According to Florence of Worcester, not as you might imagine a female but actually a well-educated male monk who died in 1118, the forest was known before the Conquest as Ytene, its early Anglo Saxon name. It was first recorded as ‘Nova Foresta’ in the Domesday Book in 1086 where a section devoted to it also mentions the town of Southampton, today the largest conurbation near its edge. It is the only forest that the blog describes in detail.

About 90% of the New Forest is still owned by the Crown and, since 2005, the bulk of it is a national park. The Forest – in reality a mix of heaths, bogs, what are locally called ‘lawns’ (grazed grasslands), broadleaved woodland and plantations of conifers – probably has more protective designations than any other place in Britain.

But what makes the New Forest equally special for me is its cultural inheritance and the long history of its traditions of land use dating back to the Conqueror’s times. Without those traditions the Forest wouldn’t be what it is: albeit a managed landscape but much of it uncompromisingly wild, a place out of time in the modern world, a contrast with the hubbub of modern urban Britain on its doorstep but strangely distant from it.

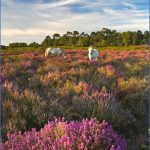

The most important element of that is the long established right of common grazing, a right which is attached to certain properties in the forest. Anyone holding such rights can graze ‘ponies, cattle, donkeys and mules’ on the open areas of grassland and heath. About 5,000 animals graze the forest, more ponies than cattle. Without controlled levels of grazing, the heaths and grasslands would slowly develop into scrub – gorse, bracken, bramble and small trees – eventually changing these habitats back into forest. It is the long established mix of habitats, rather than any one of them singly, that make it such a special place for wildlife and which conveys its enormous scenic attraction.

There is also a right of ‘common of mast, the right to turn out pigs in autumn to devour acorns and beechmast that falls from the woodland trees. Pigs devour both and also provide a useful service because acorns are poisonous to cattle and ponies. In the past, large numbers of pigs were put out in autumn but today that has declined to maybe a few hundred. Some property owners have other common right too; estovers refers to the collection of defined amounts of firewood while rights to dig lime-rich clay as a soil fertilizer and to dig turves of peat for heating are apparently not used these days.

All of this commoning is overseen by the New Forest Verderers, originally part of the ancient judicial and administrative hierarchy of the vast areas of Royal Forests set aside by William the Conqueror. The title ‘Verderer’ comes from the Norman word vert meaning green and referring to woodland. The Verderers met regularly as a Court to adjudicate over disputes – they still do today – and their powers are widely drawn. The Official Verderer is appointed by the Queen; the others are a mix of appointed and locally elected Members. In effect, the Verderers are the guardians of the commoners, of their common rights and of the Forest landscape.

New Forest Guide for Tourist Photo Gallery

Much of the day-to-day management of the livestock grazing in the Forest is the responsibility of five Agisters who are employed by the Verderers, each one allocated a defined part of the Forest. Their role is ancient and their title derives from ‘taking cattle to graze in exchange for payment’. Most are commoners themselves, they are expert horsemen and they have an intimate knowledge of the Forest. They ensure that the commoners keep their stock in good condition and they enforce byelaws made by the Verderers, they organise the annual autumn roundup and marking of the Forest ponies, and they get called out to road accidents involving livestock (which many people claim are too commonplace) or to incidents such as ponies getting stuck in a bog, which – if our experience is typical – could also be quite frequent.

Neil McCulloch, the landlord of the Royal Oak at Fritham, is one of the 400 or so New Forest commoners with grazing rights over its open land. He’s fairly typical; most have a job in addition to their commoning. But putting out livestock to graze and checking their condition isn’t the same as it was before tourists began to visit the New Forest. Today it can be a frustrating business. ‘Calling it a national park is good for tourism. Most hotels, cafes and B&Bs say the same. It attracts more people’ said McCulloch when I interviewed him a few years ago for a feature I wrote about the Forest for The Guardian.

‘We’re a traditional freehouse catering mainly for walkers, cyclists and people from nearby campsites. Without a good trade, we couldn’t survive as a pub,’ he said to me. ‘But I’m torn. As a commoner I don’t want to see more traffic on the roads. I graze cattle and pigs out in the Forest. In summer you can’t get around to move or check livestock because there’s so much congestion on all the roads. It’s already a big problem here, and it’s getting worse,’ he added.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

- Anniston Map

- Wildlife Travel Guide

- Wildlife Travel To Alonissos

- National Wildlife Travel