Viticultural imperatives in cool climates

Too cold can be as troublesome as too hot. Given New Zealand’s cool climate, getting the grapes physiologically ripe with aromas and flavours that express the variety and where it is being grown is the primary viticultural imperative. Viticulturists achieve ripeness by managing the architecture of the vine and level of the crop through pruning and rubbing off unwanted buds and by managing the canopy to maximise photosynthesis. Successfully achieving these objectives assumes that nutrient levels and the moisture regime in the soils and vine are also effectively monitored and managed.

The second imperative is to avoid catastrophic events that drastically reduce yield.

Frost after the leaf buds have burst in spring is the best example. Hail at almost any time in the growing season is another. The vine is especially vulnerable to hail when shoots and leaves are young and when fruit are ripening. In deciding precisely where to plant grapes the probability of such catastrophic events needs to be considered alongside the seasonal temperatures and rainfall conditions that influence the vine’s ability to ripen its fruit.

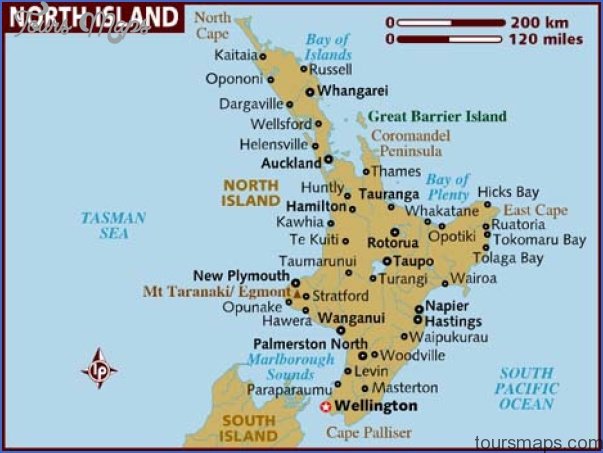

New Zealand North Island Map Photo Gallery

Some of the variability in growing conditions can, of course, be ameliorated. Irrigation is the main means of overcoming deficits in soil moisture but it remains a controversial viticultural practice. France allows irrigation under the AOC laws but only for vines under three years of age. Its argument is that after vines become

Central Otago vineyards use water sprinklers (above left), pot burners (above right), and wind machines (opposite) to fight frost. Felton Road (above left); Alan Kwok Lun Cheung (above right and opposite) established their roots must be encouraged to explore more deeply to tap additional reserves of nutrients and moisture especially in dry periods. But there is a simpler explanation. Few, if any, of their appellation wine regions need to irrigate because they seldom experience strong moisture deficits during the growing season. In France the legislation is also embedded in the conflict between the Midi and the prestigious appellations. After phylloxera, much of the Midi profited from being the first region back into production. In the last two decades of the nineteenth century it produced at high yields and grapes grown there were bought by producers from prestigious regions such as Bordeaux and Burgundy and passed off as their own.

Temperature is much more difficult to influence through vineyard practices than lack of moisture. Choosing a northerly aspect on sloping land and aligning the rows north and south on flatter land ensures that each side of the row is exposed to solar radiation and evens out the temperature in the canopy. Placing reflective material immediately under the vines increases the temperature in the row. Managing the canopy by plucking leaves in the fruit zone at veraison to expose the bunches to direct sunlight also hastens ripening. All of these techniques are practised in parts of New Zealand but it must be remembered that generally cool conditions in late summer and autumn are an advantage for growing vines. The window of opportunity for picking grapes that are physiologically ripe is longer because grapes tend to ripen more slowly than in warmer climates.

Given the potential of spring frost to kill buds and reduce or even destroy the crop, it is not surprising that within most viticultural regions participants in the industry have established networks of weather stations to monitor temperature and warn growers when severe early-morning frosts are imminent. When a frost warning goes out, enterprises jump into action. Their response depends on the nature of the frost and the protection systems they favour. If the frost is caused by a temperature inversion (warmer air trapped above a layer of cold air) helicopters are quickly airborne. Provided the cool layer is not too deep, they are often able to force the warm air down and mix it with the cold, thus avoiding damage to the buds or leaves of the vines. The terrestrial wind machines nestled in the frost-prone hollows of many viticultural regions work in a similar way. They set up a turbulence that disturbs the cool air ponding there. Viticulturists grumpy from disturbed sleep are common in the late spring.

Some vineyards, like Delegat’s 300 hectares on the left bank of the Ngaruroro River in Hawke’s Bay, have installed overhead sprinklers in addition to their drip irrigation. When frosts seem likely, the pumps are switched on by 4 a.m. to ensure that their two small reservoirs remain full while the vineyard sprinklers are spinning. By coating the vulnerable buds, shoots and young leaves in fine layers of ice, they are protected from frosts of several degrees below zero. The large enterprise ARA, on the west bank of the Waihopai in Marlborough, achieves a similar result more economically with overhead sprinklers that are used for both irrigation and frost protection.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit