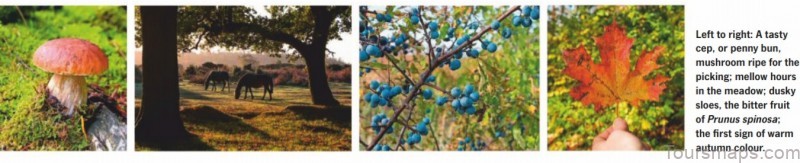

Sarah Ryan discovers treasures on the woodland floor as the season slowly moves into autumn.

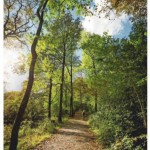

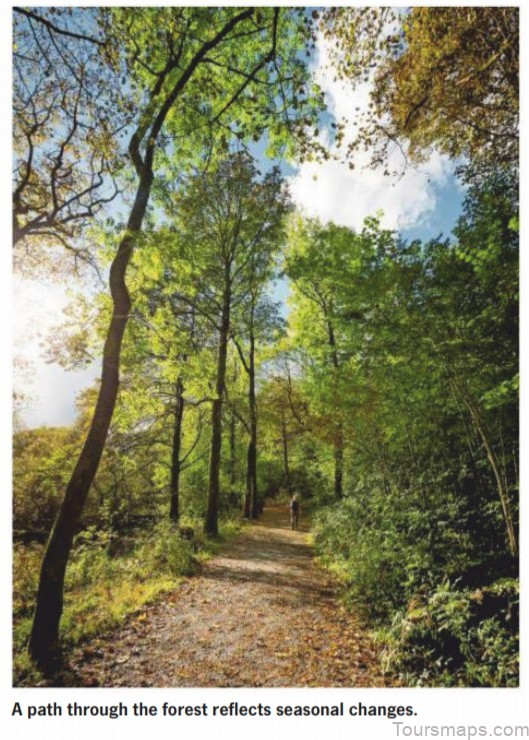

THE DIRT PATH is scattered with leaves, and shallow puddles shine in the low, afternoon sunlight. After a few minutes, I veer off the main track and into the trees, where generations of leaves lie thick and brown. As I step off the path, the dull, regular thud of my footsteps turns to a softer scuffling, with the occasional abrupt crack of a twig. It is September: a time of change and gathering. The year is turning from the green seasons of growing up and bursting out to the rich, damp season of gathering in and settling down. But there is still much to do. There are fruits to plump, leaves to change colour, seeds to harden and cast off.

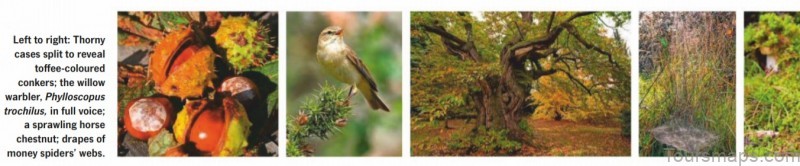

There are nuts to be gorged on and, when the squirrel’s belly is full, more to be buried in earth and leaf mulch. There are flocks of birds to form, miles to be flown and, for some solitary juveniles, the first mysterious, long journey south to be worked out; the bird’s body somehow knowing and finding its way. The breeding season has ended, and the work now is that of preparation and survival. The swallows gather on their adopted meeting point: the telephone wires.

Some restless individuals dash repeatedly up and away; calling to each other in a ribbity chatter. The cuckoo has already gone; swifts, nightingales and willow warblers not far behind.

Map of Scotland – Visit Scotland in Autumn Photo Gallery

Enchanting finds

Under one tree, an old, ridged horse chestnut, with a trunk at least twice as broad as my arm’s reach, is a glossy red-brown nut with a creamy round belly. The conker is lying just a few inches away from its spiky casing; pale green and smoothly soft inside. Further on, I spot a feather: grey-brown on one vane, with just the slightest shadow of a stripe, and almost white down the other, where the stripes are darker and more visible. I pick it up and stroke the ragged edges; smoothing them out and untangling the barbs so that the stripes run in perfect patterns. When I let it go, it spirals to the ground. At ankle height, strung between pieces of vegetation on almost invisible filaments, is a meshy spider web. The delicate net has caught a universe of raindrops.

This kind of web, a sheet web, is woven by a very small spider from the family Linyphiidae, more commonly known as money spiders, which wait below for their prey to fall into the hammock. In the dewy mornings of autumn, they hang silver all over lawns and bushes. Finding each of these feels like unearthing a small treasure. I am keeping an eye out for more edible finds too, especially the round brown cap of a penny bun mushroom, Boletus edulis; so called because it looks exactly like a toasted bun; or perhaps the inedible, magical fly agaric, Amanita muscaria, which springs right out of a fairy tale and up through the woodland floor. I duck out of the woods on the way back and rejoin the path, passing a blackthorn, with its misty blue sloes and a hawthorn, with clusters of little red berries.

Changing palette

The path on the way back is scattered with willow leaves: long, yellow and green lances. Among them, one other leaf stands out. I bend to pick it up, and twirl the stem between my fingers. It is a maple of some kind: palmately lobed, dry and curling at the edges, but vivid with colour. On first glance, it is red, but examining it more closely, I see patches of burgundy, butter yellow, spring green, rusting brown at the tips, and vividly, appropriately, scarlet veins, all artfully splotched. Most of the leaves on the trees are still green, although they are a darker, dustier, more mature shade, without that brightness of striving youth. Over the next few weeks, more will turn. This one red leaf is just the beginning.

Table of Contents