Seeing and hearing Musical museums attract the music lover whose main experience of music is as a listener. If visitors are lucky, they will discover something to give added meaning to their pleasure in music. It may be that the museum is connected with familiar or favourite works, or perhaps that the room in which the composer chose to work, the view from his study window, the singing of birds or the rustling of leaves, may offer some lingering resonance with the music.

Anyone who sings or plays an instrument is accustomed to reading from clearly printed modern editions. It may come as a surprise to see an autograph manuscript, betraying as so many do the signs of the struggle that accompanied the written manifestation of a composition; another may seem to have been set down with evident ease. To judge by their manuscripts, the creative process for Beethoven was an agonizing effort, for Mozart seemingly routine. Whether a manuscript on display is in fact an autograph or a reproduction, the essential connection can still be made between the ‘object’ and its creative context.

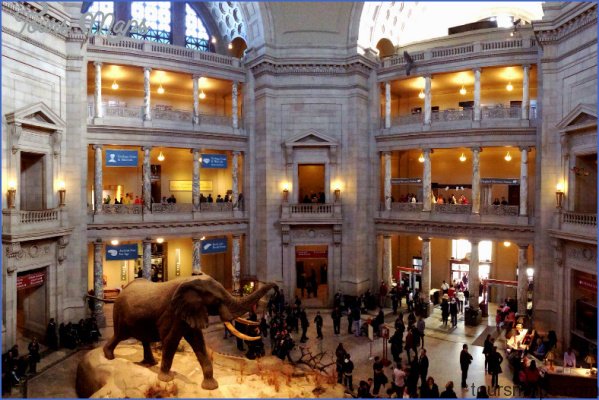

BEST MUSEUMS IN NEW YORK Photo Gallery

For those lucky enough or sufficiently trained to be able to hear music as they read it, that connection can be immediate. A visitor knowing a work on display may note differences between what can be seen and what is familiar from other copies, and that may increase the awareness of how music is transmitted, adjusted and reinterpreted. For others, the state of the manuscript, the paper on which the composer wrote, the annotations he and perhaps others made later, will in themselves command attention. Signatures on scores may reveal clues to the history and sometime ownership of a particular copy, as too may the bindings or annotations on the title-page or the first page of the music. For other visitors, the composer’s calligraphy – often a very personal shorthand – will be interesting as art representing sound, and indicative of the composer’s age, his state of mind and even his health, not to say his creative processes. Notated music, of course, is only a visual analogue of the imagined sound, so recordings (especially those involving the composer himself) represent a significant part of the experience of connecting the composition to a specific environment. Facsimiles of manuscripts, modern editions and CDs of music associated with the composer’s residence in a house or a region are often available in museum shops.

The sound of music, whether as a background to a personal tour or emanating from listening stations, is an obvious adjunct to a composer museum. Some of the most modern museums incorporate visual projections and video presentations, often including historical film footage, into the visitor’s experience. Audio-visual interpretation can be central to the success of these commemorations as visitor attractions, especially when the house or room site lacks a significant collection to display. The birthplace of Handel in Halle provides a recorded tour in any one of several languages. The birthplace of Satie in Honfleur explores the eccentricities of the composer’s personality through a series of tableaux that rely on portable sound systems to convey music and commentary, spoken as if by Satie himself, and enhanced by lighting and projections, theatrical props and video installations. An increasing number of the larger composer museums make available personal sound systems, usually hand-held, which interact with individual displays; among them are the Mozart Wohnhaus in Salzburg, the Berlioz birthplace in La Cote-Saint-Andre, and the museums to Smetana in Prague, to Wagner in Bayreuth and to Nielsen in Odense. Video presentations can serve efficiently to summarize the life of a composer as well as to introduce visitors to the museum and to particular artefacts on display; these are usually shown at regular intervals or at pre-arranged times, and sometimes in a choice of languages. The exceptional use of live performers and costumed interpreters to represent the composer and his circle, especially when the performances are of a high standard, may be extremely effective: this is done at the Tchaikovsky birthplace at Votkinsk, with readings (in Russian, but the visitor is handed a summary in other languages) based on family letters of the time.

The impact of context In the 1990s the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien renovated all eight of their Musikergedenkstatten. In appointing the Viennese-born architect Elsa Prochazka to redesign the exhibitions, they stepped away from individualized period re-creation in favour of a corporate modern design image. The museums – one each to Haydn, Mozart and Johann Strauss, two to Schubert and three to Beethoven – all have the same distinctive museum furniture, with tall stands and much polished wood, though with different colours of wood stain (if it is kiwi green, for example, you know you are in a Beethoven museum): the sense of a dwelling place belonging to a particular era and a particular person is eliminated. This would seem to represent a design philosophy that favours an uncluttered, objective uniformity even if at the expense of atmosphere, individuality and re-creation; the cynical visitor may wonder why such a museum needs to be in the composer’s living-space at all. Perhaps the displays devoted to the genius loci are planned as a gesture of compensation. Such an approach might well focus attention on the items displayed were it not that the cabinet mechanisms, in the interest of having the visitor ‘interact’ with the displays, require the lifting of spring-loaded wooden covers to reveal the captions. This is surely tiresome and discouraging; there is no way of taking in display and caption at a glance. It is difficult to see in what sense the memory of the composer is served or the connection with his music enhanced by this gratuitous additional degree of separation between visitor and object.

The interpretation of its collection is part of any museum’s present-day raison d’etre. The most exciting collections carry within them evidence of past contexts. The legacy of Robert and Clara Schumann in Zwickau illustrates this most movingly. Just as their marriage and household diaries offer unparalleled glimpses of a loving, collaborative and fruitful union, so too does their copy of the Beethoven piano sonatas, bearing annotations in both their hands and the annotations by Robert and by Mendelssohn in a copy of Bach’s chorale preludes speak to the two men’s collegial friendship (and perhaps their different thoughts on Bach interpretation). In the Donizetti and Bellini museums, the rich collections of musical manuscripts on display include tantalizing glimpses of operas and sketches for uncompleted works. In Prague, the comprehensive survey of Smetana’s music includes drafts, versions and music omitted from the final scores as well as evidence of the composer’s involvement in the early productions of his operas, limned out in extracts from his diaries.

Many museum displays focus on the music of a particular period of a composer’s life, coinciding with his period of residence in the building. That is the case with most of the Viennese museums. It is a policy often pursued when a composer is commemorated in two or more museums, which can represent different phases of his creative life. The museums at Graupa and Lucerne, for example, largely limit their displays to the periods in which Wagner lived in each place.

Presenting music An assumption underlying most museum displays is that visitors should not be expected to have much practical knowledge of music. Displays installed during the past two decades suggest that people are rather more interested in (and better informed about) history, social history in particular, to the extent that the presentation of the ‘house’ as ‘home’ takes precedence over the coverage of music. This is in part a reflection of the interest that musicologists have taken since the 1970s in the wider context for music. It is also indicative of how difficult the display of music as such actually is, calling for specialist musical knowledge as well as the normal skills of museum professionals.

Faute de mieux, the objects of music, especially manuscripts and editions, are apt to be treated as if they were minor works of art. Few would dispute that written or printed music is not usually in itself a thing of great beauty, except perhaps in a calligraphic or typographical sense. There are of course exceptions, such as illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, or in a minor way the elegant Rococo title-pages of the 18th century and the Art Nouveau ones of the late 19th. The external, ‘artistic’ quality of an object is one issue; its internal or inherent value, in the case of music, quite another. The presentation vis-a-vis music represents yet a third. Visitors are usually provided with only minimal clues towards the interpretation of music on display, through labelling and the sequence and groupings in which exhibits are arranged. It is rare for attention to be drawn to particular passages that might be of special interest, or to be encouraged to observe evidence of the compositional process, as for example when making comparisons between versions of a work.

Virtually all museum displays include examples of the composer’s manuscripts, elucidated in captions, sometimes in more than one language. Occasionally originals are shown, but usually only for limited periods because of the effect of light on paper and ink and the damage to bindings from leaving volumes open too long at the same place. Facsimiles are increasingly being substituted; the techniques for their production and the replication of period paper are now so refined that it is often almost impossible for the visitor to differentiate them from the original, especially when looking through glass.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit