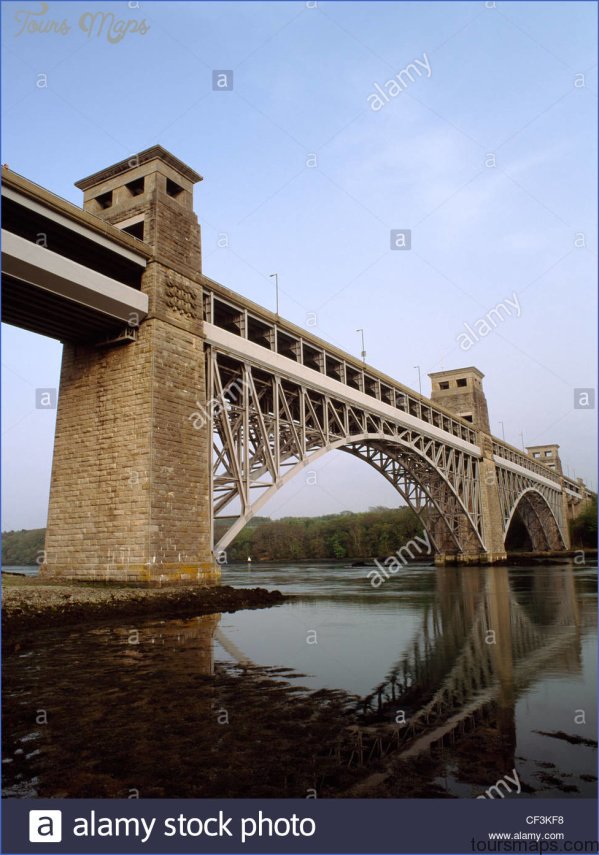

BRITANNIA BRIDGE MAP

Crossing Menai Strait, Anglesey, Wales Designer/Engineer Robert Stephenson Completed 1850

Length Center spans 459 feet (140 meters); end spans 230 feet (70 meters) Materials Wrought iron, limestone Type Iron girder

Stephenson’s use of wrought iron revolutionized nineteenth-century building methods.

In 1838, twelve years after Thomas Telford erected his revolutionary suspension bridge over the Menai Strait in Wales, Robert Stephenson (1803-1859) designed a second Menai crossing. Stephenson, the son of George Stephenson, “the Father of the Railways,” was commissioned to build a bridge exclusively for rail traffic one mile west of Telford’s. Because Stephenson had to span the strait without impeding the passage of ships, an arched bridgewhich would have required a temporary support in the middle of the narrowswas not an option.

With William Fairbairn (1789-1874), a pioneering metallurgist, engineer, and shipbuilder, Stephenson experimented with iron, a synthetic material. Serendipitously, the Prince of Wales, a wrought-iron steamship, accidentally was suspended in air during its launch without damaging the hull. This mishap encouraged their novel plan to span the strait with a tubular bridge of riveted wrought iron. Stephenson’s confidence in this untried technology is clear when one considers that in 1847, while the Britannia was under way, his Dee Bridge (here) collapsed and killed five people, an accident for which he as the engineer-in-chief took responsibility. Despite this setback, the pair moved forward. Their daring yielded a milestone structure that led to the development of box girders and introduced wrought iron, a material that would revolutionize building in the nineteenth century. The tubes filled my head. I went to bed with them and I got up with them.

BRITANNIA BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

The bridge would consist of two independent box tunnels, or tubes, set side by side with a total length of 1,511 feet (461 meters), supported by three monumental limestone towers. The central tower, 221 feet (67 meters) high, was anchored on Britannia Rock, a small midstream island from which the bridge derives its name. Initially, the rectangular tubes were to be supported by chains suspended from the towers, but Fairbairn realized that if the tubes were reinforced with stiffeners they could support their own weight without chains. To protect the iron tubes from the weather, a wooden roof covered their length.

Stephenson laid the first tower stone on September 21, 1846. When the first of Britannia’s tubes were floated into position in 1849, two titans of structural wrought iron, Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) and Joseph Locke (18051860), stood by Stephenson’s side. The first train ran through the pioneering tube on March 18, 1850; the second track opened later that year in October. All three men would die young and within a year of each other, bringing a momentous era of Victorian engineering to an abrupt end.

The greatest obstacle was raising the 1,830-ton (1,660-tonne) central sections.

Stephenson solved this by floating the girders on pontoonsthis time the strait’s extreme tides were an allyand lifting them up the piers with hydraulic lifts.

The bridge was stable, withstanding the loads that rumbled through its length for more than a century. In the end, two boys caused its demise. On May 23, 1970, while looking for a bat roost, the boys climbed atop the bridge’s wooden roof, and dropped a flare when they left. The roof and then the entire bridge caught fire, damaging the tubes beyond repair. The bridge was rebuilt using arches ironically, given Stephenson’s original parametersreopening in 1972, and eight years later a concrete roadway was added as well.

Four massive stone lions, two at each approach, are 25 feet (7.6 meters) long and 12 feet (3.7 meters) high. An equally impressive figure of Britannia was planned for the center tower, but the cost proved prohibitive.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Doncaster, United Kingdom with this detailed map

- Explore Arroyito, Argentina with this Detailed Map

- Explore Belin, Romania with this detailed map

- Explore Almudévar, Spain with this detailed map

- Explore Aguarón, Spain with this detailed map