Mississippi Isolated Migrations in the 1970s-1980s

Mechanical cotton pickers notwithstanding, there was still much low-wage labor to be performed in Mississippi this time, in more industrialized sectors,

such as poultry processing. As the civil rights movement expanded beyond the notion of equal rights to include the struggle for economic advancement, mere inclusion in Mississippi’s poultry labor force was no longer enough for blacks. As black labor unionism strengthened in the poultry plants during the 1970s, some owners attempted to import Mexican labor into the industry. For example, in 1977 the B.C. Rogers Poultry plant in Morton began to recruit Mexican Americans from El Paso. Company officials targeted agricultural migrant workers during the offseason. Though a few of these Mexican American workers remained in Mississippi, most did not, and the poultry industry quickly reverted to its status quo of a predominantly African American labor force.

Isolated groups of Latinos in other regions and industries also dotted Mississippi during these decades. For example, government subcontractors charged with seasonal tree planting in Homochitto National Forest employed Mexican migrant workers, many of them undocumented. These workers lived in tents in the forests where they worked, cooking game on kerosene stoves and remaining entirely hidden from public view. Their situation was emblematic of the period’s small Latino migrant population: isolated, invisible, and soon to emigrate from Mississippi entirely.

Latino Boom: The 1990s

If attempts to recruit Mexicans as a permanent labor force largely failed in the 1970s, in the 1990s they were successful, as their scope expanded to all Latino groups. Whereas some Latinos came to work in traditional agricultural jobs, such as the sweet potato harvest in Vardaman or the Delta’s cotton gins, more came for the service and construction industries, particularly casinos in Tunica and along the coast. The greatest number, however, came to work in industrialized agriculture: catfish, lumber, and, most importantly, poultry processing. In 2000 the U.S. census counted 39,569 Latinos in Mississippi, nearly three times as many as were residing there in 1990.

Initially, native-born Mississippians assumed the Latino presence would be temporary, as it had been in previous decades. I think most people thought that this was a temporary thing, said the Chamber of Commerce director in Forest, that they came and were going to go away that this was not going to happen to our community.6 As Mississippians adjusted themselves to the new reality of Latino migration, the state’s relative inexperience with this population led to misconceptions about immigration law, violations of immigrants’ rights, and ad hoc policy making toward the newcomers. On the other hand, many public agencies and businesses actively sought to build their Spanish-language capacity and reach out to Latinos.

Because churches were the only institutions interacting with Latinos for most of the 1990s, officials and employers who would violate immigrants’ rights typically faced no legal opposition. Immigration raids during the 1990s often occurred based on dubious causes, such as a raid in Pelahatchie prompted by complaints from locals that migrants had caused a shortage of rental housing. In an echo of earlier Southern practices of discrimination, in 2002 the Scott County Circuit Clerk began requiring proof of legal presence for those seeking marriage licenses. Though the state’s attorney general affirmed that the law made no such requirement, the county clerk continued to deny marriage licenses to undocumented migrants. Some migrants went to other counties for marriage licenses, and local churches agreed to wed couples who had been denied a license on grounds of immigration status. Shortly after Hurricane Katrina, Latino leaders in affected areas alleged that some stores flatly refused to sell gasoline and supplies to Latinos, stating clearly, We are not serving Mexicans.7

In another incident, the Peco Foods poultry processing plant in Canton fired 200 migrant workers after receiving no-match letters from Social Security despite the fact that the letters specifically stated that workers should not be fired without a thorough investigation into why their social security numbers did not match federal records. Though many of the fired workers paid union dues, they claimed union officials did little to aid their cause; indeed, the union lacked sufficient Spanish-speaking organizers and experience with the immigration issues of the newly arrived Latino workforce. When the company finally agreed to reinstate the fired workers months later, most of the affected workers had either moved away or disappeared into the shadows.

If the seemingly sudden arrival of so many Latinos spawned creative ways to exclude migrants, so too did it encourage creative ways to include them. Churches both Catholic and Protestant became the first local institutions to reach out to Latinos in Mississippi. Indeed, many came to serve as all-purpose help for migrants, with bilingual church employees ministering not only to migrants’ spiritual needs but also to their practical ones. In 2004, Mississippi’s Southern Baptist Convention elected its first Latino officer, Joel Medina, pastor of several Spanish-language churches in Carthage.

Given the lack of a bilingual second-generation to serve newly arrived migrants, white and African American businesspeople and law enforcement officials began enrolling in Spanish classes to better communicate with Latino migrants. Describing her students, one Spanish teacher commented, They’re by and large people who feel that Spanish is here and it’s now.8. As of 2003, 20 of the state’s 152 school districts had hired a translator or designated a bilingual school employee specifically to aid the Latino migrant population. Of course, Latinos generated their own communication media not reliant on translators, and by 2001 Memphis’s emerging Spanish-language press, as well as Mississippi’s La Noticia, was providing news to Latino Mississippians in Spanish.

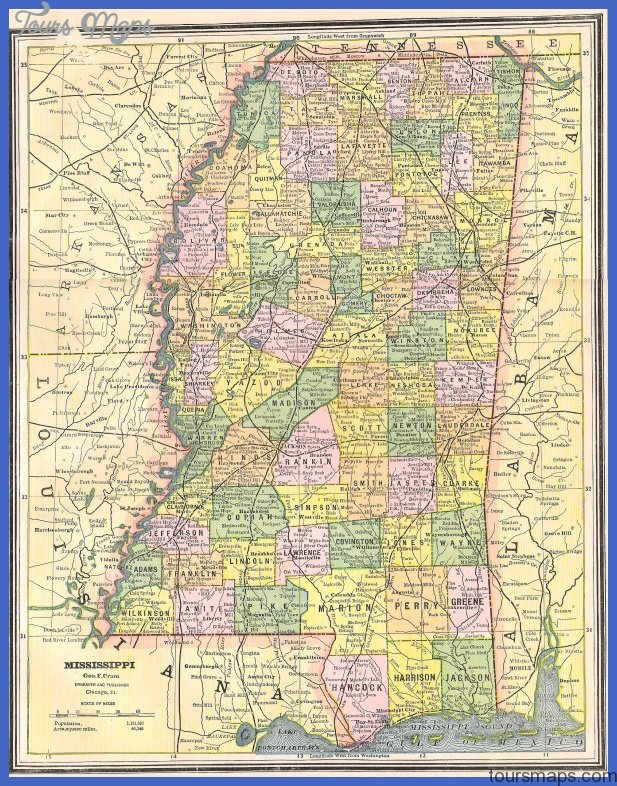

Mississippi Map Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Southgate, Michigan with this detailed map

- Explore Les Accates, France with this Detailed Map

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map

- Explore Gumdag, Turkmenistan with this detailed map

- Explore Telfes im Stubai, Austria with this detailed map