REFLECTIONS IN A GLOWING GARDEN

IN SEPTEMBER, THE fields around Llanover House, just south of Abergavenny in the Usk Valley, are busy with Black Welsh Mountain sheep feasting on lush grass in preparation for the breeding season. To the north-west, the distinctive shapes of the Sugar Loaf and the Blorenge rise from the Black Mountains, while in the west, the oak- and beech-clad slopes of the Brecon Beacons begin to glow in shades of russet and gold. Elizabeth Murray is the seventh generation of her family to look after the 15-acre garden at Llanover, set within an estate of farmland and forest.

“We work hard to keep the garden open to its surroundings,” she says. “With so many trees, we have to be careful with spacing, so it doesn’t feel closed in. My husband, Ross, has a talent for seeing which trees need to come out, and, unlike me, he doesn’t have an emotional attachment to them, which is helpful at times.” Movement and sound Elizabeth’s ancestor Benjamin Waddington bought the farmhouse at Llanover in 1792, added an elegant neoclassical front and began shaping the garden by harnessing the stream that runs through it, called the Rhyd-y-Meirch or ‘Ford of the Stallions’.

“He was attracted by the tumbling stream,” says Elizabeth. “He channelled it into ponds and over cascades, which change the sound of the water as it flows. It’s a tremendous asset, bringing movement, light and sound into the garden, as well as lots of wildlife.” Wild trout swim through the stream, dippers dart and bob along it, and, in drier parts of the garden, there are adders and grass snakes. “We have so many different habitats. Llanover is home to far more than just my human family.”

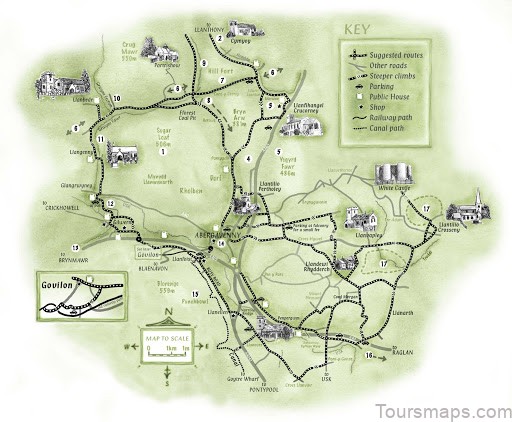

Map of Abergavenny – Abergavenny Guide – Llanover House Photo Gallery

Entering the garden on its south-west edge, the stream emerges into the Upper Arboretum through a shelter belt of high-pruned Douglas fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii; their lower branches removed. They are underplanted with birch trees, Betula ermanii ‘Grayswood Hill’, boasting bright cream and pink bark. Here, the stream is natural and unmanicured, fringed with ferns and wild flowers. The damp meadows each side are home to water-loving trees, including deciduous conifers, such as the swamp cypress, Taxodium distichum, with needles that fade to copper before falling, and the golden larch, Pseudolarix amabilis; a tree that certainly lives up to its name in autumn when it turns an intense yellow.

In recent years, Elizabeth has planted groups of shrubs beside the stream, including coloured-stemmed willows and dogwoods, which add colour in autumn and winter. “They served us well during the storms in February of this year,” she says. “Although some soil was washed away, I think the force of the water would have taken great chunks out of the banks without the stabilising effect of the roots holding them in place.” Here too is a paperbark maple, Acer griseum, with its peeling bark a marmalade-orange and translucent as the sun shines through it, and groups of hydrangeas, with papery bracts and leaves blotched purple and red as the growing season winds down.

It is one of many paperbark maples in the garden; most propagated from seed collected from a tree planted by Elizabeth’s grandmother Lady Mary Herbert to commemorate the silver jubilee of King George V in 1935. Running parallel to the stream, an avenue of sweet chestnuts, Castanea sativa, lines the drive; their leaves fading to a dull yellow before falling among the prickly-cased fruits that litter the ground. At the base of some of the trees are colonies of Cyclamen hederifolium, with pretty pink and white flowers and heart-shaped leaves marked in silver. Unfortunately, the chestnuts have succumbed to disease and are dying, leaving Elizabeth and Ross undecided as to what course of action to take, at least for the moment.

“We’re not sure whether or not to take them all down at once and replant,” says Elizabeth, “and if so; with what? Or do we just let nature take its course for a while?” Walled garden The Rhyd-y-Meirch flows on into the Upper Pond, then splits in two, with one part following the stream’s original course along the eastern edge of the garden and the other flowing over a textured cascade into the Lower Pond, curved to complete the wall of the Round Garden, rather like a watery ha-ha. The border tracing the curve is planted with a necklace of golden oat grass, Stipa gigantea; their tall, dancing awns glittering gold in the low September sun.

This rare circular walled garden, with an earlier dovecote incorporated into its structure, would have provided a sheltered environment for growing tender plants or vegetables and fruit for the house. Circa 1829, a 2-acre walled garden was built for that purpose further from the house, which boasted the services of 22 gardeners. Together with squabs from the dovecote and fish from stew ponds, the household must have been largely self-sufficient in the mid 19th century. When Elizabeth and Ross moved to Llanover in 1999 with their three young children, Elizabeth felt ill-prepared to take the garden on. “Time I spent working with a couple of local garden designers did help though, and plants are very forgiving,” she says. “If you don’t get something in the right place first time because of ignorance or lack of time, you can then do your research and move it to a more suitable spot.”

The Round Garden was full of ground elder, bindweed and little else. “I just covered the borders with black plastic and didn’t look at it for two years. But after a while, I could see that rejuvenating the herbaceous side of the garden was the way I could make my mark on it, as my father had planted so many trees and shrubs, but few herbaceous plants.” The curving wall of the Round Garden now provides a backdrop for two sensational mixed borders: one 98ft (30m) long, the other 65ft (20m), and both 18ft (5.5m) deep. They were designed in 2009 by Mary Payne, in response to a brief that asked for “maximum effect for minimum effort”.

Her plan of bold blocks of grasses and late flowering herbaceous perennials has been adapted and developed over subsequent years by Elizabeth and her former head gardener, Peter Hall, who worked at Llanover until last year. “Peter was a huge influence on the garden,” says Elizabeth. “I learned so much from him, including tricks of the trade that have improved our presentation. Together we made the display last longer into the autumn by adding dahlias, cannas and ricinus, and we made it hotter by planting more oranges and reds.”

Nowadays, these stupendous borders are full of colour until the first frost strikes, featuring salvias, such as deep purple ‘Amistad’ and the rarely seen pale blue ‘Argentina Skies’; dahlias such as ‘Moonfire’, with yellow and red flowers above bronze foliage, and velvety, dark red ‘Karma Choc’; and those stalwarts of the late border Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’ and luminous, bluish-lavender Aster x frikartii ‘Mönch’. This multitude of flowering perennials is balanced by the foliage of grasses, ranging from tall, refined Cortaderia richardii to low, ground-hugging Hakonechloa macra ‘Aureola’, striped yellow and green. The new head gardener is Nick Carnell, and he enjoyed his first autumn at Llanover last year.

“The light in this part of the world is very special, and it showed the Liquidambar styraciflua ‘Lane Roberts’ off to great advantage as the autumn colour started to show,” he says. “One of my new favourite trees must be the Stewartia monadelpha in the Lower Arboretum, with its beautiful peeling bark and leaves that turn red in autumn. It also has white, camellia-like flowers in early summer, which the bees seem to love.” Family tradition As it leaves the Round Garden through an archway and beneath a simple stone footbridge, the Rhyd-y-Meirch becomes ‘canalised’; contained by a stone-lined channel as it travels across the wide lawns that surround the house.

On its north-east side, a ha-ha gives the impression that the garden extends seamlessly into the surrounding parkland. Unsurprisingly, there are fine trees everywhere, from the London planes that Benjamin Waddington planted to the many hundreds planted by Elizabeth’s father, Robin Herbert, who was president of the Royal Horticultural Society from 1984 to 1994. Robin travelled widely, bringing back many new plants for the garden, including oaks from Mexico, embothriums from Chile and eucalyptus from Australia. Elizabeth and Ross have continued the family tradition of tree planting, focusing on the parkland around the garden and choosing varieties for their appearance at a distance, as well as wind tolerance, because trees are more exposed out in the park than in the shelter of the garden.

Choices include liquidambars; sweet gum trees from North America, with bold, maple-like leaves and spectacular autumn colour; the tulip tree, Liriodendron tulipifera, which goes a deep butter-yellow in autumn; and Golden Scots pines, Pinus sylvestris Aurea Group, with needles turning golden yellow in winter. “We have recently begun to lift the crowns of trees too, to show their ankles,” says Elizabeth. “That way, you get a sense of transparency beneath them. We were inspired by seeing how the Japanese shape their trees on a trip there.” As the garden tapers away from the house, the Lower Arboretum extends to the east, and the two strands of the Rhyd-y-Meirch join up again, flowing gently through a host of interesting trees and shrubs. These include some renowned for their autumn colour: the low, spreading form of the winged spindle, or burning bush, Euonymus alatus ‘Compactus’, blazing pillar-box red, while a majestic Persian ironwood, Parrotia persica, begins to glow orange and yellow.

The leaves of some herbaceous plants can colour up for autumn too, including some that love their feet in the water. Darmera peltata, the umbrella plant, emerges from the stream in the Lower Arboretum beside a bridge; its round leaves on long stalks turning purplish, then beetroot red. Another highlight here is a crimson glory vine, Vitis coignetiae, festooned, bunting-like, over a yew; its large, puckered leaves turning orange and scarlet. Changing soil Beyond the Lower Arboretum is the Victorian kitchen garden, now leased to a young couple who grow vegetables, and beyond that, at the very end of the garden, is an overgrown area that Elizabeth and Ross have only just started to develop: the final piece of the garden’s jigsaw. “We’ve been taking out lots of laurel down there and will probably plant rhododendrons because the soil is acidic,” says Elizabeth.

“It will complete the garden, and although it will mean more maintenance, I think the trees there deserve better.” There are pockets of very acidic soil at Llanover, meaning that Elizabeth can plant shrubs and trees that need it, such as rhododendrons, azaleas and camellias, by using a pH meter to check where the soil is suitable. “Our soil is a glacial till that’s free-draining and easy to work. In a lot of areas, the pH is neutral, so it’s important to check before planting.” Elizabeth sums up autumn’s melancholy-tinged beauty perfectly. “September means a golden glow to me. There’s a sense of calm that comes as the season eases to an end. Days are shortening, and you really savour everything before it’s gone. When I look out at the garden, I see commitment and continuity and think how short my time here is in the overall scheme of things.”