The city gates stayed closed for two days, the Post Lanzhou Map Tourist Attractions Office van didn’t arrive in time and was locked out. The southern Shansi army seem courteous Lanzhou Map Tourist Attractions , but we stay alert for outbreaks of rioting; our valuables have gone into storage, the cook can’t find fish for sale, and there are some shortages; the daily delivery of ice has been late. [Ice was cut off lakes and canals in winter and packed under earth mounds, in storage for selling in summer. Their winter coal was delivered by camels that had walked from Manchuria.] Tennis and polo have proceeded without interruption. Though rickshaws and cars travelling after 0 p.

Introduction

The Transient City: the city as urbaness’ looks to China’s rapid urbanization and consciousness change in the twenty-first century to seek greater understanding of re-imagining of the city and self in the twenty-first urban century. The discussion applies a re-interpretation of Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis’ (1985, with Regulier, and 2004) to a study of art practice emerging out of the contemporary Chinese experience. It can be observed that urban consciousness, that is the understanding of oneself as urban, is defined increasingly by what Lefebvre called arrhythmia or collision between or amongst two or more rhythms. What has changed is that this now takes place within accelerated transience. In addition, a growing love of transience or what is described here as transphilia (McCormick 2009), as well as a re-assessment of exacerbated difference (Koolhaas 2001) can be observed. The Chinese urban experience has led to an art practice that constructs spaces for possibilities to facilitate understanding of shifts in urban consciousness. The artistic practice of Ai Weiwei and the curatorial practice of Hou Hanru will be discussed for their ways of reflecting, creating and clarifying a consciousness shift that is moving towards urbaness as an understanding of the city as an increasingly connected urban mind space. Although their methodologies differ, the observation and analysis of Hou’s and Ai’s modes of practice provide signposts that assist in understanding urbaness as a category of thought not experienced in earlier urban scenarios. Signposts, while not definitive in their value, have the capacity to reveal challenges to current paradigms or modes of accepted ways of thinking or being, parallel understandings, moments of backlash and possible future directions. Henri Lefebvre observed the beginnings of change in urban consciousness in the twentieth century. Later, Hou Hanru (1991, 2002) coined the term mid-ground’ to describe the twenty-first-century transitionary urban phase. The term still holds true today as the shift towards an urban world continues. The chapter begins by considering an earlier conceptualization of the urban, in the city of Beijing during the Ming Dynasty, and finishes by drawing a reinterpretation of Lefebvre’s arrythmia together with the practice of Ai Weiwei and Hou Hanru to decipher aspects of the contemporary re-imagining of the city as urbaness.

The City and China: Ideas in flux

One wonders what the Ming Dynasty Yongle Emperor would have thought of the twenty-first-century urban world. In the fifteenth century the Emperor moved China’s capital to Beijing and built the Forbidden City as its centrepiece, reflecting the meaning of the word China’ or zhongguo as Empire of the Centre’. Although the emperor had sent out flotillas of ships to explore the world outside this perceived centre, could he have imagined how the city would be re-imagined through the ubiquitous contact of thousands of foreigners’ crossing the Forbidden City’s borders? Fast forwarding to the twenty-first century, could he have imagined how China’s boundaries would become increasingly porous in an urban world with a Chinese population of some 1.3 billion and a Bejing city of more than 30 million? One wonders too what twentieth-century Mao Zedong might have thought about a shift in urban consciousness that now displays very different Shades of Mao’ (Barme 1996) as urbanites walk the streets of cities across the world in designer Mao jackets sporting Mao watches bought on the Shanghai Bund. Then there are Internet and mobile users who slip past the Golden Shield that is the great firewall of China. Mao’s emperor-like portrait still hangs above the Gate of Heavenly Peace in Tiananmen Square but, nearby the square today, one can also see the floating titanium and glass egg-like shape of the National Theatre by French architect, Paul Andreu. A myriad of such buildings by inter-global architects define the new urban China over which Premier Wen Jiabao presided. The city of Beijing was evidence of Yongle’s and China’s centrality and power that was also true in many ways for Rural Mao’ (Wasserstrom 2006: 19) as he re-imagined Beijing in his own image. The notion of the city and self are constantly in flux and both are once more in the midst of being reimagined in ways not formerly experienced within China and beyond. In ways that are very different from both the Yongle Emperor’s and Mao Zedong’s urban imaginations, China remains central to understanding the re-imagining of the twenty-first-century concept of city and its role in reviewing understanding of the self as an urban entity.

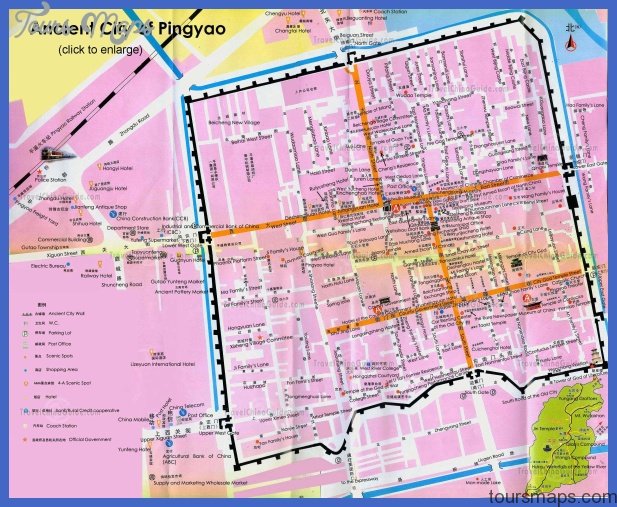

Lanzhou Map Tourist Attractions Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World