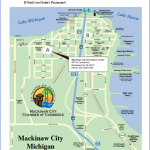

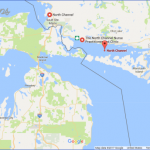

MACKINAC BRIDGE MAP

More than 42,000 miles (67,600 kilometers) of cable wires support the roadway.

The onset of World War II curtailed large-scale bridge construction through the 1940s. Moreover, the 1940 collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge (see here) had a sobering effect on American bridge design, the most visible and immediate change being the incorporation of deep web-truss stiffeners on long spans. David B. Steinman’s research into aerodynamic stability, in particular, would renew public and professional confidence in the viability of large-scale suspension bridges.

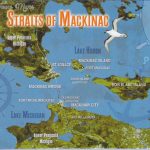

In 1888, from the steps of the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, Cornelius Vanderbilt declared, “What we need is a bridge across the Straits.” He wasn’t the first to want a crossing over the frigid 5-mile (8-kilometer)-wide Straits of Mackinac (pronounced MAKinaw). But it wasn’t until 1951, when reports of salt caverns under the straits proved untrue, steel became available once again after two wars, and three consulting engineersDavid B. Steinman, Othmar Ammann, and Glenn Woodruffwere retained, that plans for the bridge proceeded. The Mackinac Bridge is my crowning achievementthe consummation of a lifetime dedicated to my chosen profession of bridge building.

MACKINAC BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

In the mid-twentieth century, all the major suspension bridges in the United States were built by one of two highly skilled rivals: Ammann or Steinman. Steinman built a great number of bridges, but Ammann was building the world’s longest suspension spans. For Steinman, the Mackinac project presented a long-awaited opportunity (in fact his last) to build a bridge longer than any other. In 1953 he agreed to take the job on speculation; Ammann withdrew. To finance the bridge, $100 million worth of bonds were sold that were not paid off until July 1986.

Ground was broken on Mighty Mac in 1954. Its two steel towers rose 552 feet (168 meters) above the straits on piers that descended 210 feet (64 meters) below water. The bridge was braced with 38-foot (12-meter) trusses; widely spaced, the deck can swing out as much as 35 feet (11 meters) in high winds, but moves very slowly out and back to center. With a critical wind velocity of infinity, it has an aerodynamic stability never before attained in a bridge. Having an anchorage-to-anchorage length of 8,614 feet (2,626 meters) and a total length of nearly 5 miles (8 kilometers), it was the world’s longest overall suspension bridge span for many years.

David Barnard Steinman (1886-1960) grew up in a poor neighborhood under the Brooklyn Bridge, a lifelong inspiration. An assistant to Gustav Lindenthal, he worked on the Hell Gate Bridge in New York (see here). With longtime partner, Holton D. Robinson, he constructed his first major bridge, the Hercilio Luz Bridge in Florianopolis, Brazil (1926), which was followed by the design of more than four hundred bridges, including the Carquinez Bridge in California (1927), Mount Hope Bridge in Rhode Island (1929), St. Johns Bridge in Oregon (1931), Henry Hudson Bridge in New York (1936), and the Mackinac Bridge. Steinman was a scholar, a tireless self-promoter, and a prolific author and poet, whose extensive studies of aerodynamic stability expanded the possibilities of long-span suspension design.

A view of a cable suspended from the towers gives some idea of the bridge’s gargantuan proportions. Its roadway at midspan is approximately 200 feet (61 meters) above water. The Drivers Assistance Program escorts timid motorists, about 1,200 annually, over the bridge.

Like most early cable-stayed bridges, Maracaibo’s cables held zinc-coated strands, which were economical and easy to handle. They have been replaced several times because of the corrosive effects of the humid saline climate.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Doncaster, United Kingdom with this detailed map

- Explore Arroyito, Argentina with this Detailed Map

- Explore Belin, Romania with this detailed map

- Explore Almudévar, Spain with this detailed map

- Explore Aguarón, Spain with this detailed map