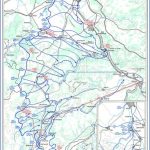

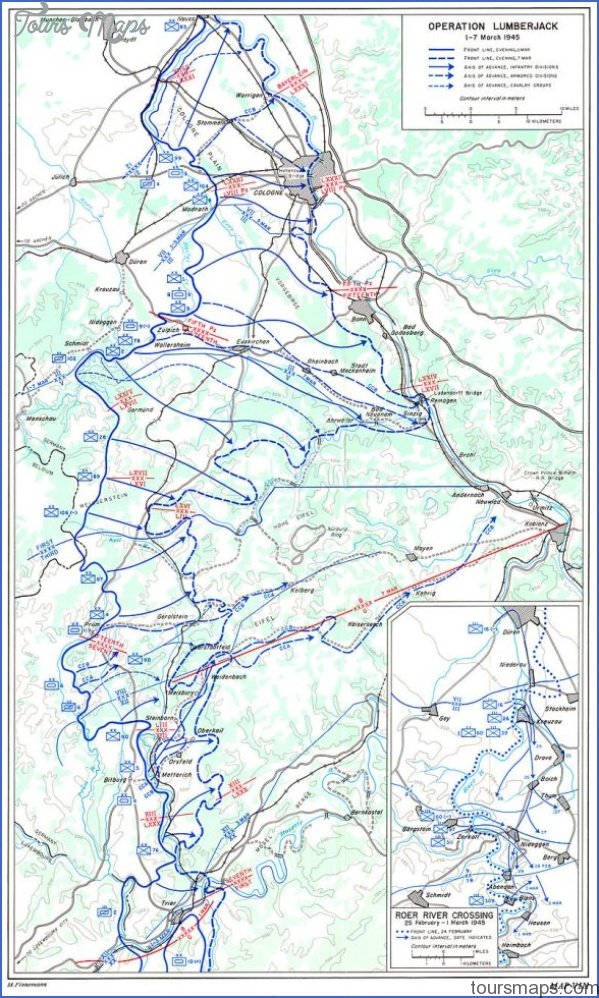

LUDENDORFF BRIDGE MAP

Everyone knew the bridge would be destroyedthe only question was when.

The physical structure of the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen no longer survives, but the bridge lives on as a powerful memory of the cataclysm of World War II. A leitmotif of the last days of that war, it provides insight into fate’s power to alter and, as in this case, hasten the course of history.

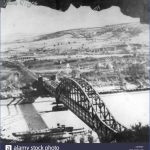

Built by Grun and Bilfinger during World War I, the bridge was one of many constructed across the Rhine to facilitate the transport of German troops and materiel from east to west. One of the chief lobbyists for construction of the Rhine bridges was General Erich Ludendorff, Germany’s wartime commander at the time, after whom the bridge was named.

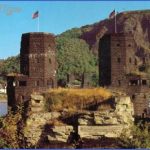

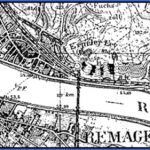

The firm of Grun and Bilfinger designed the double-track railroad bridge as a steel arch with through-truss side spans. At each end were two fortresslike stone towers with openings for guns and interior storage for military supplies and personnel. Trains passed over the bridge and then through a 1,200-foot (366-meter) rail tunnel bored into the Erpeler Ley, a 600-foot (183-meter) basalt cliff opposite Remagen, a town between Koblenz and Bonn. We were across the Rhine, on a permanent bridge; the traditional defensive barrier to the heart of Germany was pierced. The final defeat of the enemy… was suddenly, now, just around the corner.

LUDENDORFF BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

With the outbreak of World War II, the bridge became a strategic military link between Germany and the two fronts, facilitating military transport westward. Coexisting with the bridge’s offensive utility was a defensive plan to demolish the bridge to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. To that end, the bridge was mined with explosives in 1938, a year before the war began. To confirm the infallibility of this contingency plan, the detonator’s ignition system was systematically tested.

That the bridge would be blown up was anticipated by the Allied forces as well. The idea that a Rhine bridge could be seized intact was considered preposterous. Operating from this presumption, Allied troops began massive bombing of the Rhine bridges in September 1944 to disrupt Germany’s communications and trap German troops on the western side of the Rhine.

On March 7, 1945, with Allied forces fast approaching, German commanders gave the order to detonate the bridge. Nothing happened. The impossible had occurred: the ignition system malfunctioned. A reluctant volunteer ran out to the bridge and lit the fuse by hand. Instead of destroying the bridge, however, the partial explosion momentarily lifted it off its foundations and then returned it, albeit tenuously, to its prior position. The U. S. Army’s 9th Armored Division, the first Allied troops on the scene, scrambled across and cut wires leading to other demolition charges. Within a week, four German officers held responsible for the loss of the bridge were court-martialed and executed. Gaping holes in the bridge deck had to be covered so Allied troops and tanks could cross.

The capture of the Ludendorff Bridge significantly hastened the end of the war. Allied forces crossed what had been a formidable barrier and penetrated Germany with unanticipated speed. Within a week, seven U.S. divisions crossed the Rhine and established the first Allied bridgehead in the German heartland. Frightened German citizens, soldiers, and officers huddled in the Erpeler Ley rail tunnel, where the detonation order was given.

Like many of Steinman’s bridges, the Mackinac is distinguished by its color: the towers were painted ivory and the spans and cables green to express, according to Steinman, the opposite forces of tension and compression.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Doncaster, United Kingdom with this detailed map

- Explore Arroyito, Argentina with this Detailed Map

- Explore Belin, Romania with this detailed map

- Explore Almudévar, Spain with this detailed map

- Explore Aguarón, Spain with this detailed map