The Centennial Valley WEST YELLOWSTONE TO MONIDA Estimated length: 74 miles estimated time: 3 to 5 hours Highlights: Wildlife viewing, exceptional birding, hiking, Red Rock Pass, Fountain of the Missouri, Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, Elk Lake Resort, Lakeview Getting there: From I-90, there are several ways to reach the Centennial Valley all of them scenic. Coming from Butte on I-15, make any necessary stops for gas, food, or lodging in Dillon, Lima, or Dell before leaving the freeway at Monida, the last exit before Idaho and little more than a dilapidated collection of empty buildings. Drive through the remnants of this former railroad town and follow the signs for Lakeview and the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, both 28 gravel miles ahead. This is the west end of the valley and the road less traveled.

To begin at the east end, take US 191 from Bozeman through the scenic Gallatin Canyon and northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park to the community of West Yellowstone.

Continue west on US 20 over the Continental Divide into Idaho. At the junction of US 20 and ID 87, turn right and drive along the north shore of Henrys Lake. Turn left on FS 055 around the west end of the lake, then veer right on Red Rock Pass Road. In West Yellowstone, stock up on any necessary goodies and fuel up because you won’t see a single backcountry store until you’re on I-15.

If you’re coming down US 287 from Three Forks, you can shave a few miles by turning right on MT 87 across the Madison River and heading over Raynolds Pass into Idaho, where the road becomes ID 87. You’ll quickly see Henrys Lake; turn right on FS 055. The entire Centennial Valley route is on gravel and dirt, and the shaded east side of Red Rock Pass can get especially soupy after spring runoff or a hard rainstorm A high-clearance and/or four-wheel-drive vehicle is recommended, though unnecessary when conditions are dry.

OVERVIEW

Ask most Montana residents with an appreciation for wild country where they go to see and feel the open range of 150 years ago, and chances are good they’ll take a reverent breath and utter, the Centennial Valley. It’s so remote, even for Montana, that you must leave the state to get there from the east end. Upon the second of two ascents to the Continental Divide, including a brief foray past log vacation homes on Idaho’s Henrys Lake, visitors soon realize why Montanans have such high regard for this place.

The Centennial is a broad, largely unscarred and level plain with lakes, marshes, sagebrush, a handful of sprawling cattle ranches, one tiny unincorporated community (Lakeview, no services), and the Red Rock River meandering through its heart. It is buffered by the burly shoulders of the Centennial Mountains to the south and the southern tips of the rugged Snowcrests, Blacktails, and Gravellys to the north. It’s a place where winged creatures outnumber bipeds by about 10,000 to one. Depending on your mindset, an aura of serenity or loneliness exists here, and there is a palpable separation from the modern world. Also making the Centennial extraordinary: The 385,000-acre valley and mountain range of the same name run east-west, an oddity in the Northern Rockies. It is thus a critical wildlife corridor between Greater Yellowstone which is essentially an ecological island amid a sea of increasing development and the wilds of central Idaho and Montana’s Glacier region. Birders will be in avian heaven in the 44,963-acre Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, which features more than 240 species. The refuge was created in 1935 because of its importance as a stopover for migratory waterfowl such as the endangered trumpeter swan and prehistoric-sounding sandhill crane. Almost all the native wildlife from 200 years ago still roam the valley the notable exception being bison

It’s difficult to imagine, especially if you enter from the east side, that the Centennial was once relatively heavily traveled and occupied. Before E. H. Harriman of the Union Pacific Railroad punched his Oregon Short Line through the mountains from Ashton, Idaho, to West Yellowstone in 1908, one of the primary routes to Yellowstone National Park was through the Centennial. Passengers on the Northern Pacific Railroad disembarked at Monida and took the Centennial Stage to West Yellowstone, exchanging horses every 15 miles. Former president Teddy Roosevelt, perhaps the father of American conservation, reportedly took the journey once. Another ex-president, Harry S. Truman, shook the hands of locals at a train stop in Monida, now a virtual ghost town. Lakeview was a base for Utah & Northern Railroad workers who commuted to where the main Northern Pacific line crosses Monida Pass which draws its name from the first three letters of both states.

The Centennial Valley, named by early cattle rancher Rachael Orr, who first saw the valley during America’s centennial in 1876, has been preserved for many reasons, foremost among them its remoteness and an unforgiving climate. The valley also has been spared mineral exploration and rapacious logging for similar reasons. And the fifteen multigenerational ranch families that own 90 percent of the 100,000 acres of private land in the Centennial have cultivated a conservation ethic. The ranchers, the federal Bureau of Land Management, and The Nature Conservancy which owns much of the remaining 10 percent of private land have forged a partnership dedicated to preserving the Centennial’s wide-open spaces and ranching legacy. Their shared vision has fostered a balance between utilitarian use of the land and preservation of wildlife habitat, so future generations can drive the bumpy 51 miles and see some of our most iconic critters, including grizzly bears, wolves, Shiras moose, bighorn sheep, eagles, snipe, and trumpeter swans.

HITTING THE ROAD

To fully appreciate the lack of intrusion into this wonderland, start your journey at West Yellowstone (pop. 1,321), a crowded metropolis compared to the rest of the route. Once a getaway for Las Vegas hoteliers and a few of their sordid friends which explains the oddly named Desert Inn Motel, for example this outpost enveloped by lodgepole pines and hard on the western boundary of Yellowstone National Park is working to transform its rubber-tomahawk souvenir-shop image into one of more sophistication and diversity. For nearly five decades, its winter existence has revolved around snowmobiling, and its summer season has been dominated by families in station wagons and minivans, all eager to see Old Faithful. If you’re looking for activities other than what the natural world has to offer, the IMAX Theater (406-646-4100) and Grizzly & Wolf Discovery Center (406-646-7001/800-257-2570), adjacent to each other near the edge of town, will fill the bill. If you miss seeing some of the wildlife in the park, catch them in living color at the Discovery Center, where the bears don’t hibernate because they have a year-round source of food. West Yellowstone has plenty of lodging and dining during the summer, but many businesses close during the winter and shoulder seasons.

As you head west from West, look closely at the mountain range in full view straight ahead. With a little imagination, it’s easy to see why the 10,080-foot peak along the Continental Divide is called Lionhead. You’ll soon be over Targhee Pass into Idaho. Though this is a book about Montana, we suggest spending a day on Henrys Lake trolling for legendary trophy trout. The sweeping valley before you is the key wildlife connector between Yellowstone and the Centennial. To the southwest, you’ll see what looks like a giant golf ball on top of a peak. This is a radio tower atop Sawtelle Mountain, the eastern terminus of the Centennials. If you turn right on ID 87, you’ll meet up with FS 055 in about 6 miles.

If you continue south on US 20 toward Island Park, Idaho, you can turn right on FS 053 in 6 miles. Either way, the two gravel Forest Service roads meet just off the southwest corner of Henrys Lake, about 3.5 miles shy of Red Rock Pass. Afer passing a few log homes, the road ascends through aspens to the modest pass and a welcome step back in time.

Red Rock Pass is more of a long and gradual bump in the road than an actual pass. After a brief descent through fir and pine, the Centennial’s wide world of wonder begins to unfurl, with an endless horizon between five mountain ranges. There are no homes and few power lines to mar the view only a few fence lines and an occasional mailbox marking a hidden ranch house. Immediately to the south are the towering Centennials. Tucked deep into the forest, Brower Spring, aka the Fountain of the Missouri, trickles from the flanks of Mount Jefferson at 9,030 feet in elevation, and its waters begin a 2,530-mile journey to their meeting with the Mississippi River in St. Louis. No waters anywhere in the United States travel farther. It’s a strenuous hike into wild country, but if you’re fit and determined, you’ll be one of few Americans to say they have sipped from the uppermost Missouri headwaters, which are marked by a pile of rocks; an easier trail comes from Sawtelle Peak. Park at the Hell Roaring Creek Trailhead, give yourself a good half day to cover the territory, and bring bear spray. If you’re not comfortable going on your own, Hellroaring Powder Guides (208-360-0385) and Centennial Outfitters (406-276-3463) offer backcountry pack trips, the former to a yurt in the winter and the latter on half-day, full-day or overnight horseback trips to cabins in the summer.

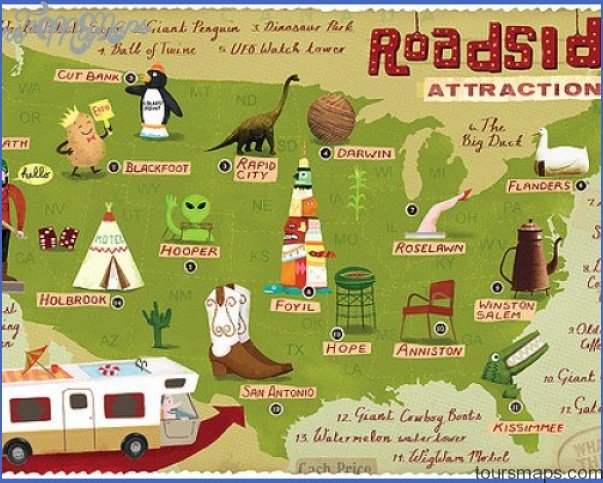

Idaho Map Tourist Attractions Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit

- Coolest Countries in the World to Visit

- Travel to Santorini, Greece

- Map of Barbados – Holiday in Barbados