The Progressive Era and the Mexican Revolution

The Progressive Era, the first two decades of the twentieth century, was marked by an acceleration of economic expansion. By 1920 the populations of many major cities numbered more than 50,000, with almost a third of Texas’s population living in urban areas. In the lower Rio Grande valley, the introduction of large-scale irrigation attracted thousands of white settlers into the state’s southern region. Texas’s overall population increased from 3,048,710 in 1900 to 4,663,228 by 1920. By 1919 the value of cotton and livestock production led to Texas’s increase in national power and influence.

For all the prosperity witnessed during this time, the positive impact on Mexican American lives was marginal. With their numbers soaring to 250,000 by 1920, Tejanos still endured minimal political representation, except in a few small towns and San Antonio. This was in part attributable to the presence of a system known as boss rule, whereby local bosses, usually Anglo-American, maintained control over Tejano votes. Particularly palpable in south Texas by the end of the

nineteenth century, the bosses’ control of the state protected Anglo interests and used the threat of the Texas Rangers to intimidate Mexican American citizens. The bosses helped large Anglo ranchers steal Tejano land while ensuring that Tejanos voted in the right way. While they also fulfilled the role of patron to Tejanos distributing money to carry them through hard times and paying for weddings, funerals, and festivals this was with the understanding that Tejanos would acquiesce to manipulation.

Mexican American votes were also impacted by poll taxes instigated after the Civil War. Although initiated to disenfranchise African Americans and some poor whites, these taxes effectively removed most Mexican Americans from the electoral process. This eventually led to the white primary law of 1923.

The most important event to change the course of the Tejano experience in a positive way was the 1910 Mexican Revolution. In 1876, Porfirio Diaz began a four-year term as Mexico’s president. Elected once again in 1884, he removed restrictions for reelection and remained president until 1911. He ruled as a despot, maintaining power through political corruption, through the unbridled use of the military, and through assassination. As it became impossible to criticize the regime inside the country, many liberal intellectuals and journalists fled, some settling in Texas.

Even during the Porfiriato’s early decades, the impact on Tejanos was profound. Mexican journalist Catarino Erasmo Garza settled in Brownsville, where he promoted many of the established sociedades mutualistas; he also helped create these types of organizations in Brownsville, Laredo, and Corpus Christi. In 1887 he helped to publish El Libre Pensador, citing many abuses of power by Diaz and his lackeys. After U.S. authorities confiscated his machinery and imprisoned him for one month, he moved to Corpus Christi, where he renewed his attacks through the newspaper El Comercio Mexicano. This time he attacked not only the Mexican government, but also the Texas Rangers and others who were oppressing Mexican Americans.

Along with many south Texas and northern Mexico sympathizers, Garza plotted Diaz’s overthrow. He had no problems recruiting followers, as Diaz’s abuses were numerous and appalling. During the Garza War (1891 and 1892), Garza and his associates staged three raids in Mexico. These were unsuccessful, as Diaz’s powerful northern forces repelled Garza’s army. In 1892, the U.S. government sent forces to Texas to address the conflict, the violence of which was spilling over the border. Garza left the state.

Opposition to the Diaz regime began in earnest in the twentieth century with the inception of the Mexican Revolution. In the 1910 election, Francisco I. Madero ran against Diaz on a platform of real suffrage and a one-term presidency. Fearing Madero’s growing popularity, Diaz imprisoned him. Out on bail, Madero

fled to San Antonio, where he issued the Plan de San Luis Potosl, a document that was a call to arms against the Diaz political and military machines.

Madero’s cause was greatly aided by brothers Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magon two Mexican journalists who established a newspaper, Regeneration, in San Antonio in 1904. They condemned the Diaz regime, citing many injustices perpetrated by the despot. After being harassed by Mexican and U.S. governmental agents, the brothers fled to St. Louis, where they founded the Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM) and established many chapters in Texas. Tejanos and recently arrived migrants sympathized with the PLM, as the party not only addressed Mexican injustices, but also weighed in on those against Mexican Americans in border states. The progressive PLM included women in their ranks, and many, like Laredo’s Sara Estela Ramirez, worked toward women’s equality. Other Tejanas functioned as speakers organizing rallies and fund-raisers for workers’ causes. By 1911 opposition from both the right and the left and from Mexico and the United States had critically destabilized the PLM.

Regardless of the PLM’s eventual collapse, members and onlookers had learned the importance of political awareness, as well as the power of the pen. Women were particularly inspired, and newspapers like La Mujer Moderna, founded by San Antonio’s Andrea and Teresa Villarreal, and the weekly Voz de la Mujer, published by El Paso’s Isidra T. de Cardenas, offered a feminist perspective on events while underlining labor and the importance of solidarity. In San Antonio, La Prensa, a Spanish-language newspaper, filled the void left by Regeneration in 1913. The paper’s founder, Ignacio E. Lozano, covered events in Mexico while monitoring events impacting Tejanos, including local meeting announcements and news of abuses throughout Texas. By the end of the publication’s first year, readership was around 10,000. During its fifty years of publication, this paper became the most widely distributed voice of the Spanish-speaking populace of Texas, with readers in the United States, Central America, and South America.

Migration numbers escalated as members from Mexico’s upper and lower classes fled Mexico’s destabilized lands. Many migrants integrated and married into the preexisting border populations. To curb the flow of foreigners, the U.S. government instigated the Immigration Act of 1917, requiring an eight-dollar tax per person and the successful completion of a literacy test to gain entrance into the country. Once in, the migrants found that they were not always of the same political bent. Among Mexico’s elite refugees, a war of words, battled out in editorials, ensued between Madero and exiled Diaz supporters. By far, however, the new regime supporters were favored over those of the old.

As the ranks of laborers swelled, workers’ rights occupied a privileged position among Mexican Americans. Although rejected by mainstream white-controlled labor unions and craft guilds, Tejanos formed and joined more open-minded

groups. La Agrupacion Protectora, established in 1911, drew small-farm renters and laborers and saw some success in protecting their members from illegal repossession of their property. Tejanos also joined forces with many socialist affiliates that were gaining in popularity throughout the United States.

The sociedades mutualistas continued with success. One of the largest, the Alianza Hispano-Americana, established in 1894 in Tucson, Arizona, spread to many southwestern states. By 1906 it had Texas affiliates in major cities, and eventually lodges were established in smaller towns as well. Like most mutualis-tas, the organization provided funds for widows and their children and encouraged free speech. Part of the Alianza’s agenda, which favored democratic engagement, extended membership to women in 1913.

An outgrowth of the mutualistas was the female-run Cruz Azul Mexicana. This organization, founded in San Antonio in 1920, was dedicated to the aid of poor families, as well as education. As education reformers, members established a library in San Antonio in 1925. They also helped to fund a public clinic and offered legal assistance to the poor. The Cruz Azul eventually spread to rural towns.

Women were also very important in the promotion of education. In 1911, teacher and journalist Jovita Idar formed the Liga Feminil Mexicanista in Laredo. Most members were working-class women, and their goal was to reform education and promote rights for Texas’s children. With this goal in mind, many educated women opened schools that were free of charge to impoverished children. They also took up collections of clothing and food to be distributed among the poor, holding fund-raisers to pay for the association’s activities.

Reform was not always peaceful; sometimes, frustrated desires for equality manifested themselves in violent uprisings. In 1915 some Tejanos joined in support of the Plan de San Diego, a manifesto created in San Diego, Texas, calling for a separate Mexican American nation. The plan called for the reclamation of lands lost in the 1836 war with Mexico and those lost in the 1848 signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Tejanos, accompanied by some Mexicans from northern Mexico, led raids along the border. The Texas Rangers were called in, and the governor at the time, James E. Ferguson, threatened to send additional forces down to the border region. By November of that year, hostilities had ended.

Mexican Americans occasionally found themselves caught up in mayhem not of their making. Francisco (Pancho) Villa had sided with progressives during the Mexican Revolution, and after Victoriano Huerta usurped Mexico’s presidency, Villa sided with Venustiano Carranza and rallied his forces. After falling out with Carranza, Villa began raiding towns along the Texas-Mexico border. The situation escalated when, in January 1916, Villa murdered sixteen Americans in Mexico, and conflict between Mexican Americans and the white population broke out in El Paso. After Villa attacked Columbus, New Mexico, the United States sent

General John J. Pershing to hunt for him. Further clashes continued for years after 1916, disrupting communal peace along the border.

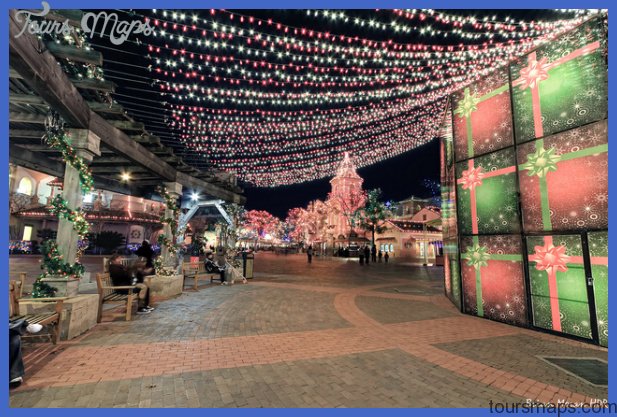

Holiday in Texas Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit

- Coolest Countries in the World to Visit

- Travel to Santorini, Greece

- Map of Barbados – Holiday in Barbados