The experience of Spaniards in colonial Florida was one of isolation, raids by rival European corsairs and freebooters, tense relations with nomadic Indian groups, and poor funding from the Crown. Although the Crown saw Florida as important strategically, it did not invest heavily in fortifications or in the budgets of the presidios. Instead, these presidios were often marginal places where criminals served their sentences.8 By 1600 St. Augustine was the only Spanish fortification in 600 miles of coastline. In the 1610s, epidemic disease dramatically reduced Indian populations, and labor shortages were common because the Spanish had demanded a kind of levy draft labor system from their Indian subjects. In 1622 a massive hurricane devastated trade. The year of 1628 was a low point for Florida. For the first and only time in its history, an entire Spanish silver fleet was captured, by Dutch naval officer and privateer Piet Heyn, off the coast of Cuba. Subsidies for the Florida presidio and mission systems were devastated.

In the wake of these events, a new push to expand Spanish presence came from governors Luis de Rojas y Borja and Luis de Horruytiner. What became known as Middle Florida (the area in the panhandle around Tallahassee) was settled, and Franciscan missionaries began to set up small missions. Tallahassee and the Apalachee area would provide food and harbor for Spanish ships fleeing corsairs in the Gulf of Mexico. In theory the expansion was a good idea, but like much of the history of early Florida, the Spanish were harassed by raids and unpredictable weather. The Apalachee rebelled against Spanish rule in 1647, and an internal war between Christianized and non-Christianized tribes broke out. In 1668 St. Augustine was sacked by English corsair Robert Searles. In 1670 English settlers from Barbados founded Charleston. The Spanish Crown responded to these events with increased investment in Florida. In the 1670s the building of the massive stone Castillo de San Marcos was begun in St. Augustine.

Despite the efforts of the Crown, Spanish Florida remained a place renowned for seemingly constant war and raiding. In fact the Spanish population of Florida may have fallen below 1,000 by the end of the War of Spanish Succession in 1713.9 Even the missionaries, who were famed for their intrepid nature and willingness to live in the most extreme circumstances, fared poorly in Florida. By 1759, it is reported, there were less than 10 Franciscan priests in all of Florida. South of St. Augustine there was virtually no Spanish presence at all on the Atlantic coast.

In 1683, amid the various explorations and expansions into Middle Florida, Pensacola Bay was scouted by the Spanish. It was settled, and some argued that it should replace St. Augustine as the capital of Spanish Florida a suggestion rejected by Charles II. As in the rest of Florida’s early history (or modern history, for that matter), criminals settled Pensacola. Many of the settlers sent to work in the presidio had come from jails in Mexico or were press-ganged into service from the poorer sections of Mexico City and Veracruz. The Spanish priests who went to Pensacola often complained bitterly of the low moral standing of the presidio defenders, who had little incentive to defend imperial ambitions. Likewise, despite the efforts of the Crown to the contrary, Pensacola proved an excellent place for contraband international trade with the French of Louisiana and Mobile. By 1763 Pensacola had only barely survived after decades of raids, smuggling, disease, and neglect this despite the fact that the Crown had sunk more than 4.5 million pesos into the endeavor. When Pensacola, along with the rest of Florida, went to the English, there were only a few hundred Spaniards there, compared with perhaps over 2,000 in St. Augus-tine.10

In 1763 Florida was ceded by the Spanish Crown to England in exchange for Havana, which the English had taken during the various imperial wars known as the French and Indian (or Seven Years’) War. Spain saw Florida as increasingly less important, but more significantly it viewed Havana as much more important. Cuba was home to a burgeoning sugar plantation economy, and by 1763 Cuba had supplanted Brazil as one of the world’s major sugar producers. Cuban plantation owners had adopted new technologies in production developed in Barbados and the island was fast emerging as an important piece in Spain’s international economy to say nothing of the Caribbean. Florida, on the other hand, produced virtually nothing. In the end this worked well for Spain, because Cuba emerged over the next three decades to become the world’s major sugar producer, rising in importance after the Haitian Revolution, which ousted French slave owners.

In all, it appeared that Florida was a kind of lost land, a marshy bog forgotten by history and left out of the important shipping lanes between Panama, Veracruz, Havana, and Seville. How ironic this state of affairs seems now, when Miami is perched as one of the Caribbean basin’s most important Latin cities, and when the relationship between Florida and Cuba has never been stronger.

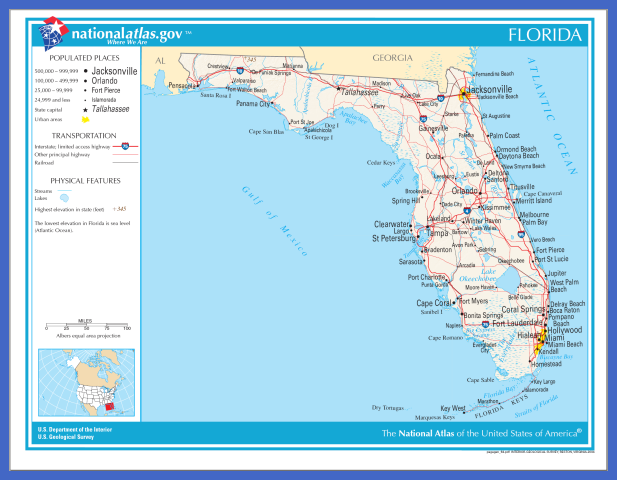

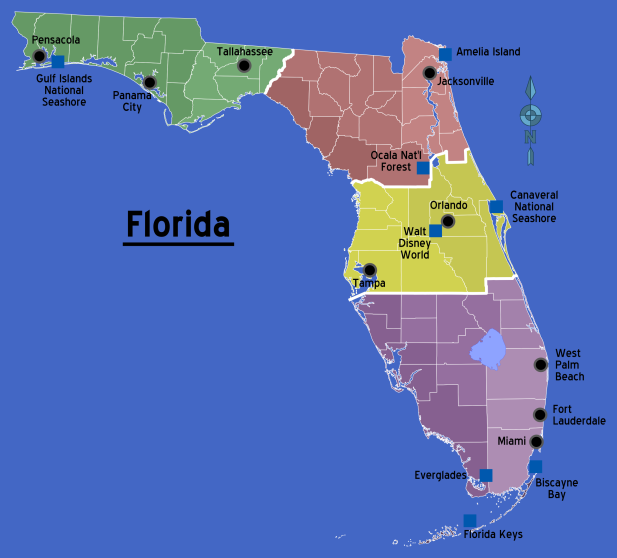

Map of Florida Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Pulau Sebang Malaysia with this Detailed Map

- Explore Southgate, Michigan with this detailed map

- Explore Les Accates, France with this Detailed Map

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map

- Explore Gumdag, Turkmenistan with this detailed map