IT IS against the law of Islam for anyone to paint a portrait. On the Day of Judgment, the prophet Mohammed is reported to have said, painters will be doomed to hell for their blasphemous attempts to compete with God by creating life. If the religious laws were practiced as much as they were preached, Moslem artists would never have represented any living thing.

Yet the Moslems did develop splendid schools of portraiture and historical painting, for they have been no more noted for strict obedience to religious laws than members of other faiths have been.

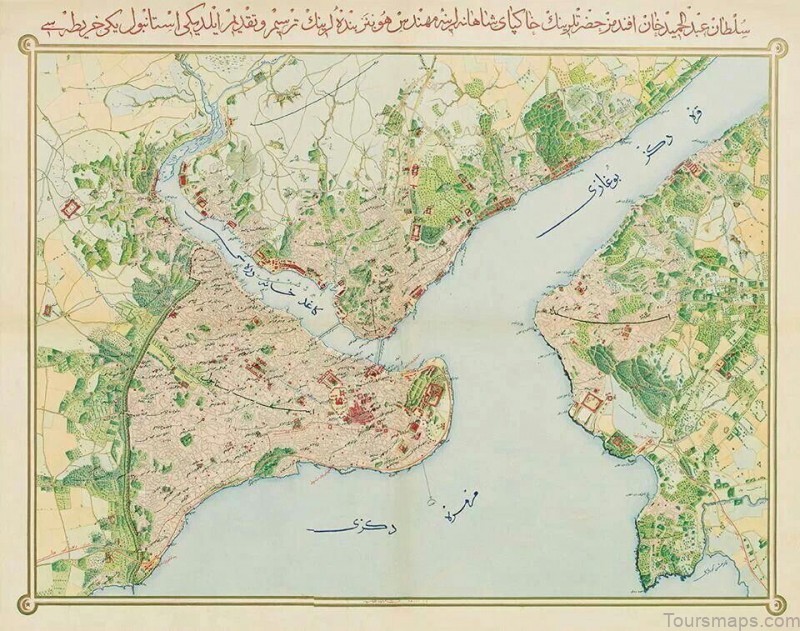

Istanbul Map Free Download Photo Gallery

Over the centuries Islamic artists have painted pictures of dervishes, sultans, and saints, subjects from the Koran, the Bible, and Arab and Persian legends, and vignettes of everyday life, from women in childbirth to street sweepers at work. Palace walls were decorated with hunting scenes, or portraits of conquered kings, or dancing girls, and, in one case, even a representation of a Christian church, complete with praying monks.

The Ottoman sultans of Turkey were in the forefront of Islamic society in their patronage of art, commissioning numerous portraits of themselves, their favorites, and their families. But this work was, often as not, done in secret, to keep the sultan’s subjects from discovering that he was breaking the religious law. Despite the secrecy, the Ottoman style of portraiture and miniature painting evolved into a distinctive and sophisticated art form, as splendid in its own way as Ottoman architecture, which is seen in so many beautiful mosques throughout Turkey and is usually considered the noblest accomplishment of Turkish art.

It was not until the eleventh century AD that the Turks themselves began migrating into the country. Their original home was in central Asia, where they were nomadic horsemen roaming the steppes. Even in that quarter of the world—seemingly so remote—the Turks were subject to the influence of the great centers of world civilization. Caravans made their way across the vast Asiatic plains, bringing Greek and Roman coins, silverwork and goldwork from Persia, and paintings and silks from China.

At the same time, the Turks ranged widely over the steppes; remains of their own ancient art—showing these strong and varied foreign influences—are found throughout regions of Asiatic Russia, in Outer Mongolia and Afghanistan, and in the part of China that today is called Sinkiang, although it was formerly known as Eastern Turkestan. By the end of the seventh century the Turkish tribesmen were in contact with the Arabs, whose armies had penetrated as far as the Turkish towns of Bukhara and Samarkand. The Arabs found the Turks to be formidable warriors, and soon the palace guard of the Arab caliphs at Baghdad was composed of Turkish mercenaries. From being the caliph’s servants, they became his masters.

By the ninth century the Seljuk Turks—tribesmen whose chieftains claimed descent from an ancestral hero named Seljuk—had made the caliph into a figurehead. In 1055 they took over most of the great Arab empire for themselves; a few years later, in 1071, they defeated the emperor of Byzantium at Manzikert in Asia Minor and began settling in that country. Shortly before the year 1300 a few hundred families of another Turkish tribe left their central Asiatic pastures near the river Oxus to settle in the domain of their Seljuk kin. Under their leader, Osman, they soon moved into western Asia Minor, and as the Seljuk empire broke into fragments, they extended their sway to gain control eventually over the entire region.

Osman’s descendants, the Osmanli or Ottoman sultans, continued to rule Asia Minor until the establishment of the Turkish republic in 1922. One of the most famous of them, Mohammed II, captured Constantinople in 1453 and put an end to the diminished Byzantine empire. Once his capital was established there, he sent his armies o in all four directions. The swiftly moving Turkish horsemen returned victorious—and rich—and the sultans soon ruled an empire on three continents. Osman’s descendants led glorious but dangerous lives. Whenever a new sultan ascended the bejeweled imperial throne, he had his brothers strangled to rid himself of rivals.

Later, when the Turks became more civilized, the sultan’s brothers—and often his sons—were merely imprisoned in cages, next to the royal harem, to keep them from mischief. But whenever one of them was lucky enough to reach the throne, he could style himself: “Sultan of the Sultans of East and West, fortunate lord of the domains of the Romans, Persians, and Arabs, Hero of creation … Sultan of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, of the extolled Ka’aba and Medina the illustrious and Jerusalem the noble, of the throne of Egypt and the province of Yemen, Aden and Sanaa, of Baghdad and Basra and Lahsa and Ctesiphon, of the lands of Algiers and Azerbaijan, of the region of the Kipchaks and the lands of the Tartars, of Kurdistan and Luristan and all Rumelia, Anatolia and Karaman, of Wallachia and Moldavia and Hungary and many kingdoms and lands besides …”

Turkish royal politics being what they were, it was a fortunate sultan who stayed on the throne long enough to memorize, or even recite, this formula. The court artists who were called upon to depict so august and all-powerful a personage had a difficult task. They showed the sultan bigger than the people around him, his rich robes billowing out to all an inordinately large share of the picture space. The painters, like almost everyone else who lived and worked in the Grand Seraglio, the enormous royal palace at Constantinople, were his slaves, about on a level with the servant who carried in the clock when the sultan wanted to know what time it was, or the man who bore an extra royal turban in public processions and bobbed it up and down to save the sultan the trouble of acknowledging the applause of the populace.