I swung round and headed for the middle of the island. I recalled the warning of the Admiralty Sailing Directions that ships passing within a mile and a half of Lord Howe Island in a north-wester ran the risk of being dismasted by violent squalls of wind. I fastened the safety-belt, a weary effort. The island close up was quite different from my imaginary picture of it: it looked huge with two black trunks of mountains rising straight from the sea into a heavy roll of dark clouds. Above the lines of surf at the base were solidly packed palm-trees, and above them, almost sheer bare rock disappeared in the cloud. Only the lagoon was as I had pictured it, a stretch of bright colours, with patches of startling white sand on the bottom. I started circling to choose the best spot for alighting, but with a whizz, the seaplane was suddenly hurled downwards at the lagoon. Cameras, sextant, protractors, pencils, chart, everything flurried round my head like a whirl of leaves. Only the safety-belt held me in the seat as I clutched frantically at the control-stick and instrument board. The seaplane fetched up with a bump that jarred me back into the seat. I dived straight down to the surface, taking only a glimpse at the water ahead for obstructions.

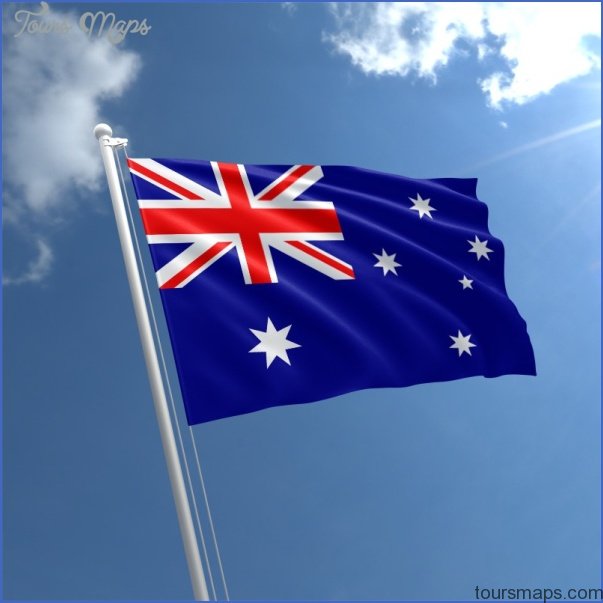

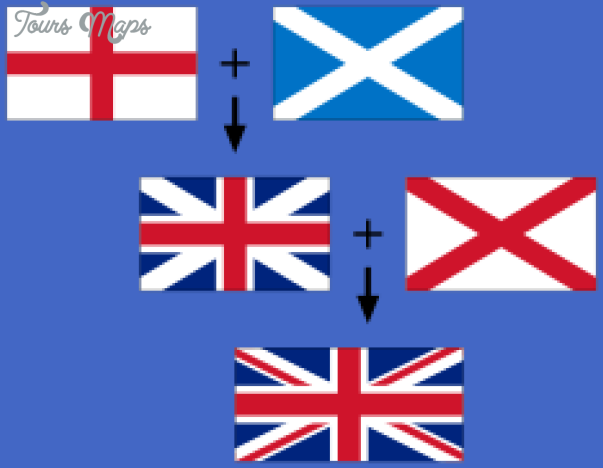

Australia Flag Photo Gallery

The height of the waves showed me that there was depth enough, yet at the last moment I jibbed because I could see the lagoon bottom so clearly that I thought that there was no water there at all. The thought of another bump brought me to my senses in a fraction of a second, and I closed the throttle. The seaplane alighted like a duck, and at once began drifting astern at a great pace. I scrambled out of the cockpit and freed the anchor from the tangle of gear in the front cockpit, heaved it overboard. The line wrenched at my arms and nearly tugged me overboard. I clung to the float strut with one hand with the line scouring through my other hand, until I could get a turn round the mooring ring. The anchor ripped and jerked along the lagoon bottom. The flight of 575 miles had taken me seven hours and forty minutes and I had one hour and forty minutes petrol left.

I was relieved to see a launch coming. A second followed, and they began circling the plane. Men and women aboard stared as if a Dodo had arrived. I kept on bellowing, ‘Where’s the best place to moor?’; they kept on waving handkerchiefs, pointing cameras and shouting things. There was one man I began to concentrate on; his voice was loud enough to be heard above the others; he was thickset and powerful looking, and did not get excited. It was agreed that I should moor in the boat pool, a deeper hole in the shallow lagoon, and I asked him to tow me there. ‘Why not move across under power?’ he asked. I explained that the seaplane would be blown over if I tried to taxi across that wind. He said nothing, but picked up my anchor line, and began towing aslant the wind. I was depressed and fearful of mooring out in this rough weather, but there was nothing else that I could do. I moored with a stout rope to two great anchors, and the launch took me shore. As I arrived at a little wooden jetty, night had fallen. I had got in none too soon, though, curiously, I had never once during the flight been afraid of the risk of being caught by dark. P. J. Dignam, in charge of my petrol, was waiting for me. He asked me what time I left Norfolk Island and a string of other questions. I could not remember when I left Norfolk Island, and later I did not remember snapping at him, ‘Don’t ask so many questions !’ which he declared I did. I had been hard at it since dawn and had seldom worked under greater mental strain. Dignam invited me to stay at his house.

I slept fitfully, waking to blasts of wind furiously flogging the treetops. At about 6 o’clock the most violent squall of all brought me wide awake; I expected the roof of the house to be stripped off. I lay in the dark for a while longer, and then got up to dress feeling as if my bones had been weary for a week. I went to call young Dignam, but found him already awake. I asked him to take me to the seaplane, and we moved off under a heavy grey sky before dawn. At the edge of the trees the stretch of water lay between the steep black hill and us.

‘Isn’t that where we moored the plane?’ I asked him. ‘I don’t see her,’ I said. We walked on. ‘Ah, there she is!’ I said, but not yet certain. A little closer, I added, ‘She looks queer to me.’

‘She looks queer to me too,’ said Dignam.

I could not make out why, but day was breaking fast. ‘Sunk!’ I said, though not yet believing it myself. At last we could see only too clearly; the tail of the seaplane was slanting above the surface, like a big fish diving into the water.

We dragged out a boat and rowed across. The entire seaplane, except the tail and the float ends, was under water.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit