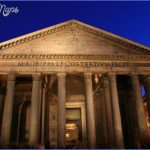

Pantheon c. 110-124 CE TEMPLE ROME, ITALY

ARCHITECT UNKNOWN

The best preserved of all Roman temples is the Pantheon in Rome.

It is famous for its massive entrance portico and colossal circular dome, which was the biggest such structure of its time and is still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world. The Pantheon was built on the site of a temple that had been destroyed in a fire. Historians used to attribute the Pantheon to the emperor Hadrian (reigned 117-138 CE) and his architects. Recent archaeological work shows, however, that some of the bricks used in its construction are from an earlier period, so the work may have begun under the emperor Trajan (reigned 98-117 CE) and been finished under Hadrian.

Most Roman temples were rectangular and surrounded by columns in a similar way to Greek buildings such as the Parthenon (see pp.20-23). The Pantheon is, however, different. Its portico leads to a rectangular vestibule, and beyond this is a rotunda (a circular chamber) perfectly proportioned so that its diameter and height match-both stand at 142/ft (43.4m), which equals 150 Roman feet. The reason for the building’s unusual design is unknown, but the spherical shape may symbolize unity, since the Pantheon was a temple dedicated to all the gods.

Remarkable for its unique proportions and the engineering achievement of its dome, the Pantheon is also unusually well preserved. It became a church in the Christian era, and as a consequence the building was cared for. Features such as the marble cladding of the interior, for example, were not removed and recycled elsewhere, as was the case with most Roman buildings. The Pantheon survived to influence the designers of countless other buildings roofed with domes and fronted by classical porticoes.

ON CONSTRUCTION

The dome of the Pantheon is built of concrete, a material that the Romans used widely, especially for structures such as vaults, domes, and curving walls. The result is one of the most stunning roofs in all ancient architecture, plain and purposeful from the outside and elegant within.

The architect carefully designed the dome so that its shell is thick around the edge and much thinner towards the top the upper part is only about 4ft (1.2m) thick. The builders also made the dome’s structure lighter toward the top by mixing the concrete with tufa and pumice instead of the tufa and brick in the lower part. This ingenious construction reduces the weight of the dome and minimizes the strain on the supporting walls. At the very top is a circular hole, the oculus, which is open to the sky, 1 oome The stepped profile and letting natural light into the heart of the building. oculus are clearly seen from above.

Visual tour

2 CAPITAL Although the capitals of the portico are badly worn, they still bear the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian order, which was invented by the ancient Greeks and imitated by the Romans. This delicate decoration complements the rather severe treatment of the rest of the fagade, providing relief for the eye as well as an elegant termination for the tall granite columns.

1 PORTICO Eight Corinthian columns front the Pantheon’s portico. The shafts of these columns are 39ft (12m) tall, the equivalent of 40 Roman feet. The columns support a simple entablature, above which is the large triangular pediment. This looks very plain now, but would have originally housed some form of sculpture. This may have featured an eagle set inside a wreath and was possibly made of gilded bronze to match the bronze doors below, which survive to this day.

The upper level of the walls helps to buttress the dome, which appears saucer-shaped from the outside although hemispherical within

2 RELIEVING ARCHES The walls of the Pantheon’s rotunda are made of a combination of concrete and brick. Although they form a very simple circular shape, these walls are built in a complex way on very deep foundations in order to cope with the stresses and strains generated by the enormous dome above. One feature that strengthens the wall is the series of large, brick relieving arches that can be seen at different levels around the building. The upper level of the wall, where these arches are most clearly visible, conceals and strengthens the lower part of the Pantheon’s dome.

The floor is covered in slabs of granite, marble, and porphyry

The temple was originally raised above the surrounding ground and could be reached via a flight of steps

The oculus is 27ft (8.2m) across and lights the interior

The dome is thinner toward the top to reduce the weight

4 WALL NICHES AND ALTAR Eight niches, one of which forms the entrance, surround the rotunda. A pair of marble Corinthian columns flanks each one. Originally, the niches probably housed statues of the Roman gods. Later, they were transformed into Christian altars.

ON DETAIL

The Romans were famous for their beautiful inscriptions in capitals, the styles of which still influence typographers and stonemasons. These inscriptions are outstanding for the subtle variations in the widths of their strokes, making them visually attractive and easy to read. Inscriptions in Roman capitals appear on gravestones, monuments, triumphal arches, and civic buildings. The Pantheon inscription, which runs along the entablature of the portico, commemorates the previous temple on the site, erected by the general and politician Agrippa in the 1st century bce. Hadrian and Trajan saw their work as rebuilding the temple, so did not claim the building as their own.

Portico inscription

In inscriptions such as the one commemorating Marcus Agrippa on the Pantheon, the Romans perfected the capital letters that we still use today.

IN CONTEXT

The Romans’ use of concrete helped them create all kinds of structures, not only large domes such as the one roofing the Pantheon, but also arches and vaulted ceilings. A structure they often used in large buildings was the barrel vault, a vault with a semicircular cross section. This kind of ceiling proved effective in large public or imperial buildings, where the architect wanted to create a sense of grandeur. Concrete vaults were especially useful for bathhouses, where a wood-framed roof would have been badly affected by the damp atmosphere.

Baths of Caracalla

The baths built in the 3rd century ce by the emperor Caracalla had many domed and barrel-vaulted ceilings.

PANTHEON ITALY Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit

- Coolest Countries in the World to Visit

- Travel to Santorini, Greece

- Map of Barbados – Holiday in Barbados