ARCHITECT UNKNOWN

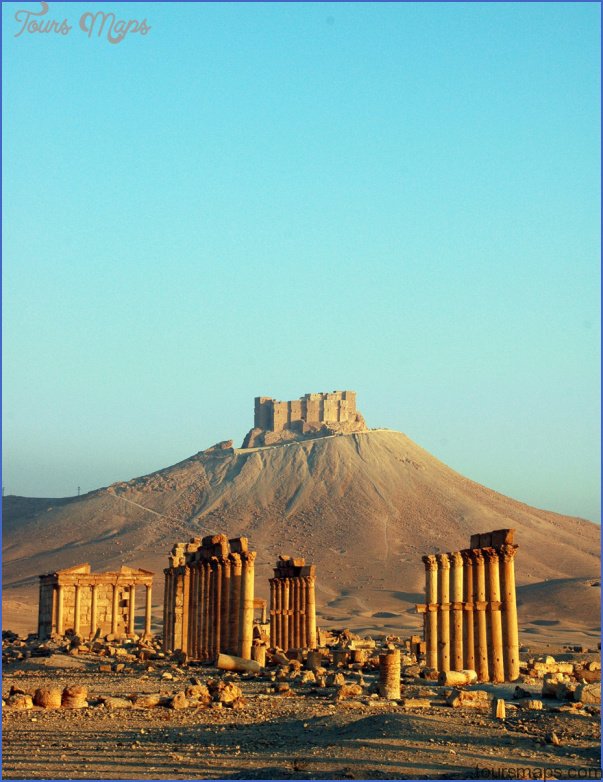

High on a rocky outcrop overlooking the Homs Pass in the Syrian desert stands the formidable Krak des Chevaliers, one of the finest and best preserved castles of the Middle Ages. Between the 11th and 13th centuries the rulers of Europe embarked on the Crusades, a series of unsuccessful attempts to recapture the Holy Land from the ruling Muslims, ostensibly to make Jerusalem safe for Christian pilgrims arriving there from the West. During these expeditions the Crusaders built a series of castles as military bases in areas that are now in Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan. Krak des Chevaliers was one of these strategic outposts, defending the Homs Pass on the main route from the Mediterranean Sea to the Holy Land.

There had been a castle on the site since about 1030. The Crusaders captured the stronghold on two separate occasions, finally handing it over in 1142 to the Knights

Hospitaller, a military, religious order set up to defend conquered lands in the Middle East and protect European pilgrims to Jerusalem. The Knights occupied the castle until 1271, when, after numerous sieges, it was finally captured by the Mamluk Sultan Baibars.

During their tenure, the Knights Hospitaller rebuilt the castle, extending it, strengthening the fortifications, and providing accommodation for a large force of up to 2,000 men. The resulting building is one of the best surviving examples of a medieval concentric castle, one that has two rings of defensive walls. These massive stone walls, the huge towers, and the castle’s lofty site, commanding views in every direction, made it almost impossible to take. T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), who wrote a study of Crusader castles, called Krak “perhaps the best preserved and most wholly admirable castle in the world.

IN CONTEXT

The first stone castles, built by the Normans in the 11th century, were based around a single large tower called a donjon. Later castle builders, especially the Crusaders, realized that even the largest donjon was vulnerable to attack, so they added more defensive features rings of outer walls, strong gatehouses, wall towers, as well as barbicans (outer fortifications) to make the castles more difficult to attack.

The builders understood the importance of choosing a good site, so they set their castles on hills and outcrops, from which defenders could see enemies approaching. Among the Crusaders military orders such as the Knights Hospitaller (the builders of Krak, Silifke, and Margat) and the Teutonic Knights (lords of Montfort) were especially skilled at castle building.

1 Kerak This well-defended, square-towered castle in Syria fell after an eight-month siege.

Visual tour

2 TALUS Many of Krak’s outer walls are thicker at the base than at the top, giving them a smooth, sloping profile called a talus (French for slope). This made them stronger, and less vulnerable to attack by weapons such as siege towers. Defenders could also hurl heavy rocks down the talus onto enemies below. These sometimes broke into sharp fragments, injuring attackers and impeding their progress.

Defending archers could shoot from the wall walk The warden’s tower provided accommodation for the Grand Master of the Hospitallers An aqueduct brought in fresh water from outside attack. Enemies had to penetrate both sets of walls to reach the living quarters within the castle.

This was an almost impossible task, especially as they came under attack from rows of archers who stood behind each set of walls, which gave them a huge range of fire. The protruding wall towers made it possible for the archers to shoot in different directions to aim at attackers at the base of the walls, for example.

2 TOWER OF THE KING’S DAUGHTER

This tower provided an excellent vantage point at one corner of the castle. The lower part of the tower, with its pointed Gothic arches, was built by the Crusaders. The castle’s later Mamluk occupiers built the upper section of the tower.

4 INNER WARD The courtyard, or inner ward, the best protected part of the castle, contained some of the most important buildings. These ranged from the Knights’ meeting hall, chapel, and apartments to those that were vital for the castle’s military success a vast building used to store supplies and a stable block that could accommodate up to 1,000 horses.

The talus protected the wall from siege weapons

3 GREAT HALL This imposing Gothic interior next to the cloister in the inner ward was probably used both as a meeting room and a reception room where the Master of the Hospitallers would receive visiting dignitaries. In European houses rooms like this often had a wooden roof. The Great Hall, however, has a stone vault, which helped protect the building from attack by fire but was also proof of the Knights’ superior social status.

The dark entrance passageway has a hairpin bend to impede attackers and make it easy for defenders to ambush them

1 VAULTED LOGGIA The Hospitallers built their castle in the Gothic style, with the pointed arches and stone vaults seen in European cathedrals (see pp.72-77). The finely carved vault ribs and the opening flanked by delicate shafts in areas like this vaulted passage indicate the high quality of the craftmanship. It is clear from such architectural details that Krak des Chevaliers was intended not only to protect its occupants, but also to reflect their social standing.

ON CONSTRUCTION

Almost everything about the castle, from its hilltop position to its tall towers, was designed to make the building strong and easy to defend. The concentric walls are up to 80ft (24m) tall and very thick some are said to be 100ft (30m) thick at the base. They have arrow slits in them, through which archers could take aim, and are topped with crenellations so defending archers could take cover between shots. At the top of many of the walls there are machicolations, protrusions that protected defenders while enabling them to drop missiles on enemies below. Anyone who managed to force an entry into the castle had to find his way along tortuous, winding passages, some of which had holes in the ceiling, through which defenders could shoot at him. Attackers stood little chance of survival.

1 Machicolations

The upper parts of some of the towers, such as the one on the left above, jut out, making it easier for defenders to drop rocks or pour boiling water through the machicolations onto attackers below.

CASTLE NEAR HOMS SYRIA Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit

- Coolest Countries in the World to Visit

- Travel to Santorini, Greece

- Map of Barbados – Holiday in Barbados