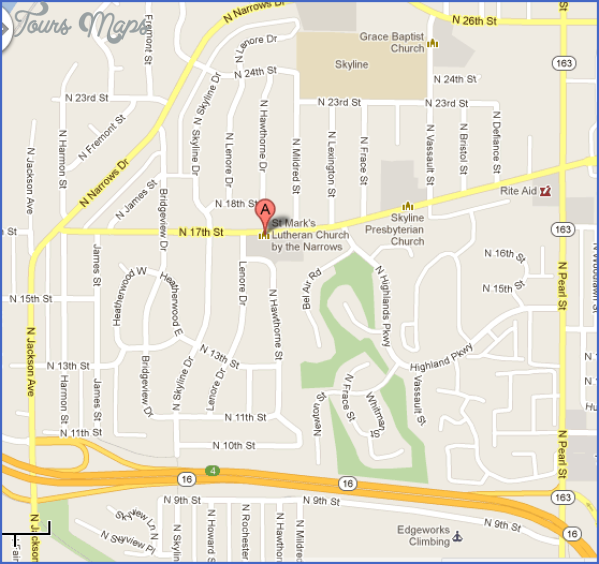

TACOMA NARROWS BRIDGE MAP

The bridge’s explosive collapse was deemed “the Pearl Harbor of engineering.”

On the morning of November 7, 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapsed in 42-mile-an-hour winds that swept across Puget Sound, thirty miles south of Seattle. The third-longest suspension span in the world at more than a mile long, it had been open only four months. Even though the bridge’s violent demise was documented in dramatic photographs and film footage, technical experts still disagree on the exact nature of the phenomenon that led to its notorious collapse.

When it opened, the bridge’s deck undulated so muchharmlessly, it was thoughtthat thrill seekers sought it out to experience the roller-coaster-like ride across. Others went miles out of their way to avoid “Galloping Gertie,” as the bridge was nicknamed even before it opened. Veteran designer Leon Moisseiff (1872-1943) had consulted on nearly every large suspension bridge built in America before 1940. He configured the Tacoma Narrows’ long center span with an exceptionally narrow roadway, only 39 feet (12 meters) wide, because the swift current and poor riverbed at that location prevented intermediate foundations. Supported by shallow plate girders instead of traditional deep, stiffening trusses, the proposed bridge was economical and elegant. By the 1930s, as cars replaced heavier railcar loads, the use of strengthening trusses was becoming obsolete. Later it was realized that the sheer weight of these trusses canceled out the deleterious effect of aerodynamic forces on the structure. It was not realized that the aerodynamic forces which had proven disastrous in the past to much lighter and shorter flexible suspension bridges would affect a structure of such magnitude as the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

TACOMA NARROWS BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

Moisseiff’s sterling reputation, coupled with his designs for similarly slender suspension bridges, blinded engineers, who considered aerodynamic failure a remote possibility. The lone dissenter to the proposed designT. L. Condron, a septuagenarian engineer who recommended widening the deckwent unheeded.

Gertie came to an abrupt end. Simply put, the deck’s plate girders resisted the wind, unlike an open truss, which would have allowed the wind to pass through the structure. The shallow deck, combined with its slim proportions, made the structure especially vulnerable. The bridge’s oscillation amplified until its convolutions tore several suspenders loose, and the span broke up. Miraculously, the only fatality was a dog, Tubby, that did not manage to escape his master’s car before it fell into the Narrows.

Immediately following the collapse, the Washington Toll Bridge Authority and the Federal Works Agency established investigative commissions. The federal commissioners, who included the esteemed engineers Othmar Ammann and

Theodore von Karman, exonerated Moisseiff, observing that while the bridge’s shortcomings were obvious in hindsight, its design had met all criteria for acceptable practice. The report’s tone suggests that the engineering industry as a whole, in its relentless pursuit of streamlined bridges of unprecedented length, was guilty of ignoring aerodynamic forces in their calculations.

All agreed that the bridge could not be repaired. Discussions about how to dispose of what remained of it were halted by the United States’ entrance into World War II in 1941. With steel redirected to the war effort, reconstruction was also put on hold; the Narrows would not be crossed for another decade, and for the next quarter century no suspension bridge would be built without a stiffening truss.

Frederick “Burt” Farquharson, an engineering professor at the University of Washington who had been studying the bridge’s movement, was there to capture the bridge’s death rattle in these dramatic photographs. For ten days almost to the minute, the bridge at Remagen was kept open, having miraculously survived attempts on both sides to blow it up. Despite round-the-clock repairs, the German demolition charges and constant Allied shelling finally took their toll. On March 17, 1945, the bridge collapsed and slowly sank into the Rhine. Twenty-eight Allied soldiers who were repairing the bridge at the time it collapsed died.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore East Lindfield, Australia with this detailed map

- Explore Bonferraro, Italy with this detailed map

- Explore Doncaster, United Kingdom with this detailed map

- Explore Arroyito, Argentina with this Detailed Map

- Explore Belin, Romania with this detailed map