There are several others in more vivid shades of green: the wonderfully named and widespread Wompoo Fruit Dove of Australia and New Guinea has a bright green back, violet underparts and a red beak. Even so, the bird is apparently not easy to spot amongst the foliage of fruit trees. The White-crowned Pigeon of Central America and the West Indies is dark grey all over, almost black, with a white crown, while the gorgeous Namaqua Dove of the most arid African savannahs and semi-deserts in the Middle East, all pale grey and black with a long pointed tail, is such a delicate-looking bird in flight that I’ve sometimes assumed it’s something more like a parakeet.

There’s no point, of course, in my pretending that wild pigeons of all types are gorgeous creatures and admired by everyone. Many are not. Take, for instance, the super-abundant, stockily built Wood Pigeon found across the whole of Europe and east into the western part of Asia. Despised by farmers everywhere, Wood Pigeons delight in descending in huge flocks on to fields of grain, peas, beans and many others to devour as much of the crop as they can. Modern, intensive farming has indirectly and unintentionally encouraged them by growing extensive areas of such crops. And although numbers of Wood Pigeons with their plump breasts are shot for the table -and good eating they make too – the birds remain as abundant as ever.

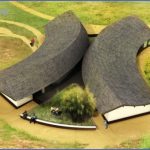

Kenya African Wildlife Foundation Travel Photo Gallery

In recent years, particularly in the UK, Wood Pigeons have quite suddenly realised that our gardens provide a very good food supply too, especially the bits of food that drop from the bird feeders that many gardeners put out to feed smaller garden birds, many of whom dislodge and scatter seeds and suet as they feed. For Wood Pigeons, the clumsier these smaller birds are, the more food that drops to the ground for them to hoover up. Combine that with seeds found naturally in many gardens, tall trees to roost in and no firecrackers or shotguns to molest them, and our gardens are a Wood Pigeon nirvana. We have them in our garden, though only in the last few years. With us they have established themselves like old friends. Our resident pair nest in a large cypress tree and the two of them waddle about, seemingly well fed, like a pair of very elderly, slightly corpulent pensioners on a day trip to the seaside.

Dove or pigeon, the names are really interchangeable, though many of the smaller, more demure species tend to be called doves; the plumper larger ones are nearly always pigeons. Of the 300 or so pigeon species in the world, 26 are endangered. That’s the result of habitat destruction (many are forest birds) and hunting (so many, especially the plumper ones, make a good meal) but also because some are confined to islands.

On Madeira, the popular tourist island off the northwest coast of Africa, the Trocaz Pigeon is to be found in its laurel forests but nowhere else in the world. Probably a descendent of a Wood Pigeon-like ancestor, it’s rather more colourful: grey and pink with a silvery neck patch. Isolated on Madeira it has evolved in its own way; today there might be as many as 10,000 there and they are quite easy to spot from vantage points on mountain slopes overlooking forested areas. The main problem is that the Madeiran laurel forests can sometimes be shrouded in mist. I was lucky; a clear day with good views from a mountain-top vantage point over extensive areas of forest and it wasn’t long before I saw one flying from one patch of forest to another. Then another. And within an hour I had seen several Trocaz Pigeons.

Much the same has happened on the Canary Islands south of Madeira where, on Tenerife, I recently waited – and waited – looking out over the laurel-forested Ruiz Gorge on its north coast until, on different occasions, I had glimpses of an occasional Laurel Pigeon and Bolle’s Laurel Pigeon fly past and dive into a tree irritatingly out of sight. These two have evolved in isolation (no pigeons fly large distances so they’re unlikely to make it to the African coast or from Tenerife to Madeira) and differ from each other and from the Trocaz too. Why two different pigeon species should have evolved on Tenerife, and just one on Madeira, no one knows. All three are protected; their forests are generally conserved, some are even being expanded by more tree planting and illegal hunting is seemingly minimal. So their future seems secure … albeit naturally restricted.

Times were very different for one much more famous bird; one that gave us a very commonly used saying but one that most people would never know was a pigeon. Long extinct, it too is ‘as dead as a Dodo’! I had researched the Dodo story when I was writing a chapter for Back from the Brink (Whittles, 2015) about the Mauritius Kestrel, a bird for which enormous conservation efforts had recovered it from the very brink of extinction. The same didn’t happen for its one-time fellow islander, the Dodo, also an inhabitant of Mauritius.

The curiously named Dodo was a metre-tall pigeon, probably brownish grey, and named perhaps after its pigeon-like call or from a mispronunciation of Portuguese or Dutch words such as dodoor for ‘sluggard’ but more probably from Dodaars which means either ‘fat-arse’ or ‘knot-arse, referring to the knot of feathers on its hind end. Whichever, neither origin is very complimentary! They lived only on this one large island. Contemporary drawings suggest that Dodos were plump, somewhat ungainly and covered in plenty of meat. But current thinking is that their ungainliness and obesity were exaggerated in contemporary drawings and descriptions though it’s not clear why. More importantly, they couldn’t fly and they nested on the ground, a rather fatal combination if there are hungry people about. Before humans started encroaching, there were probably no predators capable of killing them.

First mentioned by a Dutchman, Vice-Admiral Wybrand van Warwijck who visited the island in 1598, various accounts from the time give mixed reports about Dodo meat, some describing it as tasty, others as nasty and tough. Tasty or not, there are scattered reports of mass killings of Dodos for provisioning of ships for long voyages and, like many animals that evolved in isolation from significant predators, the Dodo was entirely fearless of humans. Combined with their inability to fly, it made the Dodo easy prey for sailors who clubbed them to death mercilessly. If they weren’t bludgeoned for food, their ground nests were almost certainly deprived of their eggs by animals such as rats, cats and pigs introduced by Mauritius’s early settlers. At the same time, people started felling the island’s forests where the Dodos nested and fed.

The last widely accepted record of a Dodo sighting is the 1662 report by shipwrecked mariner Volkert Evertsz of the Dutch ship Arnhem who described birds caught on a small islet off Mauritius. There’s also a description from around 1680 by Benjamin Harry, chief mate on the Berkley Castle. And a sighting was reported in the hunting records of Isaac Johannes Lamotius in 1688. Regardless, the Dodo must have been rare for some time before that and it’s unlikely that any survived past the last decades of the 17th century, just a century after it was discovered.

For a long time this rather odd-looking pigeon was forgotten. Not though by Lewis Carroll who immortalised it in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). The Dodo of his stories is supposedly a caricature of the author whose real name was Charles Dodgson. A popular but unsubstantiated belief is that Dodgson chose it because of his stammer, and thus would accidentally introduce himself as ‘Do-do-Dodgson’.

I have another interest in this story too. For the last 30 or more years I have lived near Llandudno, one of the most pleasant and attractive coastal resort towns in Britain. Llandudno was the holiday destination of the real Alice in Wonderland, Alice Liddell, the girl who inspired Lewis Carroll and on whom he based Alice in Wonderland. She first came to the town with her family on holiday in 1861 aged eight. Carroll became a close friend of the family and it is believed by some that it was Alice’s exploits in Llandudno that provided inspiration for his Alice blogs.

With the popularity of the blog, the Dodo became a well-known and easily recognisable icon of extinction. But probably hardly anyone today would ever guess that the hapless Dodo was a pigeon.

Our alarm buzzed at 4 a.m. The night’s darkness was just giving way to a distant slit of light and in half an hour came the knock on the door. Michal Krzysiak was distinctly brighter and more cheery than my wife and I. A well-built vet with excellent English and working for the Bialowieza National Park, we had arranged for him to take us on a dawn tour searching for Europe’s largest land animal, the European Bison, cousin of the arguably better known American Buffalo.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

- Anniston Map

- Wildlife Travel Guide

- Wildlife Travel To Alonissos

- National Wildlife Travel