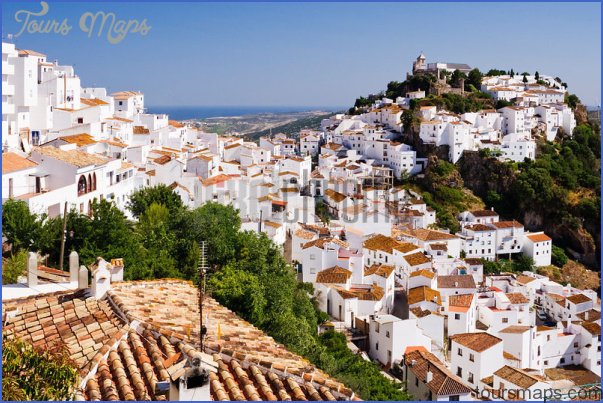

I can watch an expertly executed waltz and admire its elegance. And I can appreciate the more lively dramatic style of a pasodoble, modelled apparently on the sound, drama and movement of the Spanish and Portuguese bullfight. But the only style of dance – more accurately a dance and dramatic music combination – that I find utterly mesmerising is flamenco, a popular form of Spanish folk music and dance from Andalusia in southern Spain. It includes cante (singing), toque (guitar playing), baile (dance) and palmas (handclaps) all blended together in a unique and tantalising combination. I’ve watched performances in places ranging from plush theatres in Seville to backyard bars in Ronda and I never tire of it.

First mentioned in literature in 1774, flamenco is thought to have grown out of Andalusian and Romani music and dance styles and it’s usually associated with the Gitanos – the Romani people of Spain – and a number of famous flamenco artists with this ethnicity. There are more styles than I can describe . and certainly more than I have experienced. In recent years flamenco has become popular all over the world and is taught in many countries; in Japan there are more flamenco academies than there are in Spain. In 2010 UNESCO declared flamenco one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Wildlife Travel To Spain Photo Gallery

So what do I find so entrancing about it? I suppose it’s the drama, the sensuality of the dancing, the rustle of the castanets, the deep-down, earthy wailing of song, the energy, the volcanic yet controlled crescendos, the strumming of the guitar accompaniment and the formality and striking beauty of the costumes. In A Rose for Winter (Hogarth Press, 1955), Laurie Lee, the English poet and novelist who adored Spain, wrote a description of a flamenco session he had watched in Algeciras in the very south of the country. It is the best, most impassioned description I have read. This is what he wrote:

First comes the guitarist, a neutral, dark-suited figure, carrying his instrument in one hand and a kitchen chair in another . He strikes a few chords in the darkness, speculatively, warming his hands and his imagination together. Presently the music becomes more confident and free, the crisp strokes of the rhythms more challenging. At that moment the singer walks into the light, stands with closed eyes, and begins to moan in the back of his throat as though testing the muscles of his voice. The audience goes deathly quiet for what is coming has never been heard before and will never be heard again. Suddenly the singer takes a gasp of breath, throws back his head and hits a high, barbaric note, a naked wail of sand and desert, serpentine, prehensile. Shuddering then, with contorted and screwed-up face, he moves into the first verse of his song. It is a lament of passion, an animal cry, thrown out, as it were, over burning rocks, a call half-lost in air, but imperative and terrible.

At last, the awful solitude of his cry is answered by a dry shiver of castanets, the rustle of an awakened cicada, stirred by the man’s hot voice. Gradually the pulse grows more staccato, stronger, louder, nearer. Then slow as a creeping fire, her huge eyes smoking, her red dress trailing like flames behind her, the girl appears from the wings. Her white arms are raised like snakes above her, her head is thrown back, her breasts and belly taut, while from her snapping, flickering fingers the black mouths of the castanets hiss and rattle, a tropic tongue, eloquent and savage. The man remains motionless, his arms outstretched, throwing forth loops of song around her and drawing her close towards him. And slowly, on drumming feet, she advances, tossing her head and uttering little cries. Once caught within his orbit she begins to circle him, weaving and writhing, stamping and turning; her castanets chatter, tremble, whisper; her limbs are entangled in his song, coiled in it, reflecting each parched and tortured phrase by the voluptuous postures of her body. And so they act out together long tales of love; singing, dancing, joined but never touching.

And if you find Lee’s sensual and dramatic prose somewhat exhausting in itself, imagine the energy expended by the flamenco dancer and her guitarist in the oven-warmth and heavy, aromatic herb-aroma of an Andalusian summer evening. Researching the origins of this culturally important piece of southern Spanish heritage doesn’t get you very far; its origins are pretty much unknown. An array of reasons are usually given to try and explain why that should be, and these include the following: flamenco originated in the ‘lower levels’ of Andalusian society, which lacked the prestige of art forms developed by ‘higher classes’; times were turbulent for the people involved in flamenco culture – the Moors, the Gitanos and the Jews were all persecuted, and the Moors and Jews were expelled by the Spanish Inquisition in 1492; the Gitanos have been fundamental in maintaining flamenco but they have an oral culture while the non-gypsy Andalusian poorer classes were mostly illiterate; and there was a lack of interest in the past from historians and musicologists.

But what about its original inspiration? What was it that inspired flamenco? Did the natural world provide some, maybe all, of that inspiration? Most of the Gitanos, the Moors and the others would have spent their days labouring out in the fields, on the great Spanish plains. Could at least a small part of its origins arise from one of the most unusual and extravagant courtship displays of any bird in the world? And one that can be seen up to a couple of kilometres away. Workers toiling away in the fields would have been very familiar with it; maybe even awe-struck by its extravagance. It’s that of the Great Bustard.

Spain and Portugal hold the largest global population of this magnificent ground bird. I’ve watched them in many parts of both countries on several occasions and they never fail to impress me. Arguably the heaviest flying bird in the world, the male is the size of a large goose, the female smaller. They are shy and inhabit a very open habitat, making it almost impossible to get close to them. Both sexes have black-flecked, rich chestnut brown backs, grey heads and white bellies. As they strut slowly across the ground they pick at the vegetation, take seeds, large insects, maybe a rodent or two and much else that they can find. They are such large birds inhabiting very open, flat or slightly undulating landscapes that it’s even possible to mistake them at a distance for a small flock of sheep. Until a few years ago, I had not managed to see the incredible display that a male Great Bustard puts on to woo nearby females. Either our Iberian visit was a little too late that year … or a little early. On one visit, though, we must have hit it at its displaying peak.

I met up with a good friend, Gabriel Sierra, at a bar in Madrigal de las Atlas Torres, a village about 50 km from Salamanca in central Spain. Its sole claim to fame is that Isabella I of Castille was born here in 1451. A formidable monarch, she brought unity and stability to Spain, substantially reducing crime; but with her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon she also exiled the Moors and Jews that had settled in the country too.

Gabi and I had met some years before when I was researching Great Bustards for a feature in The Independent on Sunday. He had been extremely helpful. The good news this particular morning was that he had just been out to see a large flock of Great Bustards not far away … and some males were displaying. We were off!

Driving along dusty, sandy tracks we stopped well out of sight of where he knew the birds were and where we had a rare opportunity: a small plantation of conifers -planted years ago as a windbreak in this open landscape – between us and them. It was a rare opportunity to get relatively close to them so that we could watch the display I had yet to see but had heard and read so much about.

Most of the land around Madrigal is flat and uninspiring; its grasslands were long ago ploughed up to grow wheat and barley plus a little lucerne as an animal fodder crop. The bustards, birds that would have inhabited the original grassy plains around here, have taken to the replacement crop-growing habitat because the local farmers use very little pesticide and not much fertilizer. Crop yields are low but the cereal varieties they use are more sustainable and appropriate for the very dry summer conditions. Their way of farming allows insects to survive. Birds follow. It is the antithesis of the intensive wheat and barley growing we have in Britain and much of the rest of Europe in which any weeds and pests are killed off with pesticides and the crop is lavished with fertiliser to bulk up its yield; about as far removed from being wildlife sympathetic as a tarmac-surfaced carpark.

We walked quietly a couple of hundred yards into the conifers, then moved behind one tree after another until we were near the far side of the plantation. And the birds were still there; about 100 m away stood 50 or so bustards, mostly females but with a scatter of the larger males. It was the closest I have ever been (it still is) and it was a magnificent viewpoint. We kept very quiet, communicating with hand signals rather than whispers.

Almost immediately, Gabi started pointing to the left. A male was beginning his display. He was puffing out his throat pouches, inflating them with air until his neck had blown up to the size of a small football, his head disappearing ‘into’ it. He fanned his chestnut tail and inverted it over his back. He did the same with his wings, inverting them to form huge white rosettes of feathers from under his body that bulged out on either side and completely covered his back in a flurry of pure white. He appeared to have turned himself inside out just as some of the descriptions of this amazing transition claim.

It was incredible. This rich chestnut-brown bird had metamorphosed into a shimmering white mass. And he now proceeded to show off while most of the female bustards around got on with their feeding! Rhythmically shaking his now white plumage, he seemed to billow like a ship in full sail as he strutted a couple of paces in one direction, then another.

In less than a minute it was all over. His tail and wings returned to their normal positions, his neck deflated and suddenly I was looking at a large brown bird once more. And he returned to feeding, nonchalantly picking here and there on the ground as if dissatisfied with the whole transformational act. The experience was surreal; it was as if some magician had performed a trick so convincing in front of my very eyes that I couldn’t be sure whether this rather plain bird had transformed itself into a Persil-white foaming bundle or not. The speed with which this incredible transition is accomplished is such that, from a distance, many observers describe what they see as something akin to a bush covered in white spring blossom that’s present one minute, then disappears.

But why have such an extravagant display at all? Why not just do a few bows, flutter their wings a little, sing some fabulous song or raise a few feathers on their head to attract a mate just like many other birds do? A good voice is not much use on the large, open and frequently windswept plains they live on. The sound of the wind would drown it out and no other bustard would hear it. The only way to attract a mate is to be seen … and bustards (there are 26 different species worldwide and all of them have amazing displays) have become masters of the catwalk, modelling some of the most eye-catching bird fashions in the world. Don’t bother with a bit of crest-raising or tail flicking; what female bustard is going to notice that out here on these vast, flat expanses. Instead, the message seems to be: if you’ve got it, then flaunt it; bustard displays are designed to be seen!

Gabi, helpful as ever, pointed out more males – some close, others distant – that displayed just as thoroughly as the first. We watched them for an hour or more. It was spellbinding; I had had a ringside seat to an awe-inspiring ritual. Later that day, from tracks and small roads, we could see other, much more distant Great Bustard males performing their magic; some were maybe a couple of kilometres away. The white shimmering, caught in the afternoon sunlight, appeared for a few seconds, sometimes perhaps nearer a minute, then disappeared as if it was a mirage, not really there at all.

So what would the Gitanos, the Romani people of Andalusia – many of them working long hours in the countryside – have made of this visual display of nuptial spring extravagance? They must have noticed it every year on the spring-chilled plains of southern Spain where these birds were almost certainly more abundant in the past. How could they not? And they would have been very familiar with these birds for another, very different reason – food. Well before the days of bird protection, country people would have trapped or shot the occasional bustard. A bird of this proportion would feed a family for days and the meat, by all accounts, was very tasty indeed.

It was one of the reasons why they declined – to eventual extinction – in England through the 17th and 18th centuries. Until then they were not uncommon, especially in southern England. Hunting and habitat change, especially the increasingly intensive use of farmland, has caused their decline across much of Europe but Spain and Portugal still have large populations. In the UK, the English enclosures divided up the large tracts of open land they favour with hedges and other structures, effectively destroying their habitat. The last pair of Great Bustards bred in England in 1832 though in the last decade or so a population has been reintroduced to the Wiltshire downs but is struggling to re-establish itself in any numbers.

With such familiarity with these birds on the Spanish plains, is there not a chance that the Gitanos might have adopted some of its flamboyance, combined it with the brightly coloured, extravagant dresses the women wore traditionally for special occasions, and added in a heady mix of sensuality and passion that’s part of life for these people? Did the strutting male bustard, thrusting his head haughtily one way, then the other, an intense mass of white feathers, trying to attract the attention of his female harem, help inspire the weaving and writhing, the stamping and turning of the tightly clad flamenco dancer, her body in one voluptuous posture after another?

In the flamenco it’s the girl that does the alluring, sensual writhing. How else can it possibly be? For the bustard it’s the male showing off all his manly attributes to any females willing to watch. Flamenco perhaps just reversed those roles. They added in the clicking castanets and the rhythmical hand clapping – reminiscent of the metronome-tempo calls of cicadas in the heady summer warmth maybe – and the crisp, vibrant rhythms of the guitar, their traditional instrument. And then you have it: the elegant, supreme, passionate, voluptuous invocation that’s called flamenco.

Go and imbibe it. You won’t be disappointed. But, when you do, imagine that amazing ‘brown bird to shimmering, spring-blossomed bush transformation’ that takes place every spring across these warm, soporific Iberian plains.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

- Anniston Map

- Wildlife Travel Guide

- Wildlife Travel To Alonissos

- National Wildlife Travel