Managing a variable climate

Although the average conditions described in these maps are a useful indication of where different varieties of grapes might be grown, they are not sufficient to understand the complexity of the way that grape growers must interact with their natural environment if they are to be successful. The weather of the growing season is different each year. In addition, the growing conditions of one year are carried forward to the vine’s behaviour in the next year through the accumulation of proteins and other elements in the trunk, branches and roots of the vine, and in the fertility of next year’s buds. These circumstances make it necessary to manage the vine’s growth each year to attempt to achieve the optimal size of crop for the quality of wine being produced.

This management is a difficult task because it must be done without knowing what the weather is going to be in any single year. Pruning to a number of buds, known from accumulated empirical experience to produce the desired crop, is the main way most viticulturists manage crop levels. But weather conditions before and during flowering and setting of the berries, or hail afterwards, can have huge effects on the size of the crop, as can the temperature during the growing season in ripening it. So too does rain when bunches are almost ripe. The plant quickly absorbs moisture and pumps it into the berries. They swell and may split which makes them prone to mildews and botrytis. In general, therefore, many viticulturists producing quality wines prune to set a larger than necessary number of bunches and vendange en vert (literally, ‘harvest in the green’) by cutting off bunches towards veraison (the onset of ripening) if the vines seem unlikely to be able to ripen their crop.

New Zealand Earthquake Map Photo Gallery

The degree-day is one way to assess such variability. The measure was originally developed, based on average monthly temperature statistics, to express the suitability of different climates to grow various crops. It became popular in the United States as a measure for distinguishing different thermal environments for the vine, especially in California, where in the mid-twentieth century viticulture was expanding into new areas. It proved useful there because variations in temperature from one region to another, or even within the same region, such as northern California, are considerable. Aspiring grape growers were able to judge which varieties of grapes they might grow in their region or sub-region because the degree-day distinguished the full range of growing conditions from the cool (coastal California north of San Francisco) to the moderately hot (Napa Valley) to the extremely hot (Central Valley).

Calculation of degree-days assumes that the vine starts actively growing when temperatures are above 10°C. For each month of the growing season (October to April in the southern hemisphere and April to October in the northern) temperatures above 10°C are summed. The normal calculation begins with the average temperature of the month, subtracts 10 from it, and multiplies the remainder by the number of days in the month. The degree-day is therefore superficially attractive as a measure because it is simple to calculate and gives the impression of energy accumulating over the growing season.

The measure has several deficiencies, however, the main one being that minimum temperatures during the night, when the vine is not photosynthesising, can unduly influence the result. Such underestimation was one of the main reasons some scientists were overly sceptical about the prospects for viticulture in Central Otago. Many scientists, but initially James Prescott, have also pointed out that degree-days correlate closely with even simpler measures such as the average temperature of the warmest month discussed earlier. This similarity results because the high point of the regular annual temperature curve predicts other points on the curve very accurately. Despite these limitations, and largely because of its simplicity and familiarity, many enterprises continue to use the degree-day to summarise thermal conditions in New Zealand and elsewhere. It is their common currency for discussing temperatures in different years.

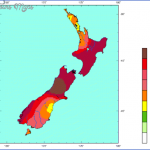

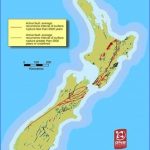

The degree-day is, therefore, a useful measure to illustrate the variability in atmospheric conditions that viticulturists face from year to year in all regions of New Zealand. Two maps, one of average degree-days calculated over a 30-year period (1975 to 2005) and a second of degree-days in the 1997/98 growing season, show the magnitude of the differences (Figures 4.9, 4.10). The 1998 vintage is used as an example because in most New Zealand regions it is the warmest season on record since grapes became an important crop. Grape growers and wine enterprises struggled with decisions about when they should pick. In Marlborough, where Sauvignon Blanc was by then clearly the most important variety, the decision was especially difficult. Winegrowers wanted to retain the acidity, vibrancy and vitality that characterise the aromas and flavours of Sauvignon from this region, but were also wary of picking too early.

In this 1997/98 growing season the differences in degree-days from the average were substantial. All grape-growing regions except Central Otago had passed their average expectations by more than 200 degree-days. In Marlborough’s case this meant up to 25 per cent more solar energy than normal. In a ‘normal’ year it would expect a total approaching 1200 degree-days, whereas by vintage 1998 some sites in the Wairau and Awatere valleys received between 1400 and 1500 degree-days. (Even Cabernet Sauvignon might have ripened effortlessly in Marlborough and Martinborough in that season.) Marlborough winegrowers were unsure whether to pick or leave their grapes on the vine. Some delayed and regretted the decision because the grapes did become overripe and began deteriorating. A few growers picked part of their crop quite early and the rest later – probably the best solution considering the uncertainty in achieving the balance in sugar levels, acidity and flavours they were seeking. ‘We’d do it a damn sight better if we had a similar season next year!’ commented Peter Babich laconically three months after the 1998 vintage. Empirical experience counts.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit