulla in 86 bc.

Rebuilt and restored to grace, it became a ‘university’ town, respected for its history and architecture, and patronized in the second century ad by wealthy donors such as Herodes Atticus and the emperor Hadrian. Athens was plundered in the third century ad by the Heruli and in ad 396 by Alaric the Goth, after which its importance diminished. From the ninth to the fifteenth century trade with Italy saw its fortunes rise once more, and in 1205 after the Fourth Crusade it became a Duchy. But in 1458 Athens fell to the Ottoman Empire, heralding a long period of decline, during which the Parthenon was variously used as an ammunition dump (suffering a direct hit during Venetian bombardment in 1687) and a mosque, before being stripped of its sculptures by Lord Elgin in 1801 under circumstances which are still debated today.

In 1834 after Greek independence, the nation’s capital was moved from Nafplio to Athens, then little more than a village, and in 1896 the graceful neoclassical city hosted the newly revived Olympic Games. However, after the population exchange with Turkey in 1922, the Second World War and the Greek Civil War, Athens mushroomed, especially after the late 1950s. It hosted the Olympic Games of 2002, encouraging new building work and enhancing the city centre.

Athens in History & Today Photo Gallery

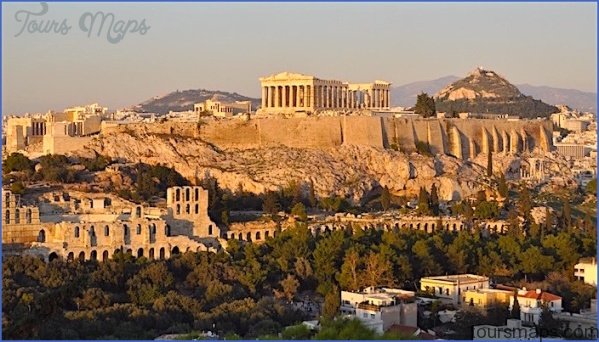

Athens is a treasure trove of archaeology. At its heart is the Acropolis. A steep climb leads through the Propylaia with the graceful Temple of Athene Nike on a bastion (right). Grey Eleusinian limestone forms a sacred threshold. Two temples dominate the Acropolis: the Parthenon, once home to Pheidias’ gold-and-ivory statue of Athene; and the Erechtheum (or Temple of Athene Polias), containing several distinct chapels, the roof of whose Porch is supported by sculptures of six girls, the Caryatids (casts). In antiquity it was of greater religious significance than the Parthenon. The foundations of the earlier Temple of Athene Polias, burned by the Persians in 480 BC, lie between the Parthenon and the Erechtheum.

The stunning Acropolis Museum is housed to the south on Dionysiou Areopagitou. Further west along this street are the Arch of Hadrian and Temple of Olympian Zeus, with fine views of the Acropolis.

On the Acropolis’ southern slopes are the Theatre of Dionysus and the Odeon of Herodes Atticus (still used for performances). Just west of the Acropolis is the Areopagus (Hill of Ares), not for the faint hearted – there is a steep climb and slippery surface. Below this is the Agora, dominated to the east by the Stoa of Attalus (reconstructed by the American School of Archaeology, now housing the Agora Museum) and on the west by the Temple of Hephaestus (sometimes wrongly called the Theseum). Further east are the Roman Agora and Tower of Winds.

West from the Agora is the Ceramicus (Kerameikos), one of classical Athens’ cemeteries, whose boundaries include part of the ancient wall. From the Sacred Gate one road led to Eleusis, another to Plato’s Academy. The haunt of tortoises and butterflies, the Ceramicus is a haven for the harassed traveller. It has an excellent museum.

The National Archaeological Museum contains finds from Athens and all Greece. Innumerable treasures include gold death masks from Mycenae, Cycladic figurines, Classical sculptures including the fine bronze Poseidon (or Zeus), the Varvakeion Athene (a marble scale copy of Pheidias’ statue for the Parthenon) and a stunning second-century BC life-size bronze galloping racehorse.

Several days are needed even to skim the surface of Athens’ sites and museums. Many close early and are popular with coach parties, so it is advisable to time visits for early morning. To avoid being overwhelmed, take frequent breaks for refreshment and reflection.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Theseus & Peirithous

- The Voyage of the Argo Begins

- Minos, his Loves & his Family

- The Centaurs

- Cecrops & Erichthonius