Glistening and violet-crowned, the subject of so many songs, protectress of all Greece – famous Athens with your divine acropolis.

Gods of Olympus, come here to dance! Grant us sublime grace as you come here to the city’s sacred heart, so heavy with the scent of incense, the path which leads here so well-trodden! Come to this sacred land of Athens with its famous market place so elegantly built! And listen warmly to our songs of garlands twined with violets plucked in the dew of spring.

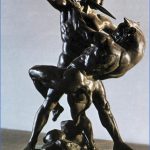

Possibly once holding a winged Victory in its outstretched hand, this bronze statue found at Piraeus in 1959 shows Athene as warrior and protector of her city (c. 360-340 BC).

Come early to the Acropolis before the crowds and heat, and you will be richly rewarded. Enveloped in the golden glow of early morning, the great sanctuary stands empty, the long shadows of the Parthenon’s tall columns rippling across the polished, gleaming rock, while on the Erechtheum’s porch casts of Caryatids gaze with sightless eyes, their faces ready to receive the sun’s warm rays.

Walk the perimeter, look down and you can see (amid the concrete eczema of modern architecture, which chokes the once farm-studded plains of Attica) the Agora, the ancient market place, where the Temple of Hephaestus luxuriates on a low wooded knoll surrounded by pink-flowering oleander; and there the cone of Mount Lycabettus; the ridge of Mount Pentellicon, where marble for the Parthenon was hewn; and the Hymettus range, where bee-hives still produce fine honey. Look south beyond the Theatre of Dionysus and the Muses’ Hill, and out across the sea, where great ships ride at anchor, past the shadowed hump of Aegina to where the mountains of the Peloponnese appear like phantoms in the early haze. Here on the Acropolis it is easy to imagine you are standing at the hub of a great wheel, whose rim embraces the mountains and the farmland and the sea. It is a place of harmony, a place of power. No wonder that gods fought so fanatically to own it.

The Birth of Athene

Athens was named from its patron goddess, Zeus’ virgin daughter, Athene (though the Libyans, who said that she had sea-blue eyes, claimed her father was Poseidon). Her mother was Metis (‘Cleverness’), who at first evaded Zeus by shape-shifting. But not for long. When Metis fell pregnant, Gaia, goddess of the earth, prophesied that the child would be a girl but, if Metis bore Zeus a son, the boy would defeat his father. Keen to cling on to power, Zeus followed his father Cronus’ example and swallowed Metis whole.

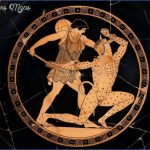

Soon Zeus suffered debilitating headaches. At last the pressure on his skull became unbearable. By Lake Triton’s shores in Libya he bellowed in pain so loudly that he was heard on Mount Olympus. The gods came running, but only Hermes knew what to do. He advised Hephaestus to take his axe to Zeus’ head. The blade crashed down; the skull cracked open – and out leapt Athene, fully grown, armoured and armed, and wearing the aegis, a magic snake-fringed goatskin, which protected her and sowed terror in her enemies. (Others said the aegis was the flayed skin of one of Athene’s goatish enemies, either the Titan Aex or the Giant Pallas, from whom she derived one of her epithets.) Metis, whom Hesiod calls ‘cleverer than any god or mortal man’, remained in Zeus’ belly, where she regularly fed him good advice.

Athens: Prize of Athene, Kingdom of Theseus Photo Gallery

The Goddess Athene

The Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite summarizes ‘clear-eyed’ Athene’s character and attributes:

She takes no pleasure in the deeds of golden Aphrodite, but rather she delights in war and in the deeds of Ares – combat and battle – and the intricacies of fine craftsmanship. She first taught the mortal craftsmen of the earth to make war chariots of bronze. And she taught soft-skinned maidens in their halls and set the understanding of fine arts in every mind.

At first this polarity of interests – war and domestic harmony – seems hard to reconcile. However (unlike Ares), Athene took no pleasure in conflict in itself. Rather, in her capacity as Protectress of the City (Athene Polias), a role she enjoyed throughout the Greek world, she was more than willing to resort to combat when the need arose. Then she would lead the charge with merciless ferocity, as another epithet, ‘Promachus’ (‘Front-Line Fighter’), attests, while her success in battle is reflected in her title Nike (‘Victory’).

Within the well-protected city, Athene presided over the complex craftsmanship of men and domestic skills, such as weaving, associated with women. But when the mortal Arachne was heard boasting that she was a better weaver than the goddess, Athene disguised herself and challenged her to a contest. Arachne’s work was delicately beautiful. The goddess was impressed – until the girl insisted that her skill owed nothing to divine inspiration. Athene destroyed the tapestry in fury, revealed her true identity, caused the terrified Arachne to hang herself and turned the suspended victim into a spider, whose weaving remains breathtaking to this day.

As the child of Metis, Athene was also the grey-eyed (‘glaukopis’) goddess of wisdom, whose avatar was the owl (‘glaux’ in Greek). The bird appeared on Athens’ coinage, often accompanied by a sprig of olive. For it was thanks to the olive tree that Athens belonged to Athene.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Theseus & Peirithous

- The Voyage of the Argo Begins

- Minos, his Loves & his Family

- The Centaurs

- Athens in History & Today