New Mexico Later Colonial Period (1680-1810)

Recent work by historians has suggested that the longtime image of colonial New Mexico as a cultural and economic backwater is an unfair stereotype. Nevertheless, it is clear that throughout most of the seventeenth century the colonial enterprise in New Mexico was tenuous and fraught with difficulty and uncertainty. Santa Fe was, in effect, an outpost of Spanish civil rule dominated largely by the power of the Franciscans, who seem to have had better success at regulating the Spanish than in evangelizing the Native Americans. The case of Cristobal de Anaya is instructive. Anaya was born in New Mexico and was a settler in the Bernalillo area, near present-day Albuquerque, which in the seventeenth century was a loosely affiliated group of Spanish ranchers amidst a predominantly Native American cultural and geographic setting. The Franciscans, the only Church presence in Santa Fe, had been delegated by the Mexican Inquisition to regulate doctrinal purity, being given powers to investigate and punish witchcraft, heresy, blasphemy, and sacrilege. The civil authorities had quarreled with the Franciscans over the extent of the latter’s authority in New Mexico, and Anaya, an outspoken character, sided with the civil authorities in this factional dispute. In 1661 he was arrested by agents of the Inquisition and sent to Mexico City in chains, where he spent 4 years in prison. He was also punished with a public penance before returning to Bernalillo.5 The tension between civil and religious authorities in seventeenth-century New Mexico was constant, as a sparsely populated Spanish colony fought for political preeminence.

One famous year in New Mexico history is 1680, which was decisive for the future of that Spanish colony. Pueblo Native Americans, who formed a kind of loose network or federation, rose up against the Spanish and succeeded in ousting

them from New Mexico. Their charismatic leader, Pope, urged the destruction not only of the Spanish colony but also of the imposed Catholic presence. The Pueblo revolt was a bloody orgy of revenge in which the Native American rebels burned down Spanish homes and government buildings, killed Spanish settlers, and drove the Spanish authorities from Santa Fe. Forced to flee, the Spanish colonists went south and installed a type of government in exile in today’s El Paso, Texas.

Pope and his closest leaders urged the Native Americans to reject the imposition of Catholicism and return to their pre-Hispanic religious traditions, many of which had been suppressed by the Franciscan missionaries. Psychologically, the impact of Pope’s orders must have been tremendous on the Spanish colonists and missionaries. Other areas of Mexico had offered resistance to missionary efforts and colonial rule, but there had not been a revolt as big and successful as the Pueblo revolt in the rest of New Mexico. Many felt that the New Mexico enterprise was a losing proposition; others despaired that the Church had suffered an unbearable setback; and civil officials worried that the strategic importance of Santa Fe would be irreparably lost.

But the Spanish would succeed in retaking Santa Fe. In 1688 Diego de Vargas, born in Madrid to a noble family, ascended the colonial ladder of military positions in New Spain, being nominated governor and captain general of New Mexico. In 1691 he formally took office. Over the next years he formed a coalition of Spanish soldiers and Native Americans loyal to the Crown, and he also managed to secure substantial royal funding for an expedition of reconquest. In December 1693 Vargas led his men into Santa Fe, first attempting diplomacy, but when this failed, he took it by force. On December 30 a bloody battle in which more than 80 Native Americans perished resulted in the victory of the Spanish, who reestablished their official rule over Santa Fe. In a symbolic gesture, a Franciscan friar celebrated a mass the next day to give thanks for the reestablishment of Catholicism, and Vargas promised celebrations at the feet of La Virgen Conquistadora, a statue which had been brought to New Mexico by Alonso de Benavides in 1626. Because the Virgen was the patroness of New Mexico and a symbol of the Spanish Catholic conquest, the mass and obsequies at the statue’s feet could not have been more dramatic.6

For the next century New Mexico developed into a mature colony, though it remained defined by its position on the geographic, economic, and cultural periphery of New Spain. Though the seventeenth century was characterized by itinerant colonial rule and sparse population on the part of the Spanish, the eighteenth century saw clear changes. The raids by nomadic Native Americans on Spanish settlements eventually forced a reconsideration of settlement patterns. If previously the Spanish had preferred to live in sparsely populated and distant ranchos largely along the Rio Grande, they now began to settle more densely in towns. The Spanish (or Hispano) population grew at a much greater rate than the

Pueblo population, which placed strains on the availability of land and which led to a yet more densely populated Spanish core, though it was still far less dense than central Mexico. Finally, a series of royal legislative changes, known as the Bourbon Reforms, made for dramatic changes in economic systems in the New Mexico colony.

The reconquest of New Mexico set in motion greater Spanish settlement and the establishment of new colonies, towns, and municipalities. Villa was a legal term for a municipality that, according to ancient Spanish law and custom, applied to a town that had certain specific privileges and rights, as opposed to a pueblo (which was usually Native American) or scattered settlements. Santa Fe had already been long established as a villa, but the eighteenth century saw the transformation of New Mexico; though it had not become an urban center, at least it had changed into a colony with a much greater density of Spanish settlers and citizens (vecinos). Albuquerque, much further to the south in the Middle Valley of the Rio Grande, was established in 1706. Through the rest of the eighteenth century Albuquerque would take a backseat to Santa Fe, where the oldest Spanish families resided and where the governor’s palace was situated, making it the administrative and political center of the colony, whereas Albuquerque was principally an agricultural town.

Land acquisition patterns were influenced heavily by the process of land grants. The Spanish Crown granted land in blocks to both Spaniards and Native Americans. Part of the logic behind giving specific parcels of land to Native American groups stems from the lengthy Spanish colonial policy of accommodating Native Americans into the broader civil polity of the royal system, provided that those Native Americans agreed to pay their tribute requirements and not to raid Spanish settlements. In the case of New Mexico, which was sparsely populated, this meant an uneasy balance between four principal ethnic-social groups The Spaniards, though the nominal rulers of the colony, were always considerably outnumbered by Native Americans. Still, Spanish populations rose in comparison with Pueblo and other Native American populations throughout the eighteenth century.

Pueblo Native Americans were seen by missionaries and Spanish officials as higher-order Native Americans, given their tradition of town settlement and fixed agriculture. The Jesuit Jose de Acosta, among others, had viewed Native American societies and groups along a continuum of civilization, and the Pueblos were always seen as superior to other Native American groups but inferior to Spaniards. The various nomadic Plains Native Americans the Comanches, for example were viewed as not only ethnically but civilizationally distinct and inferior to the Pueblos. Their lack of settled towns and steady agriculture and their tendency to rely on raiding as a form of economy made Spaniards see them as not only dangerous (because they often raided both Pueblo and Spanish settlements) but also essentially barbaric. Finally, the genizaros were Hispanicized Native

Americans who had been captured and sold into servitude to Spaniards. Their exposure to Spanish custom and language made them partially Hispanicized, but they were never viewed as properly Spanish, given their ethnic background.

The geographic isolation made bartering the fundamental method of exchange. The lack of coinage and the omnipresence of ranching and farming as ways of life meant that the exchange of manufactured goods such as textiles and clothing for animal products or vegetables was fundamental. According to some historians, this led to a more familial and personal system of doing business. Stripped of the impersonal nature of formal economies, New Mexico emerged culturally as a place where one’s place in society and one’s word became extremely important.

Though ethnic mixing took place in New Mexico as it did in other parts of New Spain, New Mexico’s isolation caused the emergence of a very strong sense of Hispano or Spanish identity among Hispanic settlers. Even though Spanish settlements were surrounded by Native American settlements, they remained fundamentally set apart from Native American societies. Spaniards, many of them Mexican-born criollos, retained a strong cultural identification with their Spanishness. The irony of this situation is that as members of a frontier society, these Spaniards would never have been accepted back in the urban worlds of Mexico City, Seville, or Madrid, as they would have rather been seen as backward. Yet, it was precisely during this time that Nuevomexicanos developed a sense of unique cultural identity. The shrine at Chimayo became an important religious site in the development of identity. Indigenous materials were used by religious artisans to craft a specifically New Mexican style of art. And the availability of certain materials led to the development of specific architectural styles for example, adobe houses and churches and culinary traditions. Moreover, Nuevomexicanos continued to speak a type of Spanish that preserved very old Castilian forms, which had gone out of use in other parts of New Spain.

In the mid-nineteenth century the Spanish Crown began a series of political and economic reforms that attempted to reorganize its empire and colonial holdings. Among its goals was stricter control of tax collection as well as some freeing up of the previously closed trade systems that forbade non-Spaniards from engaging in direct trade without special dispensations in the Spanish Americas. Despite these rules and various royal prohibitions on foreign trade, New Mexico’s distance from the centers of colonial power meant that trade fairs in Taos and Pecos flourished. The Bourbon Reforms, as these new rules were called, also set the ideological stage for independence movements in Latin America because they imposed governors, known as intendants, who were from Spain and not the Americas. The local criollo elites, who had come to dominate local politics, chafed at these impositions. When Napoleon invaded Spain in the early 1800s, criollos saw an opportunity to rebel against monarchic rule. Beginning in 1810 and led largely by insurgent priests such as Miguel Hidalgo, New Spain successfully

rebelled against Spain, which in 1821 led to the establishment of an independent nation: Mexico.

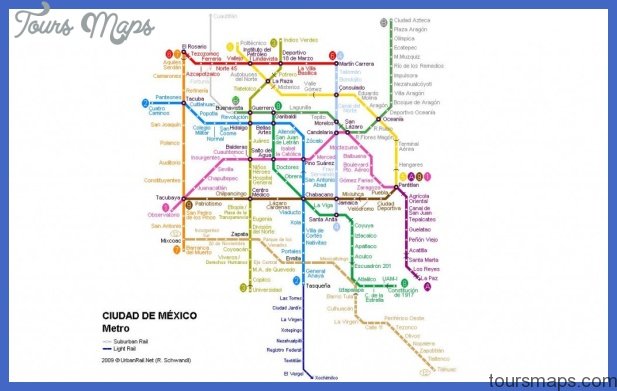

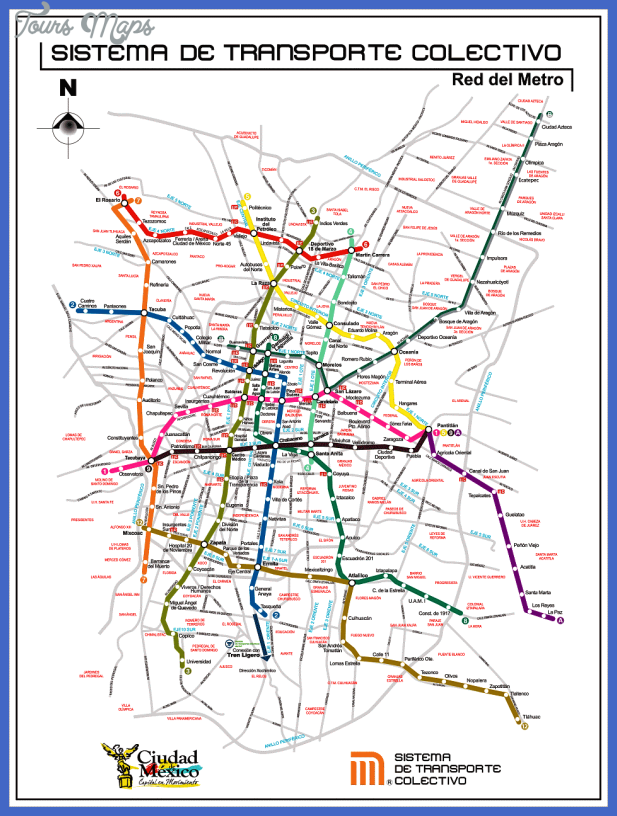

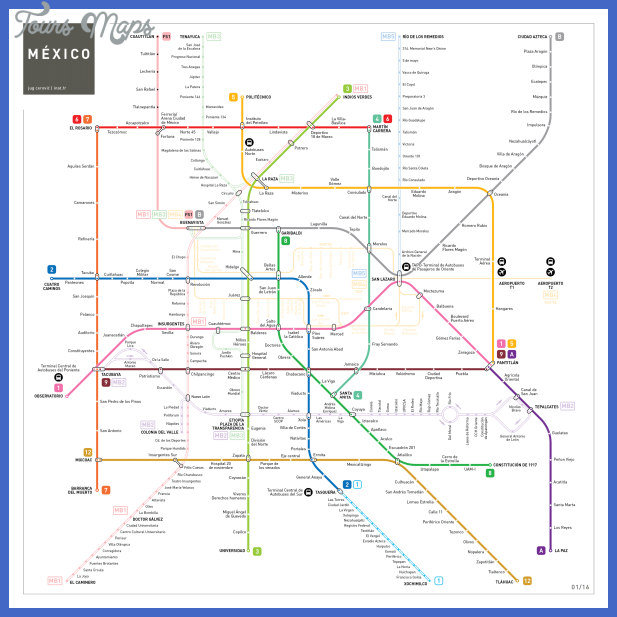

New Mexico Subway Map Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map

- Explore Gumdag, Turkmenistan with this detailed map

- Explore Telfes im Stubai, Austria with this detailed map

- Explore Langenselbold, Germany with this detailed map

- Explore Krotoszyn, Poland with this detailed map