Thankfully, Taputu, who helped me guide Swell into the haul-out cradle, has taken to me in a fatherly way. In my deepest moments of frustration I go to him. Mostly using sign language, he figures out how to help. Some mornings he even tosses a chocolate croissant up into my cockpit. As the midday heat burns, the noise stops for one short hour while the workers gather to eat in the shade of a dry-docked boat. Taputu insists I join them daily. I sit with my French-English dictionary, noteblog and pen, picking words out of their conversations and vegetables out of my beef curry. The secretary isn’t thrilled about my presence, but day after day I turn her poison into medicine, giving her only kindness. Clock strikes 1 pm, she pulls one last heavy drag on her cigarette, flicks the butt, and everyone gets back to work.

The Ever-Expanding Project List

Life with fewer boys around is simpler, but not easier. To avoid the twenty-minute bike ride to the store, I get by on black coffee and plain oatmeal, lunches from the food truck with the yard crew, and chopped cabbage salads for dinner mixed with whatever canned food I dig out of my stocks. I can deal with the boring food, but the mosquitoes are relentless, and materials and yard fees are quickly adding up.

I finally start grinding the paint off the skeg with the power tools, and end up with toxic bottom paint in my ears, mouth, and eyes, so I copy the yard workers’ look, and wrap an old T-shirt around my face. My arms tire quickly, though, and my strokes come out swirling and random. Every now and then Taputu walks by, grabs the grinder, and passes over the skeg in flawless, methodical strokes to show me how I should do it. I take mental notes, but I’m not strong enough to do it quite like he does. My muscles burn while dragonflies inspect morning puddles.

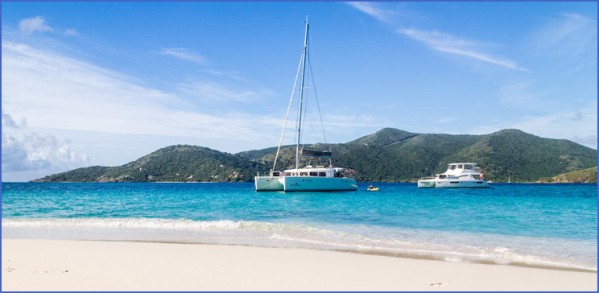

Our Sailing Destinations Photo Gallery

Once I strip the skeg down to bare wood, the small gap between it and the hull is more visible, so the next step is to fiberglass over the skeg-to-hull joint to create a watertight seal. The only fiberglass repair I’ve done is on my surfboards; this is a whole new level. So I set the project aside to gather more information, and tackle a job that seems less complicated: removing the paint around the waterline.

There must be sixteen layers of old paint on the boat and it happens that the very deepest one is bubbling and cracking so it’s back to the unwieldy grinder, which constantly wants to jump out of my hands. If I don’t stay focused, it eats quickly past the paint and into the hull itself.

After a couple weeks, I finish what feels like a heroic paint-stripping performance, but Sylvain, the local fiberglass specialist, gives me some bad news. Because I have made deformities in the hull with the grinder, I’ll have to sand the whole area again to flatten out the worst of them, fill the deepest nicks with two-part epoxy spackle, and sand it level with the hull when it dries.

“And zen, you muss poot seex coats of epoxy resin to make eet wa-tair-proof,” Sylvain says. “And you weell haff to sand lightly between eech one.”

Over lunch one day, Taputu asks me when I’m going to glass over the skeg. I shrug my shoulders. Cesar, a guy who paints boats on the other side of the yard, has joined our lunch circle today and after some discussion, he volunteers to help.

“It’ll only take a couple hours,” he says. “Then maybe you can help me with a big paint job on a boat I’ve got coming up soon.”

I learn volumes about large-scale glassing from Cesar, and the skeg gets glassed to the hull perfectly, but the work list just keeps getting longer. I discover the fiberglass at the back edge of the keel is cracked and rotting, there are several deep blisters in the hull, and the rudder is waterlogged. Sometimes after lunch, I squeeze in a few questions to the yard crew, and if I’m lucky, someone comes over to have a look.

Thierry, the mechanic, lays a hand on my prop one day while looking at the cracks in the back of the keel. The prop shaft wiggles. “Too much loose,” he says, “you need a new bearing.” Sigh.

To deal with this means pulling out the propeller shaft, which looks simple enough, but the bolts on the shaft are corroded. I douse them in penetrating oil for a few days, and then spend hours banging with a hammer to loosen them. Once I finally get the shaft out, Thierry and Taputu help me extract the cutlass bearing from the hull. But it turns out there are no replacement cutlass bearings in the right size on the island, so I have to order one and wait.

One day after lunch Sylvain pokes at a small depression in the hull that appears wet. “You muss be see what’s underneath, looks not good ”

I grind it down to find an old thru-hull that had been shoddily sealed from the inside with caulking.

“I can’t take it anymore!” I cry to the passing clouds as another grinding and glassing job goes on the list. I lie in the grimy cockpit; tears flow down my cheeks. “I’ve had enough of this yard and all the projects and the toxins and being dirty all the time and the gross food and bugs. And the kisses. I hate those disgusting morning kisses!”

I’ve tried to embrace the customary French greeting kissing a person on both cheeks but I’ve decided that there are times and places where this custom is not appropriate, boatyards being high on the list. By 8 am everyone is sweating, but each new day calls for more kisses. There is no way to avoid crossing paths with the many workers and boat owners in the yard each morning. The awkward two seconds of facial proximity feel like an intrusion into my personal space with the bonus souvenir of commingled sweat and saliva. And everyone thinks it’s totally normal!

I’ve learned who to tolerate and who to avoid, slinking around the yard to evade the lonely, unshaven French singlehanders who clearly take advantage of the custom, but often they pop out of nowhere and come at me, with their chapped and saliva-coated lips perked before they even say bonjour.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit