Everything seemed to go wrong in that week. I ended it up on the night of 2 July by freeing Miranda and leaving the yacht to sail herself through the night. I refused to struggle any longer with one sail change after another. During my half sleep I could hear the yacht turning round in circles, and in the morning the log showed that she had moved only 9 miles during the night. Wearily I struggled out of my blankets after five hours, when I longed for another twelve hours sleep. As I was making some coffee I was thrown across the cabin, which not only caused great pain to the tail of my spine, the first part of my body to hit the other side, but shattered the Thermos flask I was holding, so that it took me ten minutes to sweep up the splinters scattered all over the cabin floor.

At the end of this third week Blondie, who had escaped the storm, had sailed farther in a straight line from Plymouth than I had. However, he had been bearing away to the north, passing within 300 miles of Greenland, and he was still 85 miles farther from New York than I was. Lewis had gained on me too, and was now only 350 miles astern.

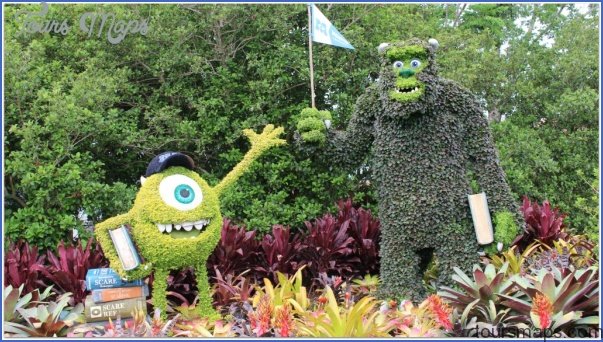

Win A Trip To Atlantic Photo Gallery

During the next week’s sailing I came to terms with life. I found that my sense of humour had returned; things which would have irritated me or maddened and infuriated me ashore made me laugh out loud, and I dealt with them steadily and efficiently. Rain, fog, gale, squalls and turbulent forceful seas under grey skies became merely obstacles. I seemed to have found the true values of life. The meals I cooked myself were feasts, and my noggins of whisky were nectar. A good sleep was as valuable to me as the Koh-i-noor diamond. All my senses seemed to be sharpened; I perceived and enjoyed the changing character of the sea, the colours of the sky, the slightest change in the noises of the sea and wind; even the differences between light and darkness were strong, and a joy. I was enjoying life, and treating it as it should be treated -lightly. Tackling tough jobs gave me a wonderful sense of achievement and pleasure.

For example, on 5 July I was fast asleep, snug among my blankets at 9.30 at night. I woke with a feeling of urgency and apprehension. A gale squall had hit the yacht, and I had to get out quickly on deck to drop sails. This is one of the toughest things about sailing alone – switching from fast sleep in snug warm blankets, to being dunked on the foredeck in the dirty black night a minute later. Conditions have to be at their worst to demand the urgency, and I had that dry feeling in my mouth as I dragged on my wet oilskins in the dim light. Then I was standing in the water in the cockpit, and from there pressing against the gale. I made my way to the mast, and wrestled with the mainsail halyard with one hand, slacking it away as I grabbed handfuls of mainsail with the other hand and hauled the sail down. The sail bound tight against the mast crosstree and shroud under the pressure of the wind, and the slides jammed in their tracks. The stem of the yacht was leaping 10 feet into the air and smacking down to dash solid crests over my back. The thick fog was luminous when the lightning flashed, but I heard no sound at all of thunder; it was drowned by the thunderclaps from the flogging sails. I scarcely noticed the deluge of rain among the solid masses of seawater hitting me.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit