You get a hint of what delights you might see long before you reach Schynige Platte on the little cog wheel railway that takes you up there from the village of Wilderswil, a suburb of Interlaken down in the valley way below. Opened in 1893, this little railway was electrified in 1914 and it takes just under an hour to get its passengers from 600 m at Wilderswil to nearly 2,000 m at the Schynige Platte station where the views are framed by a trio of famous Alpine peaks – the Jungfrau, Monch and Eiger, snow and ice-covered monoliths towering nearby. It is a typical piece of Swiss mountain engineering in which getting to some almost inaccessible spot is simply a minor problem waiting to be overcome.

Today, the Schynige Platte railway is of historic interest in itself; it still operates one of its original steam locomotives, together with the four electric locomotives built for the line’s electrification. Parts of the climb are at a 1 in 4 pitch and there’s a passing place half way up where the down trains sneak past the up trains. From the windows in the two coaches on our train with the square-set, cream and red painted electric engine named Fluhbluhme pushing from behind, we jogged and rattled along the narrow gauge through shaded spruce forest before we encountered the first alpine meadows above.

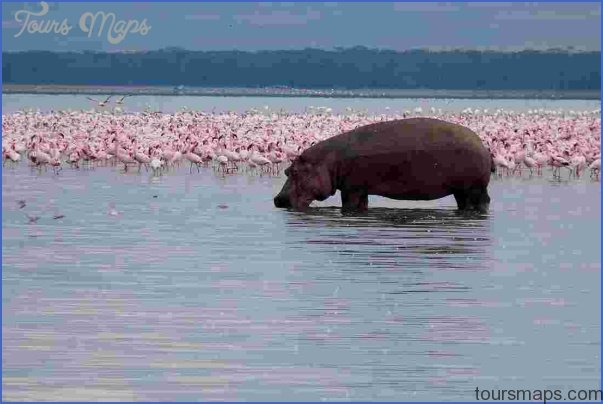

National Wildlife Travel Photo Gallery

And Fluhbluhme turned out to be a rather prescient engine; dotted about in some of the shadier spots between small rocks on the route up were its namesake: the remains of what had been vibrant yellow flowers on tall stems above somewhat fleshy blue-green leaves; these were the remains of Mountain Cowslip, or fluhbluhme. They would have been in full flower maybe a month earlier because this is a spring-flowering beauty. Spring here means June; at this altitude the snow hasn’t melted fully until then.

Just metres away from the platforms of the Schynige Platte station, the alpine garden of the same name, founded in 1927, would blow the mind of any alpine gardener I have ever met. It is loaded with nearly 700 different alpines; from tiny saxifrages to alpine ferns and large shrubs, all of them native to the Swiss Alps and growing in natural locations. And the labelling would put even the best of Britain’s National Trust gardens to the test. Here, at over 2,000 m with a four-month growing season – June to maybe mid-October – and the rest of the year snow and ice-covered, is one of the highest botanical gardens in the world set in scenery that would be the envy of many a picture postcard.

You can walk up here if you wish – with typical Swiss organisational efficiency the paths through the spruce forests are clearly waymarked but it is hard going and once you get here you are likely to be too exhausted to be looking at flowers. With that old British Rail motto ‘let the train take the strain’, I was glad not to have attempted it. My biggest difficulty after a splendid train journey was where to look first. Surrounded by every colour imaginable dripping over patches of rock and gravel, it proved best to follow the well-marked gravel paths from one re-creation of a botanical habitat to another.

That way I was able to get a picture of the alpine plants typical of snowbeds; plants of calcareous rocks like the little, delicately white-flowered Dangling Cinqufoil; dwarf shrub heaths dominated by the black-berried Crowberry and similar; plants such as the tall, purple/blue-flowered Alpine Sow Thistle found in wet Green Alder scrub and many more besides. But it proved difficult not to get attracted to the most colourful: the little buttercup-yellow, rather oddly named Orange Poppy lighting up the rock crevices and gravel they thrive in; the foot-high clumps of fragrant, white St Bernard’s Lily like miniature trumpets springing from grey-green grass-like leaves; or the elegant, tall and intensely blue spikes of Alpine Larkspur. I tried not to fall into the trap of overlooking some tiny gems by getting too entranced with the more showy species but it wasn’t easy. The delicate and tiny fronds of the Moonwort fern for example, no more than maybe 7 cm tall, a single frond with pairs of fan-shaped leaflets accompanying a second stem bearing grape-like clusters of spore bodies. It peeped out from amongst a dense cover of grasses, not an obvious plant but a beauty nevertheless and one that I had once found very rarely in one or two damp Welsh meadows back home.

June – as the last snows melt – is the best time for blue and purple Soldanella, its flowers like downward hanging bells and for Crocus, and yellow-centred, white-petalled Pasqueflower. July is maybe the peak time overall at Schynige Platte (depending on season) and I saw an array of colours: grey-white Edelweiss, that symbol of the rugged purity of the High Alps and said to be Hitler’s favourite; Alpenrose, the dwarf, pink/red-flowered azalea that grows like a carpet; the Alpine Poppy, white-flowered with yellow hearts growing here amongst boulders and scree; and the lavender-petalled Alpine Aster, each flower with a vibrant yellow centre. August signals the end of the summer, but it certainly goes out with a bang. Tall, dark pink-purple Martagon

Lilies compete for height with clumps of Yellow Gentian and their layers of showy flowers. More subtle is the small Alpine Toadflax, having bright purple flowers with orange centres, while the tall single white flowers of St Bruno’s Lily are elegant in their simplicity.

But I didn’t want to spend the day in the alpine garden; I headed out amongst the surrounding natural meadows on a waymarked loop towards the moderate peak of the Loucherhorn. This route gave me amazing views north and northwest (way down below) of the twin Thun and Brienz lakes, both shimmering blue, and of the appropriately-named town of Interlaken between them. I made slow progress; out here many of the meadows, the slopes, rock outcrops and screes all around were burgeoning with a profusion of wild plants including very many that I had seen labelled in the garden. At times it seemed as if there was little distinction between the cultivated alpine garden and the natural alpine meadows. The whole place is one of the finest in Western Europe in which to search for alpine plants.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

- Anniston Map

- Wildlife Travel Guide

- Wildlife Travel To Alonissos

- Arabian Safari