‘It takes the down from about 65 nests to produce a kilo of finally cleaned and sterilised down,’ Thorvaldur tells me. ‘We’ve been collecting down since 1992, the year after we bought the islands. We’re here for about three weeks in June to do the collecting and the previous owners probably did the same every summer, right back to the 1700s or before. We have five inflatable boats so we can split into small groups to get to the different islands’ he says. Our conversation is occasionally interrupted by Thorvaldur’s need to tip out a little brown tobacco snuff on to the back of his hand and then sniff it up each nostril in turn. Then we pause for the impending sneeze caused by said snuff and a couple of wipes with a handkerchief before we can continue our conversation. Some might regard it as a bad habit. There certainly are far worse.

Small, fine down feathers form a layer underneath the visible outer feathers and insulate a bird’s body. But on a female eider’s chest, the down feathers become loose at breeding time, which enables them to pluck them off in their thousands and line their nests, shallow depressions in small grassy hollows.

Being PC has clearly not entered the thinking of a male eider. They are, instead, notorious for their lack of contribution to the whole nest building, egg incubation and chick rearing process. They simply chill out, relaxing in the shallow waters around the edges of the islands. Once they have copulated with their chosen female, that’s it; job done for another year. No responsibilities and no further work. But what these work-shy drakes are good at is making a far-carrying, crooning call to their plainer looking females, just to keep in touch and, maybe, to reassure their nest-confined mate that all is well around and about. It’s a haunting sound that carries on the breeze through the day and, now in midsummer when there is no darkness, through the night too.

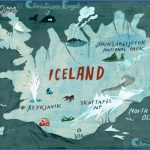

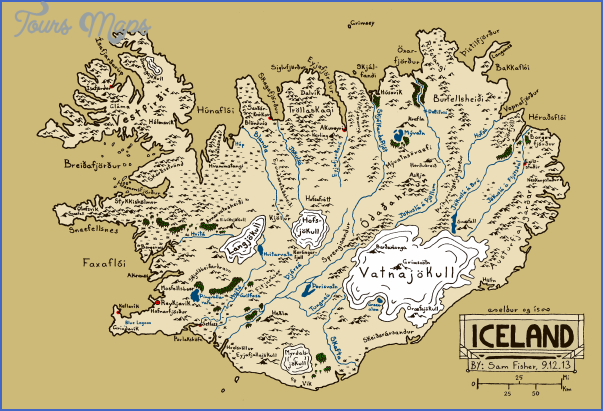

Iceland Map Photo Gallery

The first day of my eiderdown collecting is sunny with only a gentle breeze, though I hesitate to claim that it’s warm. Suffice it to say that it is about average for a June day on Iceland’s coast. Three of us – Thorvaldur, 16-year-old Fannar Mar Andresson, the son of one of Thorvaldur’s friends, and me – set off from Hvallatur at low tide. We paddle through the shallow seawater across barnacle-encrusted black rocks to nearby Tresey, a much smaller mound of an island, its slopes grassy and well grown enough to hide more eider nests than I would ever have guessed could be hidden there. Mottled brown and sitting tight on her four greenish eggs, the first female eider we encounter suddenly flies off with a clatter of her wings when we are no more than a couple of metres from her nest, a grassy scrape between some rocks lined with a large bunch of minute and incredibly soft brown feathers. It’s my first look at eiderdown in the nest.

I pick some up; it’s so incredibly soft and warm. And more than that, it is virtually weightless. A small handful of this precious commodity seems to weigh nothing. Squeeze it into a ball and it springs back immediately after I release my hand pressure.

That is why, Thorvaldur assures me, an eider duvet is so insulating and retains its shape.

‘We remove the eggs carefully, take out all the down, then replace the eggs after filling the nest with dry hay. We cut and dry the hay ourselves on the island. Studies done here have shown that the hay insulates the eggs just as well and the eggs hatch normally,’ says Thorvaldur as he deposits our first handful of dry, brown down inside the hessian bag he carries.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

- Anniston Map

- Wildlife Travel Guide

- Wildlife Travel To Alonissos

- National Wildlife Travel