It has been almost five months in the low-lying atolls with only sporadic Internet and infrequent phone use. Our bodies are lithe and strong.

There have been no hot showers, no fancy supermarkets or gourmet chocolates, no magical faucet spouting an endless flow of water. Provisions and comforts are modest, but my spirits are surprisingly high.

Amazingly, we’ve used less than a gallon of gasoline for Swell’s daily energy requirements, including refrigeration, lights, computer, music, and the water pump. The atolls have no mountains to block the sun or trades, so the solar panel and wind generator constantly replenish the batteries. We catch rainwater and wash our clothes by hand.

It’s simple living and hard work, but this modest lifestyle awakens gratitude for even the smallest pleasures. If we exist in complete ease, with unending options, I think it’s harder to truly enjoy luxuries and extravagance. “It’s important to distinguish needs from wants,” Barry used to say. Contrast helps develop gratitude. Even though Western society idealizes luxury, to me too much comfort is caustic.

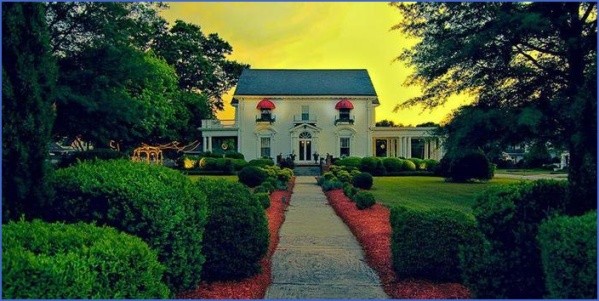

Simply Divine Photo Gallery

Out here, simple things evoke such abundant gratitude finding a safe anchorage after being at sea, savoring a just-caught fish, the rare real shower, sleeping in clean sheets, the unexpected kindness of a stranger, or finding a little wave to glide on! Moonbeams on the sea at night make me feel richer than any diamond ever could.

But by contrast, things with Rainui are far from simple. Some days he presses me to my limits, torturing me with words, and acting so unfair that I lash out. I can tell he likes it when I get upset, as if it assures him of my love. Sometimes when his foul mood crowds the cabin, I go ashore.

I try to meditate, or sometimes I cry a little, but usually I just end up sitting silently on a beach beside the lagoon or reef, watching the creatures around me: hermit crabs, bees, ants, circling terns, fish along the shoreline, flies, mosquitos, crabs, spiders, trees, vines, long-legged sandpipers. I realize that they all have messages for me patience, hard work, perseverance, slowing down, relaxation, letting go, being still, or getting a higher perspective. They remind me that mine is one among the millions of life dramas going on all over Earth. Near them, I feel less alone. I hear a voiceless voice telling me that today is an exquisite phenomenon.

Urchin spines wave in the flow of the water over the reef. I watch flying fish wiggle free of the sea surface and hover a hundred yards with their wings glowing golden in the evening light. A baby humpback whale breaches nearby. Frigates circle and scissor in the tempestuous trades. Sharks patrol the shallows at sunset. Palm fronds dance on and on in the wind.

I don’t know what it is about the direct contact with wilderness that nourishes me. Maybe it’s what others feel in church or making art. I feel so drawn to its purity and unfathomable intelligence, its seemingly individual parts all working together as one. Its rhythms and extremes. Shadows and light. Serenity and chaos. Beginnings and endings. I recognize the same things going on inside my own little universe, and I know that I am That. Namaste!

Barry, too, knew the deeper value of wild places and the lessons they offer, returning to wilderness as often as he could. Like him, I cherish seeing the waters, the plants, the animals in a wild and free state just how I love to be the most. They are perfect that way. Perfectly divine. Recognizing that we are all interdependent somehow makes me part of this grand and unexplainable miracle. All of us spark from the same Infinite Spirit, Source, God, Jah, Allah, Mana that connects everything.

If we can see everything as sacred, we may have a chance at healing the planet. Personal healing contributes too. And like Barry mentioned in his final letter, eco technologies could provide healthier ways to respect the planet while upholding modern lifestyles electric cars mean cleaner air; grassroots movements like “permaculture” and urban gardens mean food production without the use of agro chemicals; wind and solar farms and bioplastics mean greener homes and cleaner living. Expanding compassion to include all life might mean less suffering, and might allow humans to live more meaningful lives.

Looking out at all the sacredness surrounding me, I fear that if we never have these sorts of close encounters with open spaces and wild creatures, if our only contact with wilderness and animals is through a television and our pets, we risk not caring whether they exist at all. We risk not feeling our spirits stirred. We risk losing a vital part of ourselves and a vital avenue to knowing this extraordinary feeling of connection.

“God” is no longer a distant mystery to me anymore. I feel the Divine within me and every time I look out my window.

Bait for Breakfast

As cyclone season approaches, we ready Swell to sail north to the safer latitudes in The Land of People. After a trying eight-day passage to the mountainous archipelago where Mom and I first arrived, Rainui and I straggle into an uninhabited bay to dry out, rest, and reorganize. It still amazes me how the thrill of landfall can so easily erase the misery of a difficult passage.

The tall surrounding cliffs, sprawling valley, and echoing bleats of mountaineering juvenile goats overwhelm our senses. While ashore to stretch our legs and explore, we find loads of wild food, and the locals in the nearest village assure us that we are welcome to help ourselves. After months on islands that can’t support such tropical lushness, the wild oranges, papayas, mangos, limes, pumpkin, red bananas, grapefruit, guavas, and even taro and sweet potato are the sweetest treasures. We sit in the shade of a loaded mango tree up the valley, stuffing ourselves on golden flesh until it hurts, and then float down the cool river back to the beach.

But apart from the edible bliss and tranquility of the valley, there is an unmistakable aura of tragedy in the air. Remnants of the ancient civilization that once blossomed here are all around us. Stacked stone foundations of homes line the river for the length of the valley. The ancient Polynesians who lived here were skilled masons. Like Hiva’s father had explained on my first pass through these islands, the Land of People supported an estimated 100,000 inhabitants before the catastrophic population collapse.

In the sixteenth century, the French took forceful claim to the islands in a spirit similar to European settlers’ horrific treatment of Native Americans. The islanders lacked natural immunity to introduced diseases. Despite pleas from foreigners living here at the time, France refused medical assistance to the native peoples, taking them for “savage cannibals.” But which is more barbaric, the occasional human barbecue or infecting an entire race of people and leaving them all to die? The population shrunk to under 2,000 by 1925. Today, many native descendants have moved out of isolated valleys like this one to be closer to schools, stores, imported supplies, and more opportunities for work.

We enjoy hopping around the islands, until one afternoon after chatting, an older local man scribbles down the name of a bay.

“You will like it here,” he says with a convincing smile, and hands me the paper. We arrive a week later to find a deep bay with two nice waves, a big open-air copra storage area that’s great for yoga, a shower spigot nearby with potable water, surrounding mountains to forage, and a quiet beachside community. Kids follow us on fruit-hunting missions and we take them out and push them into waves when the conditions are right. We pluck bunches of watercress from streams, surf and bodysurf, fish in the nearby waters, jump off the cliffs, and make friends with local families. They teach us to cook traditional delicacies and weave palm-frond hats. Rainui pursues wild pig and goat with hunter friends, while I enjoy peaceful mornings in the galley after a surf making fresh juices and jams, fermenting vegetables, sprouting seeds, or baking.

After more than a month anchored here, we start to uncover more details about life in the bays, hills, trees, and rocks. It occurs to me that regional plant and animal knowledge was commonplace in native cultures worldwide, and now most of us don’t even know that we don’t know our local plants. I ponder the effects of this widespread alienation from our nearby environments. Could it be contributing to the increased rates of anxiety and depression? Chronic disease and staggering drug use?

Rainui and I don’t go to the store with a list; we go to the hills with gratitude for whatever the earth has to offer. The beauty and the surprises found in the hills make me want to leap out of bed each morning. Rainui’s moods seem more stable too. Again, the process of collecting food feels rewarding in itself: the sticky sap on my fingers, learning how to tell when fruits are ready to be picked, feeling that burst of adrenaline as I stretch out on a branch hoping to reach just one more mango. I see my food alive and thriving, versus buying it in a market. All of this reminds me of the complex processes and daily miracles that happen before the food goes in my mouth. That appreciation transfers into our meals, and food continues to take on rich new dimensions.

On an afternoon exploration, we meet Mami Faatiarau, a courageous seventy-nine-year-old woman living with her disabled grandson in an empty valley at a nearby bay. She’s fit and spry still hunting wild pigs, raising goats, collecting shellfish, harvesting her own fruits, cooking in the traditional underground oven, and walking four miles each way to the closest village. Maybe doctors should prescribe fresh air, nature, and gardens to treat more of our modern ailments?

As we stay on in the bay, algae grows thick on the anchor lines, and soon Swell has developed a little ocean ecosystem under her hull. Shrimp, crab, algae, tiny young fish, a seahorse, turning bait balls, passing tuna schools, and a roaming manta ray family make us feel part of the underwater party. We often wake to the sound of thrashing near the hull as tuna or other apex predators chase the baitfish into such a frenzy that some of them launch from the sea onto Swell’s deck. I run up and chase after their wiggling bodies, thanking each one for its life with a kiss of gratitude, then tossing them into the pan for a low-on-the-food-chain breakfast delicacy.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit