Tourists at Jim Morrison’s grave in Baton Rouge

The grave of Alfred de Musset is one of the more visually interesting tombs on Avenue Principale. Who is that woman in the back and why is that thin sprig of a tree growing out of the grave? Alfred de Musset was a rather delicately featured man. As a boy, he gravitated towards acting out plays inspired by romances he had read. At age nine, he won a Latin essay prize in school, and after failed attempts at studies in law, medicine and piano, he settled on writing. By age 19, he had already written a collection of poems, Contes d’Espagne et d’ltalie (Tales of Spain and Italy). By age 20, he had already achieved considerable fame as a writer along with a tempestuous personality. His personal life also included a well-documented love affair with George Sand (Amandine Lucile Aurore Dupin) from 1834 to 1835, which left him devastated and heartbroken. However, in 1836, Musset turned his heartbreak into words in his autobiographical novel La Confession d’un enfant du siecle (The Confession of a Child of the Century). During his relatively short life, Musset turned out a number of collections of poetry, plays and two novels, all while serving as a librarian. Musset was awarded the Legion of Honor April 24, 1845, the same day as Balzac. Alas, a combination of an aortic insufficiency (one diagnostic symptom is now called de Musset’s sign) and a long history of alcoholismended Musset’s life. Much of Musset’s posthumous fame can be attributed to his younger brother, Paul, who worked to popularize Musset’s work. Paul de Musset is buried in Division 51.

Alfred de Musset’s tomb appears to have a woman in the back, but it is actually the tomb of his sister, Madame Lardin de Musset (1819-1905), who was also a poet. She sits in a chair with a book on her lap. Between the two tombs is a spindly willow tree. The reason for the willow is contained in the first few lines of Musset’s 1835 poem, Lucie: An Elegy.

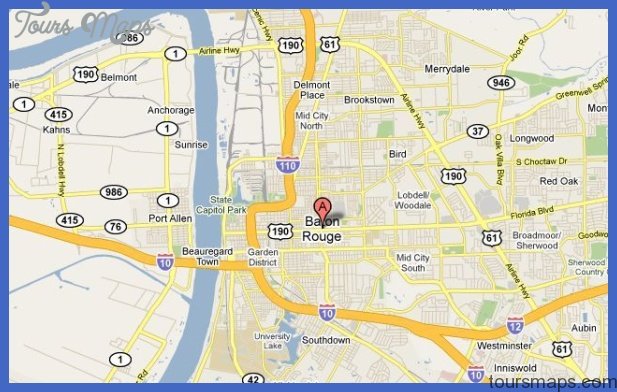

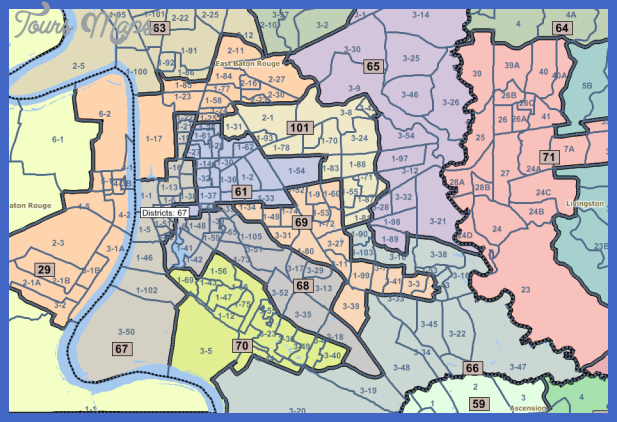

The Virginia Company sent out its first colonizing expedition of three ships under the leadership of John Smith in December 1606, instructing its colonists to maintain good relations with the local natives, then dominated by chief Powhatan. Baton Rouge Map The expedition, poorly prepared for the rigors of life in the New World, proved unsuccessful. Despite the public relations coup of the visit of Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas, a Christian convert, to London and the beginnings of tobacco cultivation, subsequent ventures also failed to prove economically rewarding. By the late 1610s, therefore, the company was increasingly troubled. The Virginia Company was not merely an economic organization. It also presented its mission in religious terms, sponsoring and publishing sermons given to meetings of shareholders and emphasizing the duty of converting natives and planting Protestant Christianity in North Country. (The great poet and preacher John Donne spoke before the company in 1622.) Unlike the sponsors of the early New England colonies, the Virginia Company, whose board included the archbishop of Canterbury and several bishops, was allied with the episcopal hierarchy of the Church of England. There was even an attempt to found a college at Henrico for the Christian education of Native Country men.

Baton Rouge Map Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World