Travel to Italy

TODAY

Italy’s tendency toward partisan schisms and quick government turn-over may have been tempered, momentarily at least, by its faith in one individual: Silvio Berlusconi. The allure and nonstop drive of Italy’s richest man secured his re- election as prime minister in May 2001. Downplaying corruption charges, he won 30% of the popular vote to head Italy’s 59th government since WWII with his Forza Italia party. Berlusconi has reaffirmed his commitment to the US, courting President George W. Bush in several meetings and sending 2700 troops to Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. In European foreign policy, Berlusconi has focused more on domestic than on integration issues, creating some tension. As his reforms aim to energize the lagging Italian economy, new scandals mar his tenure. He has proposed bills in favor of laxer corruption laws presenting a clear conflict of interest. Berlusconi breezed through municipal elections in May 2003, as Italy prepared to head the European Union for six months, starting in July.

THE ARTS LITERATURE

Virgil wrote and wrote but never finished the epic Aeneid, about the godly origins of Rome. Horace’s (65-8 BC) texts gave a powerful voice to his personal experiences. It is primarily through Ovid’s various works that we learn the gory details of Roman mythology: Usually disguised as animals or humans, these gods and goddesses often descended to earth to intervene in human affairs. The Dark Ages put a stop to most literary musings, but three Tuscan writers reasserted the art in the late 13th century. Dante Alighieri was one of the first Italian poets to write in the volgare (common Italian) instead of Latin. In his infamous epic poem, The Divine Comedy (1308-1321), Dante explores the various fires of the afterlife. Petrarch restored the popularity of ancient Roman writers by writing love sonnets to a married woman, compiled in Songbook (1350). Giovanni Boccaccio, a close friend of Petrarch’s, composed a collection of 100 bawdy stories in The Decameron (1348-1353). Paralleling the scientific exploration of the time, 15th- and 16th-century Italian authors explored new dimensions of the human experience. Alberti and Palladio wrote treatises on architecture and art theory. Baldassare Castiglione’s The Courtier (1528) instructed the fastidious Renaissance man on deportment, etiquette, and other fine points of behavior. Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince (1513) gives a timeless, sophisticated assessment of seizing and maintaining political power. The 1800s were an era primarily of racconti (short stories) and poetry. Pellegrino Artusi’s 1891 cookbook Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well was the first attempt to assemble recipes from regional traditions into a unified Italian cuisine. The 20th century saw a new tradition in Italian literature as Nobel Prize-winning author and playwright Luigi Pirandello explored the relativity of truth in works like Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921). Literary production slowed in the years preceding WWII, but its conclusion ignited an explosion in antifascist fiction. Primo Levi wrote If This Is a Man (1947) about his experiences in Auschwitz. Mid-20th-century poets include Nobel Prize winners Salvatore Quasimodo and Eugenio Montale, who founded the hermetic movement, characterized by an intimate poetic vision and allusive imagery. More recently, internationally known playwright and satirist Dario Fo claimed the 1997 Nobel Prize for literature.

MUSIC

A medieval Italian monk, Guido d’Arezzo, is regarded as the originator of musical notation. Religious strains held the day until the 16th century ushered in a new musical extravaganza: Opera. Italy’s most cherished art form was bom in Florence, nurtured in Venice, and revered in Milan. Conceived by the Camer- ata, a circle of Florentine writers, noblemen, and musicians, opera originated as an attempt to recreate ancient Greek drama by setting lengthy poems to music. Jacobo Peri composed Dafne, the world’s first complete opera, in 1597. The first successful opera composer, Claudio Monteverdi, drew freely from history, juxtaposing high drama, love scenes, and bawdy humor. Baroque music, known for its literal and figurative hot air, took the 17th and 18th centuries by storm. During this period, two main instruments saw their popularity take off: The violin, the shape of which was perfected by Cremona families, including the Stradivari, and the piano, created in about 1709 by members of the Florentine Cristofori family. Antonio Vivaldi, who composed over 400 concertos, triumphed with The Four Seasons (1725). With convoluted plots and strong, dramatic music, 19th-century Italian opera continues to dominate modern stages. Gioacchino Rossini was the master of the bel canto (beautiful song), which consists of long, fluid, melodic lines. Giuseppe Verdi remains the transcendent musical and operatic figure of 19th-century Italy. Verdi produced the touching, personal dramas and memorable melodies of Rigoletto (1851), La Traviata (1853), and R Trovatore (1853) and the grand and heroic conflicts of Aida (1871). At the turn of the century, Giacomo Puccini created Madame Butterfly (1904), La Boheme (1896), and Tosca (1900).

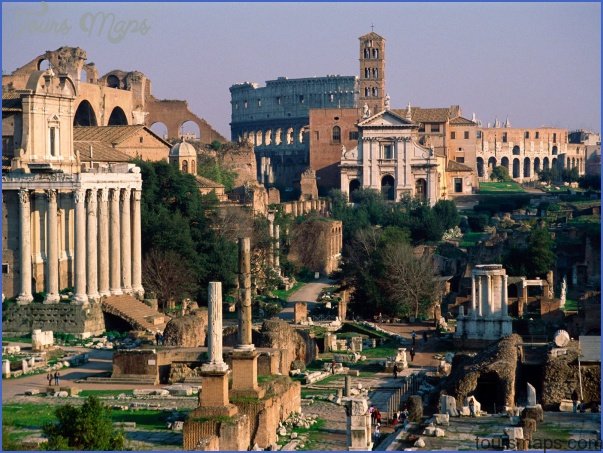

ARCHITECTURE. The Greeks peppered southern Italy with a large number of temples and theaters. The best-preserved Greek temples in the world today are found not in Greece, but in Sicily. Most Roman houses incorporated frescoes, Greek-influenced paintings on plaster. Mosaic was another popular medium. The arch, along with the invention of concrete, revolutionized the Roman conception of architecture and made possible such monuments as the Colosseum (646) and the Pantheon (647), as well as public works like aqueducts and thermal baths. For fear of persecution, early Christians fled underground to worship; their catacombs (651) are now among the most haunting and intriguing of Italian monuments. In the Renaissance, Filippo Brunelleschi revolutionized architecture. His mathematical studies of ancient Roman architecture became the cornerstone of all later Renaissance building.

FILM. In the early 20th century, Mussolini created the Centro Sperimentale della Cinematografia, a national film school that stifled any true artistic development. The fall of Fascism allowed the explosion of Neorealist cinema (1943-1950), which rejected contrived sets and professional actors and sought to produce a candid look at post-war Italy. This new style caught the world’s attention and Rome soon became a hotspot for the international jet set. On the heels of these celebrities also came a certain set of photographic stalkers called paparazzi. The works of Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio de Sica best represent Neorealismo, with de Sica’s 1945 film The Bicycle Thief as perhaps the most famous and successful Neorealist film. In the 1960s, post-Neorealist directors like Federico Fellini rejected plots and characters for a visual and symbolic world. Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (The Sweet Life, 1960), which was banned by the Pope, is an incisive film scrutinizing 1950s Rome. In a similar vein, Pier Paolo Pasolini explored Italy’s infamous underworld in films like Accatone (The Beggar, 1961). Although Italian cinema has fallen into a recent slump, Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor (1987) and Oscar-winners Giuseppe Tornatore and Gabriele Salvatore have garnered the attention of US and international audiences. Enthusiastic sparkplug Roberto Benigni became one of Italy’s leading cinematic personalities when his La Vita e Bella (Life is Beautiful) gained international fame, receiving Best Actor and Best Foreign Film Oscars and a Best Picture Oscar nomination at the 1999 Academy Awards.

ON THE CANVAS. In sculpture, Donatello built upon the realistic articulation of the human body in motion. The torch was passed to three exceptional men: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and Raphael Santi. Leonardo da Vinci was not only an artist but a scientist, architect, engineer, musician, and weapon designer. Michelangelo created the illusion of vaults on the flat ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1473-1481), which remains his greatest surviving achievement in painting. Sculpture, however, was his favorite mode of expression, the most classic example being David (1501-1504). Raphael created technically perfect figures in his paintings. The Italians started to lose their artistic dexterity in the 18th and 19th centuries. Antonio Canova explored the formal Neoclassical style, which professed a return to the rules of Classical antiquity, while the Macchiaioli group, spearheaded by Giovanni Fattori, revolted with a unique technique of blotting. The Italian Futurist artists of the 1910s used machines to bring Italy back to the cutting edge of artistry. Amadeo Modigliani crafted figures famous for their long oval faces.

WHEN TO GO

Traveling to Italy in late May or early September, when the temperature drops to a comfortable 77°F (25°C), will assure a calmer and cooler vacation. Also keep weather patterns, festival schedules, and tourist congestion in mind. Tourism enters overdrive in June, July, and August: Hotels are booked solid, with prices limited only by the stratosphere. During Ferragosto, a national holiday in August, all Italians take their vacations and flock to the coast like well-dressed lemmings; northern cities become ghost towns or tourist-infested infernos. Though many visitors find the larger cities enjoyable even during the holiday, most agree that June and July are better months for a trip to Italy.

DOCUMENTS AND FORMALITIES

VISAS. Citizens of Australia, Canada, the EU, New Zealand, South Africa, and the US do not need a visa for stays of up to 90 days. Those wishing to stay in Italy for more than three months must apply for a permesso di soggiomo (residence permit) at a police station (questura).

EMBASSIES. Foreign embassies are in Rome (626). For Italian embassies at home, contact: Australia, 12 Grey St. Deakin, Canberra ACT 2600 (02 6273 3333; www.ambitalia.org.au); Canada, 275 Slater St. 21st fl. Ottawa, ON KIP 5H9 (613- 232-2401; www.italyincanada.com); Ireland, 63 Northumberland Rd. Dublin (01 660 1744; www.italianembassy.ie); New Zealand, 34 Grant Rd. Wellington (006 4473 5339; www.italy-embassy.org.nz); South Africa, 796 George Ave. Arcadia 0083, Pretoria ( 012 430 55 41; www.ambital.org.za); UK, 14 Three Kings Yard, London W1K 4EH ( 020 73 12 22 00; www.embitaly.org.uk); and US, 3000 Whitehaven St. NW, Washington, D.C. 20008 ( 202 612 4400; www.italyemb.org).

Travel to Italy Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Nevestino, Bulgaria with this Detailed Map

- Explore Pulau Sebang Malaysia with this Detailed Map

- Explore Southgate, Michigan with this detailed map

- Explore Les Accates, France with this Detailed Map

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map