The honeyguide was a bit less agitated; it had changed its call – softer in tone and much less persistent – and the bird stayed put on low branches next to this formidable tree. No longer was it flashing its white tail feathers; it had reached its destination … and seemingly ours. Lentaaya’s responses became muted, and from high in the tree canopy above us we could hear the loud hum of wild bees like a not-too-distant moped at full throttle. Unlike a moped, this hum sounded distinctly vicious.

But the huge tree with its smooth vertical trunk was impossible to climb without ropes and other equipment. Lentaaya was clearly disappointed. My response was more mixed; I was desperate to experience a bee nest being opened and the honeyguide being given some honeycomb as its ‘reward’ but I have to admit to some fear of a horde of aggressive wild bees descending in my direction.

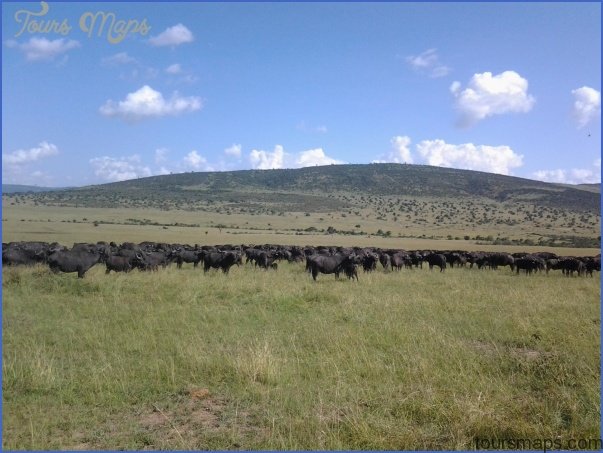

Kenya Wildlife Travel Packages Photo Gallery

Our honeyguide, though, was much more single-minded. It was very obviously irritated at our ineptitude. Big style! As we walked away reluctantly, Lentaaya talking to it all the while, it flew from branch to branch just above our heads, calling wildly and incessantly, flicking its wings and tail again, trying its level best to entice us back to the bees. We had the audacity to leave this clever bird in the lurch; we were walking away and nothing Lentaaya said to it – and he talked to it all the time – was going to soften the blow. The honeyguide followed us, keeping up its noisy appeal until we had walked more than 50 m away. And we could still hear it chattering in the distance as we headed slowly back to camp. I felt we had let it down.

The honeyguide/human relationship has probably been in existence for thousands of years, though its origins are a mystery. And there is an awful lot that isn’t well known about this unusual family of birds. There are 17 different species, all but two of them found in Africa south of the Sahara. The other two occur in Southern Asia south of the Himalayas. Some of the African honeyguides that live only in forests are so rarely seen, even though they might not be uncommon, that very little is known about them. And two of the species were only discovered during the last 50 years. The best known is the Greater Honeyguide, the one we had been following; a brown, black and dirty cream colour, similar to a very large sparrow, and with the male possessing a slightly chubby pink beak. Most experts believe that this is the only honeyguide known to guide people to a bee’s nest. Lentaaya’s day-to-day experience, though, is very different. He told me that while every Samburu knows about the lodokotuk (Greater Honeyguide) and its guiding behaviour, only Dorobo people can use other honeyguides, the silasili (Scaly-throated Honeyguide) and the airiguti (Lesser Honeyguide) as they are known to the Samburu.

‘When we meet a giochoroi [the general Samburu name for all honeyguides] the Dorobo start singing a particular song to invite the bird to show them the way to the nearest bee nest. We have a different song for each species. The song for the lodokotuk is a joke that asks the bird to lead us to the bees and requests it not to show the way to other Dorobos. The song for the silasili and the airiguti refers to them as a girl because their voices are softer than that of the lodokotuk,’ he said. It is this differentiation between the responses used by the Dorobo – depending on which species of honeyguide turns up – that I can’t find any mention of in the scientific literature. ‘But,’ Lentaaya added, ‘the lodokotuk is the best guide. The other two we use but they are not as accurate because they don’t take us close to the bee’s nest entrance and because they are less reliable at guiding. I collect about ten litres of honey in a year and sell it for about 2000 Kenyan shillings [£15] so I can pay for school fees for my children.’

What has long been established is that honeyguides are always attracted by human sounds, whether it is talking, chopping wood, cooking or something else. At a campsite they will often come very close, inspecting the tents and other equipment. They are certainly extremely curious birds.

But why, you might reasonably ask, does a honeyguide need people to break into the bee’s nest in the first place? It is because they don’t have large, strong beaks capable of doing the job themselves and because, in spite of having thickened skin, presumably to give them some protection, they are still vulnerable to being stung. Often, too, the bee’s nest is in an awkward spot; a cleft in some rocks for instance which is hard enough for a person to get access to and to which a honeyguide stands no chance of breaking in alone. Honeyguides have been seen in the cool early morning scraping bits of honeycomb at a nest they can partly access, presumably only then when the bees are still rather cool and dopey. But they have sometimes been found dead, too, and always close to a bee’s nest, killed by an overwhelming bout of bee stings. Meddling with wild bees can be a dangerous business.

So why eat bee honeycomb in the first place? For some unknown reason, honeyguides are particularly keen on a meal of wax and they are some of the few birds in the world that can digest it. They do eat other things, mainly spiders and a wide range of insects, including scale insects which have a waxy covering, as well as some fruits like figs. And when they gorge on honeycomb they are, of course, also eating quite a lot of bee eggs and grubs at the same time.

Dr Hussein Isack, an ornithologist at the National Museum of Kenya, Nairobi, is a honeyguide expert. He told me about his three-year research in northern Kenya in the mid-1980s where he found that 96% of wild honeybee nests were accessible to the birds only after people had opened them up first. So these birds have a lot to gain from their human relationship. He also found that tribesmen took an average of nearly nine hours to find a bee’s nest without any help from the birds but just over three hours when guided. And that was a conservative estimate of the time difference because it didn’t include days on which no nest was found, something that was rare indeed when the birds were doing the guiding.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

- Anniston Map

- Wildlife Travel Guide

- Wildlife Travel To Alonissos

- National Wildlife Travel