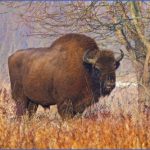

A little under a century ago, it would not have been possible to find any bison in this huge forest; they had all been shot. European Bison had been driven to extinction in the wild. Historically, their range extended over most of lowland Europe from the French Massif Central as far east as western and southern Russia, maybe further east still. But that range decreased as human populations expanded, felling forests as they went and farming larger and larger areas of land, confining bison to what forests remained and to more remote regions of Eastern Europe.

By the 8th century they were largely gone from France, the Low Countries and the western part of today’s Germany except for some isolated populations in less inhabited regions such as the Vosges in the east of France where they lasted maybe until the 15th century. In the 11th century they became extinct in Sweden and the last European Bison in what is now Romania died in 1790. In Poland, however, bison in the Bialowieza Forest were the property of the Polish kings, at least until 1795 when Poland was unceremoniously wiped off the map by its neighbouring countries.

Wildlife Travel To Bialowieza Photo Gallery

‘By the 14th century, Bialowieza had been set aside as a royal forest [rather like England’s New Forest; see Chapter 4] and by the 16th century 300 royal wardens were employed to keep it free of intruders, to prevent illegal logging and to stop any animal poaching by the locals,’ Professor Tomasz Wesolowski of Wroclaw University told me. He has been studying the place for 30 years.

Draconian measures were introduced to protect it. In 1538, King Sigismund II Augustus (1548-1569) instituted the death penalty for poaching a European Bison here. And in the early 19th century when the forest was part of Russia, its tzars also retained old Polish laws protecting them.

So why did bison decline? Habitat degradation and fragmentation caused by agricultural development together with forest logging and illegal hunting were the probable reasons for a steady decline in bison numbers through the 19th century. A burgeoning deer population probably didn’t help either; there’s a finite amount of ground vegetation and shrubs to graze even in a forest as large as this. Only the Bialowieza population – numbering maybe 700 – and one population in the Caucasus (today part of the Russian Federation) survived into the 20th century but the 1917 Russian Revolution and World War I finished them off, albeit indirectly. Occupying German troops killed 600 bison in the Bialowieza Forest for sport and for their meat, hides and horns while, at the end of the war, retreating German soldiers shot all but nine animals. The last wild European Bison in Poland was killed in 1919 and the last one living wild anywhere in Europe was killed by poachers in 1927 in the western Caucasus.

By then fewer than 50 remained in zoos and private collections. Only seven of these were guaranteed pure-bred animals of the type found in Bialowieza, and they formed the founders of a captive breeding programme. By 1929, bison were again in the Bialowieza forest, albeit in a small, confined reserve where they were kept for breeding; ten years later there were sixteen of them and releases into the forest began. Despite losses in World War II, by the early 1970s successful breeding and more releases had brought the population here up to 200. By 2013, 500 bison were roaming the Polish part of the great forest at Bialowieza with another 450 in the Belarus half of the forest. ‘Europe-wide today there are approximately 4,663 bison, about 40% of them in zoos and other breeding centres, the rest wild though some are within large confined areas of land,’ Katarzyna Daleszczyk, a bison expert at the Bialowieza National Park tells me when I interview her for my blog, Back from the Brink (Whittles, 2015). They all originate from the Bialowieza herd.

But Bialowieza is a divided forest. Since the early 1980s, the border between the two countries within it (a length of more than 50 km) has been fenced, making mixing of the two bison populations impossible, a situation that will only change if there is substantial political revision at some future time. On both sides of the border, sections of the forest are designated as national parks. And while much larger areas are subject to commercial forestry, which is highly controversial and the subject of a great deal of criticism from conservationists, forestry interests claim that it is managed sympathetically with wildlife a priority. There is no evidence that any forestry practices here are causing bison a problem.

Having talked to Kararzyna and other bison experts working in this part of Poland to get information about their behaviour and ecology, we thought we might ourselves try finding some bison at dusk when a few come out of the forest to graze in hay meadows and other clearings. So one evening we drove west a few kilometres to Teremiski village, really just a small hamlet surrounded by hay meadows and pasture cut out of the forest a very long time ago; one of several hamlets in the area burnt down by the Nazis in World War II. They cleared people out of the whole area, shooting any members of Jewish families who had lived here for generations. The villages were re-built after the war.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

- Anniston Map

- Wildlife Travel Guide

- Wildlife Travel To Alonissos

- National Wildlife Travel