The Ugly Face of Racism

Mexicans’ relationship with other groups was rocky from the start. During the 1919 strike, Mexican and black workers were introduced under the cover of night into the steel plants to take the place of the white workers. Thus was born the stereotype of these people as scabs. White workers’ prejudice against Mexican and black laborers found in this experience a solid rationale. In the case of Mexicans, it would have to pass a generation before they were more or less accepted by the labor union movement. Racially speaking, Mexicans were wedged between the entrenched white-black extremes. Light-skinned Mexicans were spared some of the most blatant forms of racism, but the dark skin of the majority relegated them to a position closer to blacks than whites in the racial hierarchy. They felt the practical consequences of discrimination in the form of housing segregation and segregation in public places, such as movie theaters. In Gary, for example, Mexicans congregated in south side neighborhoods or colonias, in part because they sought each other’s company, and in part because it was practically impossible to rent elsewhere. A Mexican migrant reported in the 1920s that on the north side they will not rent to Mexicans.10 The concentration of Mexicans in colonias favored the development of businesses that catered to their needs, such as tailor shops, groceries, barber shops, restaurants, and pool halls.

The difficulty for Mexicans to move up the occupational ladder at the workplace kept them stuck in the most dangerous and back-breaking jobs. White supervisors clearly preferred European laborers, allowing them to occupy skilled and managerial positions as they opened. On the streets and even in their neighborhoods Mexicans were harassed by the police. Encounters with Irish and Polish policemen left Mexicans frequently injured and sometimes dead. They received no sympathy from the judges or political authorities. After all, during these times Indiana was a hub of Ku Klux Klan activity around anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, anti-Jewish and anti-black slogans.

The first phase of Mexican presence in Indiana came to a close with the Great Depression. The economic crisis that started in 1929 led to widespread unemployment and poverty. Even the U.S. Steel Corporation, one of the major employers of Mexicans, was operating at 10 percent of its capacity during 1932 and seldom at much more than 50 percent during the rest of the Depression. Mexicans were in a vulnerable position because few Mexicans at the time were U.S. citizens, and they lacked organization and political power. With a high unemployment rate and thousands seeking public relief during the 1930s, whites, blacks, employers, and politicians saw Mexicans as an undesirable competition for jobs, their children as a drain of public school funds, and the needy as an undeserving burden on government and private charity.

Faced with tough circumstances and a hostile environment, unemployed Mexicans and their families thought they would be better in Mexico, especially when the Mexican government invited them back; others were cajoled by local authorities into accepting to return to their country. Whether by train or car, many left during the early 1930s; some paid their own way, whereas local governments and private donations footed the transport bill of the rest. Although the 1930 census had counted 9,007 Mexicans in Lake County, the repatriation campaign drastically reduced that number; Gary and East Chicago alone got rid of 3,600 Mexican residents during 1932. Eventually, Indiana, Michigan, and Illinois contributed 10.5 percent of the 500,000 Mexicans repatriated between 1929 and 1937.11

Indiana’s economy recovered with World War II, attracting again Mexican and Mexican American workers to the state. Their numbers were added to those who had stayed and weathered the depression years. By the 1940s there was already a growing second generation of Mexican Americans born in Indiana; they were now true Hoosiers, as the natives of Indiana are called. Schools, sports leagues, U.S. music, and the media had helped Americanize the children of those who had migrated early in the century. An increasing number of high school graduates were moving up the occupational ladder, and many were serving their country in the armed forces. Since most of those of Mexican descent were still blue-collar workers, they contributed a large share of the industrial labor force.

Others worked in the farms as part of the Bracero program, a United States-Mexico agreement to supply temporary agricultural workers that lasted from 1942 to 1964. With the employment opportunities created by the war and the support for unionization from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Mexican American workers moved into good-paying industrial jobs protected by strong unions. Eventually, a few Mexican American workers figured prominently in the leadership of the unions too. A report from 1967 says that Mexican-Americans appear to have made some progress in achieving status in the East Chicago unions, or in at least those locals that have a large Mexican-American membership.12

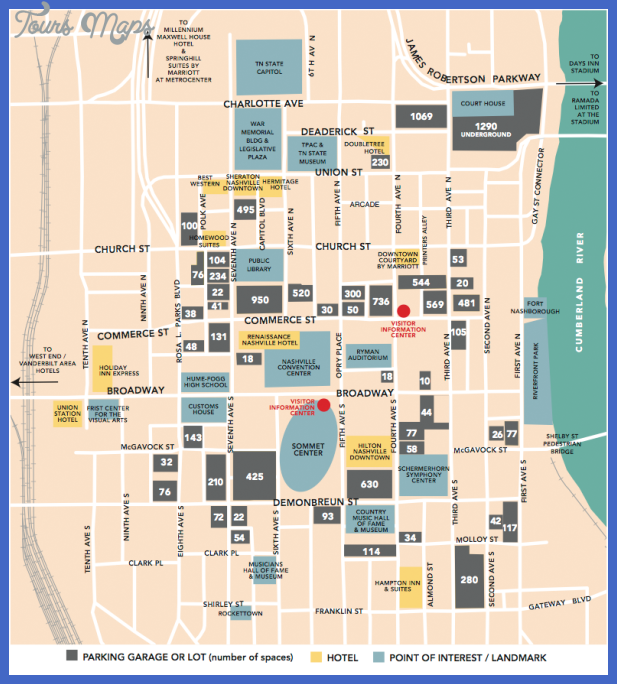

Indiana Map Tourist Attractions Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Pulau Sebang Malaysia with this Detailed Map

- Explore Southgate, Michigan with this detailed map

- Explore Les Accates, France with this Detailed Map

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map

- Explore Gumdag, Turkmenistan with this detailed map