Ftnding the Unicorn

Sitting, cross-legged as always, on the patterned, carmine red rugs in the Bedu tent, I was listening to the Arabic banter. Abdulrahman and Mubarak, dressed in their traditional long white thobes with red and white check ghutras (headscarves), were having a lively exchange about the virtues, or otherwise, of having a wife. It was time, Abdulrahman said, that young Mubarak should start thinking of marriage. Their laughter was infectious.

Through the open, hearth-end of the tent a mesmerising, beacon-bright halfmoon hung in the inky-black night sky. Walid, the camp’s ever-smiling Pakistani cook, dressed for the long evenings in his brown-striped kaftan, came in with more dates and yet another silver-coloured, long-spouted pot of bitter, cardamom-rich Arabic coffee. He placed it carefully on the hearth, in reality just a scrape in the sand where burnt wood ash still retained enough heat to keep the refreshing brew warm. Very soon, wafts of wood smoke mixed with the heady aroma of cardamom began to scent the tent with an almost hypnotic air.

Wildlife Travel To Rub’al-Khali Photo Gallery

I was in a camp on the western fringes of the Empty Quarter, an uninhabited desert the size of France – the Rub’al-Khali made famous by the explorer, Wilfred Thesiger (1910-2003). It all seemed so reminiscent of a biblical scene, as if a robed itinerant preacher might come by any minute for a little food on his travels. Except that a couple of loaded AK47s lay casually on the carpeted floor of the tent, ready for use if they were needed, and a reminder that the Arab rangers had a potentially dangerous modern day job to do.

I got talking to Abu Ali, the Head Ranger whose home was at Sharurah, further south near the Yemen border. In stilted English he was able to tell me that his father, a local Bedu of the Sayari tribe who knew the Empty Quarter and how easy it was to die in its parched sands, had seen some Arabian Oryx and Sand Gazelles half a century ago. He knew that they were perched then precariously on the very cusp of extinction. Now Abu Ali was helping to return both animals to this magnificent sand desert where they belonged. He is one of the small Saudi team here whose work it is to help monitor the oryx and, if necessary, to use those AK47s to see off – or worse – any poachers that try to kill or capture them.

And it was these fabled animals, especially the oryx – thought to be the origin of the unicorn myth – that I had come to see. The reintroduction of the Arabian Oryx remains one of the world’s most successful reintroductions of an animal once extinct in the wild and now breeding again in the core of its former range. Strikingly beautiful, salt-white oryx had roamed the Empty Quarter and a much larger area of the Middle East until the last one was killed five decades ago. Now, this enigmatic animal was back in one of the harshest, most unforgiving places on earth and seemingly doing very well. In exchange for writing a feature about their recovery for Kuwait Airways’ in-flight magazine, Al-Buraq, a colleague and I were given free return tickets from London via Kuwait City to Jeddah in Saudi Arabia. It turned out to be a brilliant trip organised through Saudi Government channels.

We had arrived at the camp, a set of portacabins and tents in the Uruq Bani Ma’arid Reserve in the west of the Rub’al-Khali, in darkness, the kind of night-time darkness now hardly ever experienced in Britain and not even lit by a scatter of stars. The drive from Taif, inland from Jeddah, had been a long one, finished off by many kilometres of rough, stony track from the nearest metalled road up to the Uruq camp. The camp, like most Saudi installations such as roadside garages, oil production plants or roadside cafes, was brightly lit; it would have stood out as a beacon for huge distances all around in this enveloping darkness except that it was surrounded, I assumed, by mountain slopes. We didn’t see it until we were maybe a kilometre away.

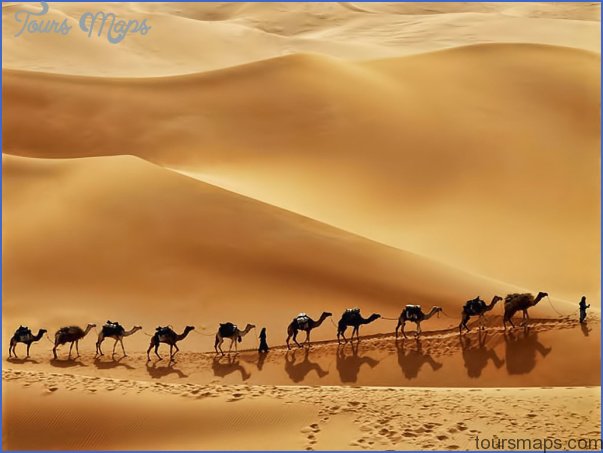

In the naturally bright light of the following morning, what I had assumed to be rocky mountainsides surrounding us turned out to be huge, sculpted, orange-pink sand dunes, the most fabulous I have ever seen, their slopes smoothed into perfect, voluptuous curves by the desert wind. For a while I did nothing but stare at their elemental beauty.

Later that first morning I was out in a 4WD heading east with Maartin Strauss, a South African mammal expert and Eric Bedin, a French biologist, who were monitoring oryx for the Saudi Wildlife Commission which has reintroduced the animals here in the Empty Quarter. We were driving along heat-hazed, almost white gravel plains, folded pink-orange sand dunes, some of them huge, on either side. In the searing heat, by mid-afternoon I had begun to wonder how any animal could possibly exist in such an inhospitable place, let alone thrive, give birth and raise young. There were no animals in sight.

Then quite suddenly, scanning ahead with binoculars, Maartin Strauss spotted them. Some distant, fuzzy white shapes and a flurry of orange-ochre sand were all that was obvious to me as I searched the vast, heat-shimmering plain. Could these distant, hazy objects possibly be the legendary Arabian Oryx? ‘Seven oryx. All adults I think. They’re grazing on some bushes. They look pretty settled; I don’t think they’re going to move on for a while anyway. We’ll try and get closer,’ commented Maartin, as we drove further into the sands to get a better, and clearer, view of the distant white spots.

Eventually we got within a kilometre of them, seven oryx watching our every move. The size of large deer, their gorgeous deep, black eyes contrasted with their bleached-white coats and their enormous pairs of horns caught the bright sun like skyward-pointing rapiers. When these animals stand sideways, it can seem as if they have only one horn, the probable origin of the unicorn myth. They were even more magnificent than I had contemplated.

‘Four of them are tagged with collars’ whispered Maartin as we sat huddled in the Jeep, binoculars held handcuff-tight, the sweltering heat building by the minute. ‘The numbers printed on their tags means that these four are released animals. I can date the releases from the tag numbers when we’re back at camp tonight. The other three must have been born out here in the wild,’ he added with obvious pleasure. We left them on the sun-baked, bleached white gravel, eloquent testimony to their ability to live out their lives in one of the most arid places imaginable. Here, in the scorching heat of summer where temperatures in the sun can easily reach 50°C, a human can barely survive for eight hours without water.

The smallest of the four species of oryx in the world, Arabian Oryx stand about 1 m high at the shoulder, females weigh up to 80 kg; males, up to 100 kg. Apart from this difference in weight, and the fact that females usually have longer horns than males, the sexes are very similar and it’s very difficult to distinguish them in the field. I certainly couldn’t. Their coats are an almost luminous white to help with camouflage and to reflect away the sun’s heat, their undersides and legs dark brown, and they have black stripes where the head meets the neck, on the forehead, on the nose and going from the horns down the face to the mouth. Because they have hooves that are splayed and shovel-like, oryx can walk effortlessly on sand dunes. Fast runners, their newborn calves are able to trot with the herd almost immediately after birth.

I hadn’t realised how visually impressive their horns really are; long, straight or slightly back-curved, they have a kind of barley-twist pattern along their length and can be up to 75 cm long. Viewed sideways or from a distance, an oryx looks something like a horse with a single horn (although, in the oryx’s case, the ‘horn’ projects backwards not forwards as in the classic unicorn). Nevertheless, early travellers in Arabia could quite easily have derived and embellished the tale of the unicorn from these animals.

And it was these exquisite horns that made them too tempting as a prized game trophy. The demise of the Arabian Oryx became a virtual certainty when Arabian princes and newly oil-rich Arabs in Jeeps and big American cars fitted with sand tyres started making incursions into the Rub’al-Khali in the 1930s and 1940s. Armed with more powerful rifles, even machine guns, oryx hunts grew in size, many of them employing animal-exhausting chases from 4WDs, even helicopters, and some were reported to use as many as 300 vehicles. It rapidly became a slaughter on an epic scale; many of these people didn’t even want the horns, they simply wanted to chase and kill wild animals. Their carcasses were left to rot where they were shot.

The desert-living, nomadic Bedu had always hunted oryx. After all, they would provide a much more bountiful supply of meat than a desert hare and add variety to an otherwise torrid diet. Their leather hides were important too. But, armed only with primitive rifles until perhaps the 1920s, they would probably have been able to kill very few. By the 1960s, fewer than 100 oryx were thought to survive in the wild, almost all of them here in the Rub’al-Khali. A couple more raiding parties and there would have been none. And that’s when the forward-looking Fauna and Flora Preservation Society, FFPS (now Fauna and Flora International, FFI), with World Wildlife Fund cash, decided that the only way to guarantee their survival was to capture some animals and set up a captive breeding population before the last wild oryx were hunted down. Time was not on their side.

And FFPS were proved right. The last wild oryx had been spotted in 1972 and they were either killed or captured a few weeks later. Bred in captivity at the Phoenix Zoo in Arizona and some other centres, the first oryx were reintroduced into the Omani sector of the Rub’al-Khali in 1982. And they were initially successful. By 1995, they numbered around 280. The scheme was looking really positive. Then problems surfaced once more. Poaching resumed and some oryx were illegally captured for sale to be kept as live animals outside the country. A downward spiral started yet again. By 1999 there were 85 oryx left and a decision was taken to capture them and move them into a large fenced enclosure (at 27,000 km2 still a vast area by European standards) where they could be protected. Even protecting them in that so-called ‘Arabian Oryx Sanctuary’ proved difficult. Personal greed apparently knew no bounds when it came to capturing these magnificent animals to decorate the grounds of some rich Middle Eastern or overseas estate.

Thankfully, here in the Saudi Arabian part of the Rub’al-Khali, oryx reintroduction has been much more successful. Between 1995 and 2002, a total of 174 animals, in a large number of social groups, had been released into the Uruq Bani Ma’arid Reserve, in reality a large section of the western side of the Empty Quarter. Now there are at least 200 oryx here and their breeding is increasingly successful. There are other reintroduced populations; in the UAE, Jordan and in Israel, giving a total in 2011 of about 1,000 wild oryx. Others are kept in ‘captivity’, in practice mainly in large areas of suitable desert habitat where they roam freely.

Here in the Uruq Bani Ma’arid Reserve there is no surrounding fence so it’s open to the bewildering expanses of the arid Rub’al-Khali to the east. It’s difficult to comprehend its magnitude; peering eastwards in the strong sunlight, the dunes, folded one into another, seem to go on forever. And that’s not too much of an exaggeration; the Empty Quarter measures about 1,000 km west to east, the same distance as London to Prague. Uruq was selected for the reintroduction because it contains greater biological diversity than any other part of the Empty Quarter with vegetated wadis, gravel plains, and inter-dune corridors. And oryx had historically been present here.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

- Anniston Map

- Wildlife Travel Guide

- Wildlife Travel To Alonissos

- National Wildlife Travel