The bow waves rumbled with a hint of distant thunder, and in the cabin I could hear them breaking and rushing along the hull. It was a delightful change after days of plugging into wind.

My next entry in my notebook was twenty-two hours later, and in between so much happened, and I had had such strong sensations, that I could not recall them all.

I had been below for two hours after setting the twin headsails, when I noticed by the telltale compass attached to the cabin table that the course was erratic. Occasionally a sail filled with a loud clap. I found that the clamp which locked Miranda to the tiller was slipping, and I knelt on the counter to begin fixing it. The boat was yawing to one side or the other, and each time one of the sails would crack with a loud report. I turned round and grabbed the tiller. We were going at a great pace, and the following seas would pick up the stern and slew it hard to one side. The yacht would start broaching-to with one headsail aback, promising serious trouble ahead if I did not check it. I could not leave the tiller, and wondered what I should do. It was, however, exhilarating, charging through the seas downwind, and if I took the tiller myself for four hours the 36 miles would be a valuable step towards New York. Fortunately I became so sleepy that I could not keep my eyes open, and realised that I must get the sails down.

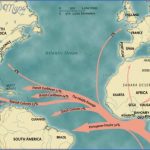

Atlantic Map World Photo Gallery

I thought hard for some time before making up my mind how to tackle the job. At a favourable moment I made a rush for the foredeck, after slacking off one sheet from the cockpit to let the spinnaker pole forward, and to decrease the area of sail offered to the wind. As soon as I stepped on the deck I realised that I was in for big trouble. I found a 6omph wind, which I had not noticed in the shelter of the cockpit with the yacht bowling downwind. My sleepiness had been partly to blame, but the storm was blowing up fast. When I slacked away the halyard, the bellied-out sail flapped madly from side to side. The noise was terrific, and the boat began slewing wildly to port while the great genoa bellied out and flogged at the other sail with ponderous heavy blows. I was scared that the forestays would be carried away. I rushed back to the tiller and put the yacht back on course, and then forward again to grab some of the genoa in my arms and pass a sail tie round it to decrease the area. I had the 380-square foot genoa on one side, and the 250-foot jib on the other. Next, I slacked away the halyard to let the lower half of the genoa drop into the sea, while I struggled with the spinnaker pole on that side. I had more trouble with the jib, because I could not get the sail clew free from the spinnaker pole; the sail was like a crazy giant out of control. In the end I twisted the foot of the sail round and round at the deck, and finally I got control. It was dangerous work, and I was grateful and relieved to find myself whole in limb and unsmashed at the end of it.

I realised that I had a serious storm on my hands. I spent five and a quarter hours on deck without a break, working hard. After lashing down the spinnaker poles, I next started on Miranda, who was already breaking up. The topping lift had parted, letting the spanker drop, and the halyard of the little topsail had gone. I could easily have got into a flap; it was now blowing great guns, and I had to stand on the stern pulpit while I worked with my hands at full stretch above my head at the wet ropes jammed tight. Miranda’s mast was 14 feet high, and free to rotate with the wind. I was standing with stays and wires all round me, and could have been swept off the pulpit horribly easily if the wind had suddenly changed direction. I told myself that it would be much worse if I had iced-up ropes to deal with; not to fuss; and to get on with the job. There seemed fifty jobs to do, but I did them all in time. I lowered the mainsail boom to the deck, and treblelashed it there. It was only after I had finished that I became aware of the appalling uproar, with a high-pitched shriek or scream dominating. I managed to strip off both Miranda’s sails, and secured her boom with sail ties. I reckoned that the wind was now 80mph (I still think of winds above 60mph in terms of miles per hour instead of knots, because of getting used to the speeds of my seaplane propeller slipstream in ‘mph’).

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit