North Dakota historical overview

The history of Latinos in North Dakota starts in 1492 with the arrival of Christopher Columbus (c. 1451-1506) to the Americas. As a result of his discoveries, present-day North Dakota became part of the Spanish Empire, a claim confirmed by further explorations of the Great Plains by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado (1510-1554) in 1542, Don Juan de Onate (1552-1626) from 1598 to 1608, Antonio Valverde y Coslo (unknown-1728) in 1719, and Pedro de Villasur (unknown-1720) in 1720, all of whom claimed the region for the Spanish Crown.

Rather than militarizing and permanently settling the region, the Spaniards contented themselves with establishing a trade presence among the Native Americans. Without a military presence, however, the Spaniards were in no position to defend their interests. As a result, their claims to the region were soon challenged by the French. In 1682 the French explorer Rene Robert Cavalier, Seigneur de La Salle (1643-1687), traveled down the Mississippi River to its mouth. He claimed all the land drained by the Mississippi, as well as its tributaries, for France.

The French hold on the Louisiana Territory was not long lasting. As a result of the French and Indian Wars, French possessions west of the Mississippi were ceded

to Spain under the 1763 Treaty of Paris. Hence, from 1763 to 1800 the Spanish governor-general at New Orleans was officially the ruler of the mid-American prairie regions. With the exception of the Red River watershed, all of present-day central and western North Dakota belonged to the Spanish Crown.

Though it was part and parcel of the Spanish Empire, the north and the interior of the Louisiana Territory was sparsely settled by French Canadian hunters and trappers. Native American nomads made up most of the residents on the Great Plains, where Spanish military control was only confined to the south. Although the Spanish army never reached the Dakotas, having stopped in Nebraska in 1720, the Spaniards maintained a series of forts and frontier posts inherited by the French that extended along the Mississippi as far north as Michigan.

Spanish authorities in New Orleans and St. Louis engaged in fur trading activities on the lower Missouri as early as 1764. In 1785 the new governor of Louisiana, Esteban Rodriguez Miro (1744-1795), took inventory of his domain in a report to his superiors. Beginning in 1789, a few hunters including Juan Munier and Joseph Garreau, known also as Garan were the first Spaniards to explore the Missouri. That very year Juan Munier met the Ponca Indians and was given exclusive trading rights with them by the Spanish. In 1790 Spaniard Jacques d’figlise traveled up the Missouri. As a result of his travels, Santiago de la Iglesia, as he was known in Spanish, confirmed that the French had been actively trading in the region for some 50 years. He also noted that the Mandan Indians had Mexican saddles and bridles, indicating that Spanish goods, if not Spanish traders, had been reaching the region. Alerted of the seriousness of British incursions into their territory, the Spaniards started to assert their rights over the Missouri. As a result, Spanish merchants formed the Company of Explorers of the Upper Missouri and, within the next few years, Spanish expeditions made their way upriver.

In April 1795 John Thomas Evans (1770-1799), a Spanish citizen from Wales known as Juan Evans, led an expedition from St. Louis to the upper Missouri. On September 23, 1796, Evans’s party reached the Mandan villages, located along the Missouri in present-day Oliver County, north of Bismarck, in central North Dakota. He raised the Spanish flag over the villages, distributed a proclamation insisting on the rights of Spain over the land, and ordered British subjects to cease their trading activity. Though it is unknown how many Spaniards visited the upper Missouri after Evans return in 1797, trade continued in the region, and some Spaniards certainly remained behind with the Mandans.

In 1800, through the Treaty of San Ildefonso, Spain secretly transferred the Louisiana Territory to the French, and in 1803 the United States purchased it from Napoleon. As a result of the Louisiana Purchase, North Dakota now belonged to the United States. In May 1804, while Meriwether Lewis and William Clark made their famous travels up the Missouri, they came across Regis Loisel

and Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, a Spanish citizen who was dispatched to explore and trade in the Dakotas in 1803. The two traders were unaware that Spain had given South Dakota back to the French in 1800 and that it was now U.S. territory.

The transfer of North Dakota from Spain to France and from France to the United States did not mean the end of the Latino presence in North Dakota. Manuel Lisa, a Spanish American born in New Orleans who spoke Spanish and a little French, left St. Louis in the spring of 1807 with 45 trappers to trade in the Dakotas. During his trip he carried his favorite book, Don Quijote, which he read constantly. Though most of his group was French Canadian, he also employed a number of Anglo Americans as well as some Latinos. Benito Vasquez, of Spanish background and second-in-command of the expedition, accompanied him on the first journey. Pedro Antonio, called a Spaniard in early accounts, accompanied Lisa when he went upriver in 1812, traveling all the way up the Missouri to the mouth of the Yellowstone. Manuel Lisa was the first trader to penetrate the far reaches of the Missouri valley. A master of dealing with the Native Americans, he was known as Chief Red Head among them. He organized the Santee Sioux and the Yanktonais to harass the English, and he persuaded 40 chiefs of the Missouri River tribes to make peace treaties with the United States.

As a result of Manuel Lisa’s expeditions, U.S. companies became the dominant force in the fur trade. In turn, he became known as the King of the Missouri. A proud Latino and patriotic U.S. citizen, he was also a prominent figure in the war of 1812 against England. He was accused of taking advantage of both the Indians and the government, forcing him to resign his commission in 1817. He staunchly defended his innocence to General Clark in a letter written entirely in Spanish.

Gradually, as French Canadians and Latinos trappers became scarce, U.S. citizens came to dominate the fur trade in the region. Though a minority, the Latino presence persisted in North Dakota. The statistics from the late 1800s, the early 1900s, and the mid-1900s demonstrate that there have always been Latinos in North Dakota. For example, a man known as Old Manuel was employed by the American Fur Company at Fort Clark for several years in the 1820s. A Spaniard known only as Isidoro was killed by a fellow trader at Fort Union in 1841. In the 1840s and 1850s, Jose Ramusio, who was known by the Anglicized name of Joseph Ramsay, was one of the principal hunters at Fort Union. Isidore Sandoval, a Spanish hunter and trapper, served as interpreter for the American Fur Company in several locations along the Upper Missouri. After 1831, steamboats bringing men and merchandise traveled the Missouri with certain regularity. In the 1860s a well-known pilot and captain bore the name of John Gonsollis, a corruption of the name Gonzalez.

In 1861 the Dakota Territory was recognized by the U.S. government. Initially, this included present-day North and South Dakota, and parts of Montana and

Wyoming. In 1862 the U.S. Congress passed the Homestead Act, according to which heads of families or single men or women over the age of 21 could claim half a section of land for a $2 filing fee. So long as they lived on the land, built an 8 x 10-foot house, dug a well, broke the soil, and grew a crop, they could own the property in 5 years. On November 2, 1889, the Dakota Territory was incorporated into the United States as the modern states of North and South Dakota.

By the late 1800s cowboy culture, Latino in origin, had reached North Dakota. During that time, up to one-third of trail riders in the Texas cattle industry were either black or Mexican. In the last two decades of the 1800s several Mexicans were in the state as cowhands, cooks, or general laborers. Personal property records from 1873 Pembina County list a certain John Beck, a likely Anglicization of Juan Becquer, as a Mexican with a property value of zero.

By the 1870s railroad construction was in full swing in North Dakota, attracting workers from diverse backgrounds. Though only a small part of the workforce, Latino men worked on the construction of the Northern Pacific railroad. Eventually, some of these Latinos of Spanish and Mexican origin moved from seasonal to year-round section crews. It took a whole century before Latinos became section foremen in their own rights.

Although it was a rare occurrence, Spaniards, Mexicans, and Mexican Americans came to North Dakota to homestead.1 In 1890 there were 14 Spaniards and 6 Mexicans in the state. In the 1920s there were three farmers in the state listed as born in Mexico. The 1930 census lists 608 North Dakotans of Mexican origin. In that year Grand Forks had 202 Mexicans, Pembina County 172, Walsh County 92, and Cass 35, all working in the beet industry. Ward County had 75 Mexican Americans who were either railroad workers or farm laborers. In fact, from the 1890s to the 1950s, masses of mostly Mexican men, typically accompanied by their families, would make it to North Dakota each fall to work in the sugar beet fields near Williston-Sidney in the west, and the Red River valley in the east. The East Grand Forks sugar plant drew approximately

2,000 migrant workers, half on each side of the Red River, during its first years of operation. By 1954 there were 6,861 migrant workers in the Red River valley, some of them settling permanently. Many of these workers were recruited through the Bracero program, a binational agreement between the United States and Mexico, which lasted from 1942 to 1964 and which brought more than 3 million Mexicans to labor in agricultural fields in the United States. Lee G. William, the U.S. Department of Labor officer in charge of the program, described it as a system of legalized slavery.

In response to the influx of Spanish speakers to the state, community welfare boards, churches, and private agencies came forward to assist migrant workers.2 In the 1930s local Catholic bishops initiated programs to assist migrant workers both socially and religiously. St. Anne’s Church, near Auburn, had been an active

migrant center since 1949. By the 1950s Catholic priests were holding Sunday services in Spanish, sometimes in outdoor masses, in many towns, including Minto, Drayton, Cavalier, Thompson, Reynolds, Hillsboro, Casselton, and Morton. By 1975 there were 7 Spanish-speaking priests, 10 nuns, as well as numerous lay people actively serving migrant communities in eastern North Dakota. By 1993 the number of migrant workers and their dependents in the field of agriculture in North Dakota had reached 30,613. Of these, 14,920 worked in the preharvest of sugar beets; 9,752 harvesting potatoes; 4,579 harvesting dry beans; and 1,040 harvesting soybeans. There were also 132 migrants in greenhouses, nurseries, and food processing. These numbers seem to have gone down since the 1990s. According to a 2000 report from the National Agricultural Statistics Service, the largest decline in the number of hired farmworkers occurred in the northern plains of Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota.

In 1970 there were 2,954 Latinos in North Dakota; in 1980 there were 3,815; and in 1990 there were 5,006. In 2000 there were 7,786 Latinos in the state, and by 2005 the population had reached 10,179. Most Latinos in North Dakota live in Fargo and Grand Forks, where they represent 1.3 and 1.9 percent of the population, respectively. Typically the largest minority in many cities and states throughout the United States, Latinos in Fargo and Grand Forks are a small minority. Since most of them had lived in other states prior to reaching North Dakota, they usually arrive with sufficient language skills. At present, the largest groups of newcomers to Fargo and Grand Forks are Bosnians, Somalis, Sudanese, and Liberians. The second-largest group of Latinos in North Dakota is found in the military, including the Minot and Grand Forks Air Force bases. As of 2006 the number of Mexicans in North Dakota had grown sufficiently to warrant the visit of a mobile Mexican consulate, which was temporarily based at the Centro Cultural de Fargo-Moorhead.

Historically, North Dakota has been the least popular destination for Latinos leaving the Southwest, with only 1 in 50 migrants choosing the state. From 1985 to 1990, 365 Latino migrants, a mere 0.7 percent of Latino migrants from the Midwest, relocated to North Dakota, whereas 474 Latino North Dakotans, 1 percent of Midwest out-migrants, moved out of the state, leaving it with a net migration of -109 people. This general trend, namely the net loss of Latinos through relocation out of North Dakota, seems to have changed. In fact, during the 1990s the west north central states, stretching from Minnesota and North Dakota to Missouri and Kansas, saw their Latino workforce grow by 520 percent.

According to the 2000 census, there were 502,306 workers in North Dakota, of which 4,836 were Latinos, representing 1 percent of the total workforce. There were 384 Latinos and 129 Latinas in the armed forces in North Dakota. Latinos composed 6.5 percent of the men in the state’s armed forces, and Latinas represented 11.1 percent of women. Latino workers are found mostly in Fargo and Grand Forks; however, they are present in virtually every county

in the state, working in almost every sector of the economy. As of 2006 there were approximately 30 Latino law enforcement officers in the state of North Dakota.

In 2005-2006, there were 10 Latino educational personnel in the state of North Dakota, including 1 elementary principal, 3 elementary teachers, 1 English teacher, 4 foreign language teachers, 1 math teacher, an increase from 8 during 2004-2005, 5 in 2002-2003, and 3 in 2001-2002. At present, 0.6 percent of faculty members at North Dakotan doctorate-granting universities are Mexican American/Chicano, and 0.3 percent Puerto Ricans. Nationally, there are only 0.8 percent of the professoriate are Mexican American, 0.3 percent Puerto Ricans, and 1.7 percent other Latinos. As for the four year colleges, there are no Mexican American or Puerto Rican faculty members in North Dakota, and a mere 0.68 percent of other Latinos.

In 2005-2006 there were 100,513 students enrolled in North Dakotan elementary and secondary schools, of which 2,381 were Latinos. In the same period there were 489 Latino students enrolled in North Dakota universities, and 68 Latinos were awarded postsecondary degrees.

Latinos have been helping North Dakota by countering the state’s serious demographic decline, this being the single greatest contribution by that group to the state. Despite growth rates of 1,435 percent in 1880, 417 percent in 1890, 67 percent in 1900, 81 percent in 1910, 12 percent in 1920, and 5 percent in 1930, the state’s population has declined in almost every following decade. From a historic high of 680,845, the population of North Dakota decreased by 6 percent in 1940, 3 percent in 1950, and 2 percent in 1970 and 1990. By 2030 the population of North Dakota is set to drop to 606,566. With 90 percent of North Dakotan counties suffering from massive out-migration, some federal politicians, including North Dakota senator Byron Dorgan, have proposed the New Homestead Act of

2005 to encourage people to settle in rural areas being depopulated. With a growth of -1.95 percent in its total population from 2000 to 2005, North Dakota’s white population simply cannot even maintain a survival rate. During this same period of time, however, the Latino population had a growth rate of 37.78 percent, perhaps putting the future of the state in their hands.

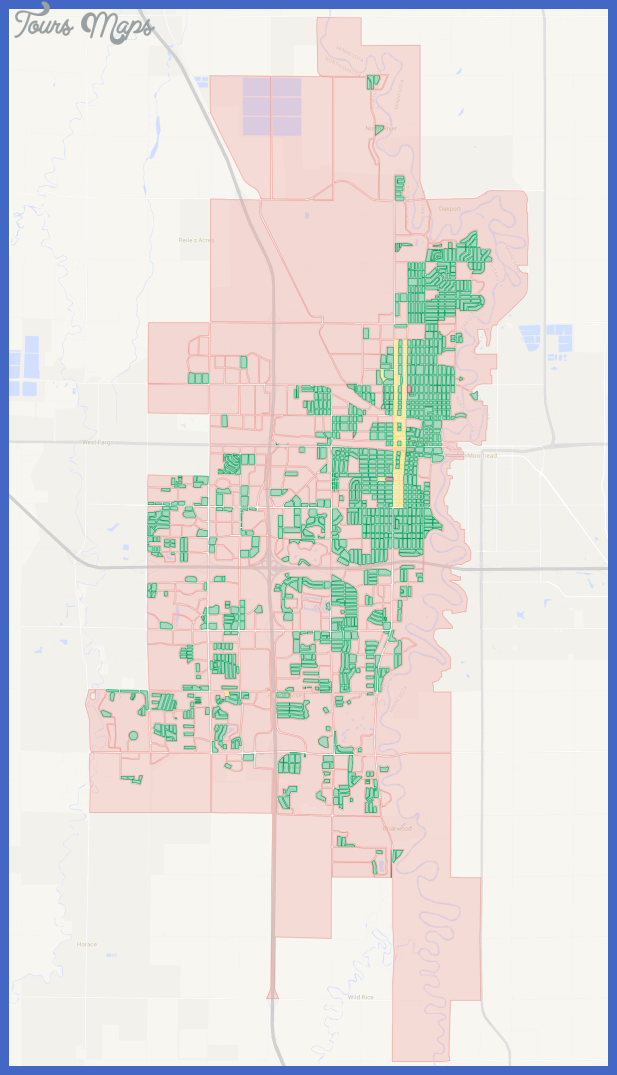

North Dakota Metro Map Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Les Accates, France with this Detailed Map

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map

- Explore Gumdag, Turkmenistan with this detailed map

- Explore Telfes im Stubai, Austria with this detailed map

- Explore Langenselbold, Germany with this detailed map