North Dakota cultural contributions

As testimony to the Latino history of the state, there are many Spanish place names in North Dakota, including Alamo (poplar, aspen, or wood), Arena (sand), Fonda (inn), Grano (grain), and Loma (hill). Some of these names, such as Flora and Fortuna, may have been taken directly from Latin. Names such as Emerado and Mantador seem to be corrupted Spanish forms of esmerado and matador. The name Medina, Arabic for town, is a common city name in the Spanish world. Juanita is a Spanish surname, and Havana is the English form of the Spanish Habana, the capital of Cuba. The community of Maza was named after Maza Chante, the Sioux chief. Maza itself means metal in Lakota, and Maza Chante means armor. Because the Spanish maza means a club, a hammer, a mace, or a piece of metal, the Lakota maza seems to be a Spanish borrowing.

Latinos, despite their small numbers, have made many contributions to the North Dakotan community, including the Centro Cultural de Fargo-Moorhead which, along with Concordia College, Minnesota State University Moorhead, Mujeres Unidas, and NDSU, organizes celebrations for Hispanic Heritage Month in Fargo-Moorhead.

In business, Latinos have brought several restaurants to the Fargo area, including two Mexican restaurants, Acapulco’s and Juanos. Owned by Mexico City-native

Juan Mondragon, Juanos has turned into a veritable chain. Marla Simon, a seamstress from Mexico City, operates Alterations Sew Special in Fargo, serving customers from across the country, whereas Rodrigo Casarez runs Below Radar, a tattoo and piercing shop in the heart of downtown Fargo. One of the most influential Latinos in the community is Raul Gomez, co-owner, copublisher, and design editor of the High Plains Reader, the first Latino-owned media outlet in North Dakota.

The North Dakotan Latino community has made many contributions to the field of social services. Mujeres Unidas, formed in 1989, is directed by Jill Danielson and codirected by Monica Trevino. The group aims at educating and empowering Latinas, breaking the cycle of racism, poverty, and oppression. In January of 2003 the Moorhead Human Rights Commission recognized the efforts of Mujeres Unidas, granting Human Rights Awards to Hilda Acevedo, Amy Cerna, Bianca Mendez, Belinda Rendon, and Dezi Gonzalez, ages 17 to 21. In 2004 the YMCA named Mujeres Unidas Women of the Year in the category of Organization That Empowers Women. Concerned with domestic violence, Latinos from both North Dakota and Minnesota formed the Hispanic Battered Women’s Program in Moorhead, Minnesota. The Centro Legal, though located on the Minnesota side of the twin cities of Fargo-Moorhead, serves many North Dakotan Latinos.

As has been the case for nearly a century, religious life in the North Dakota Latino community revolves primarily around the efforts of non-Latino members of the Roman Catholic Church. Sister Bernadette Trecker has worked in the Hispanic ministry since the 1960s, and Sister Leona Ulewicz is presently the director of Hispanic Ministries in the diocese of Crookston, and she has an intimate knowledge of the Latino community in the Red River valley. At present, Father Timothy C. Schroeder leads the Migrant Workers Apostolate for the Fargo diocese. He holds masses in Spanish in his parish sixth months out of the year. Latinos have increasingly been assuming positions of leadership, particularly in the Protestant community. Pablo Guajardo, a son of migrant farmers, started a Hispanic ministry in the spring of 1978 or 1979. Besides being an active community leader in Moorhead, Minnesota, for over 30 years, he serves as the pastor of Mision Bautista Buen Pastor, which meets at the Temple Baptist Church in Fargo, North Dakota.

Latino North Dakotans have also been active advocates of cultural diversity, participating in the Cultural Diversity Project, a community-wide collaboration among four cities in two states Fargo and West Fargo in North Dakota, and Moorhead and Dilworth in Minnesota to address immediate community diversity issues while working toward systemic community changes.

Latino culture has also made contributions to the First Nations of North Dakota. Spanish names are common on many reservations. Several indigenous women worked in the defense effort in World War II and married Latino men. Residential schools such as Haskell, Chilocco, and Intermountain brought Native

American students from all over the United States, including Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache Indians, many of whom have Spanish surnames. From the early 1900s to the 1940s many marriages took place between the First Nations of the Southwest and the First Nations of North Dakota, as a result of boarding school acquaintances. The relocation program in the 1950s and 1960s, which took indigenous people from reservations to urban centers such as Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, and Dallas, all resulted in marriages outside of the tribal group. When many of these North Dakotan natives returned to their reservations, they brought their Latino spouses. Latino culture, however, is not particularly prevalent on reservations. This is due in large part to the matriarchal practices of many indigenous societies, in which the cultural and linguistic identity of the Native women prevails over the Latino heritage of the husband.

notes

1. Most early Latino settlers were eventually assimilated in mainstream Anglophone American culture, leaving only a Spanish surname as a hint of their lost Latino heritage. This process was facilitated by the fact that there were very few Latinos in the state, which in turn led Latinos to marry with non-Latinos. The assimilation of Spanish settlers was even easier for those who were fair skinned and because their regional identities prevailed as opposed to a single national identity. Viewing themselves through regional identities such as Basques, Catalans, and Gallegos, Spanish migrants have rarely formed broad inclusive communities with their other countrymen.

2. In response to the growth in the Latino population, some reactionary segments of North Dakotan society turned to the Ku Klux Klan, an anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant organization. Concerned with the growth of the Klan in North Dakota, the state legislature passed a law on January 10, 1923, prohibiting all citizens over the age of 15 from wearing a mask or any other head covering in front of a public building to conceal their identity. As a result of these efforts, the Klan started to decline in the late 1920s, essentially ceasing to exist in Grand Forks by 1929. However, as was common in many parts of the South, Southwest, and Midwest, many businesses and communities in North Dakota continued to post signs stating No dogs or Mexicans well into the 1960s.

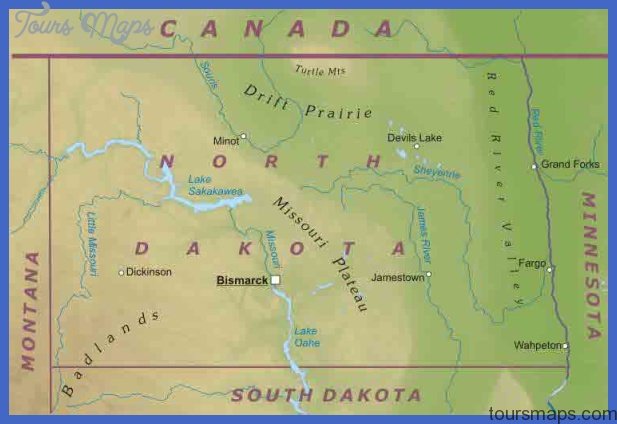

North Dakota Map Tourist Attractions Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Southgate, Michigan with this detailed map

- Explore Les Accates, France with this Detailed Map

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map

- Explore Gumdag, Turkmenistan with this detailed map

- Explore Telfes im Stubai, Austria with this detailed map