All this time I had been pondering my 1960 race across the Atlantic.

Before the start I had known that the rival yachts would never see each other, and I had set myself a target time to race against, thirty days. This was the time I reckoned that a winning yacht of Gipsy Moth’s class should take with a full crew of six, in an RORC race across the Atlantic from east to west. In 1962, for example, there were twelve RORC races in British and French waters. They averaged 250 miles apiece, so that the twelve totalled the same distance as the single-handed race, 3,000 miles. Adding the times taken by the winners of these twelve races for the same size class as Gipsy Moth gave an average speed of 107% miles per day. Allowing for the Gulf Stream’s setting her back 9% miles a day for the first 2,000 miles; I reckoned that 100 miles per day throughout was the equivalent speed, and the best I could hope to do. When I took forty and a half days I was disappointed.

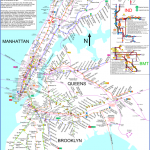

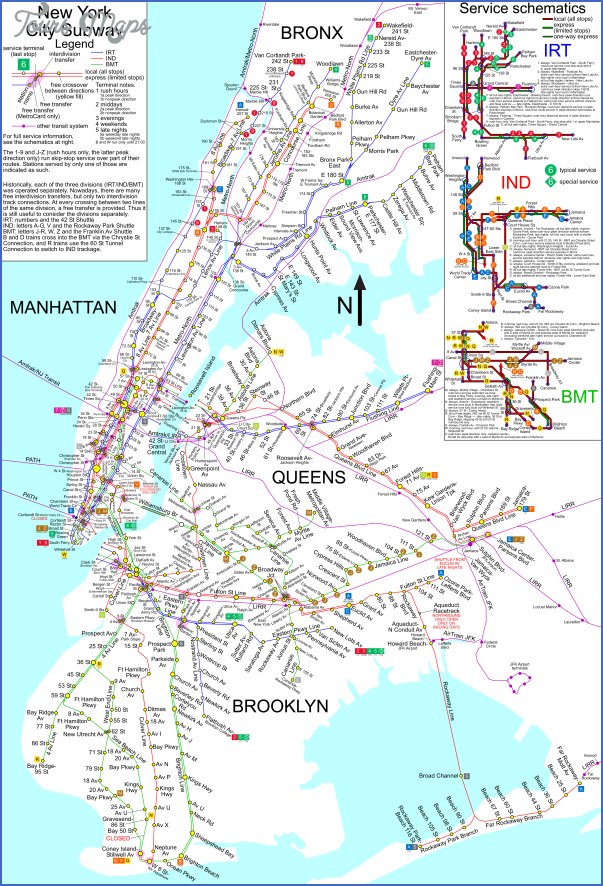

New York Map Detailed Photo Gallery

I thought Gipsy Moth was too big, and her gear too heavy to handle for one man. By the end of the 8,000-mile voyage, I had thought up a number of different ways to make the gear-handling easier, and the yacht faster. I asked John Illingworth if he would redesign the mast and sail plan to my requirements – he is not only one of the most experienced and successful of ocean racers, but also an engineer who probably knows the stresses involved in tough ocean racing better than anyone: during the winter of 1961 a metal mast was built for Gipsy Moth. It was a little shorter, 53 feet instead of 55 feet. Some of the other changes I planned were: a smaller mainsail, which would balance the headsails better; and be easier to handle.

The heavy main boom, which had caused me so much trouble, was cut down from 18 feet to 14 feet, and the lethal runners, which had seemed animated by a mad lust to brain me, were eliminated. The headsails were bigger, to compensate for the smaller mainsail, and the sloop rig was changed to cutter rig.

As soon as all this was under way, I had a strong urge to try out Gipsy Moth in 1962, to see if my ideas were correct. I believe that this is the greatest urge to adventure for a man – to have an idea, an ideal or an ambition, and then to prove, at any cost, that the idea is right, or that the ambition can be fulfilled. At first I thought, ‘What about a sail to the Azores and back?’ Then I remembered our delightful visit to Indian Point, and thought, What fun it would be to nip across the Atlantic to see them again.’ From here the next step was easy: Why not try for a record crossing? Air pilots and racing motorists are always trying for records; why not a sailing yacht for a change?’

My enthusiasm was dampened when I came to consider the cost of the double crossing, together with the cost of all the changes and improvements to Gipsy Moth.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit