MYSTERIOUS CAROLINA BAYS SCATTERED ALL OVER THE MID-ATLANTIC COASTAL PLAIN are mysteries. Some half million of them. Most are located in the Carolinas, hence the name Carolina bays. Bay comes from the types of shrubs usually found growing within them red bay, sweet bay, and loblolly bay. Elliptical in shape and ranging in size from a few acres to several miles across, Carolina bays are shallow depressions surrounded by a slightly raised sandy rim. All are oriented in a northwest-to-southeast direction. Most hold water at some point, though they can be dry for several years in a row; some of them hold water year-round. Phelps Lake (Route 21) and Lake Waccamaw (Route 28) are examples of the latter that we visit in this book.

One interesting thing (out of many) about Carolina bays is that scientists can’t tell us how they got here. Numerous theories have been proposed some logical, some laughable. After viewing the first aerial photographs of bay country, scientists thought they had it figured out. The bays made the land look like the cratered surface of the moon, so they concluded that the bays were the result of an enormous meteor shower. Some even suggested that it was the same event responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs. But meteor impacts are nearly always circular, even those where the meteor strikes obliquely. Plus, no impact evidence has ever been found to support the theory. Perhaps the most convincing evidence against the meteor theory (or a similar one involving a comet explosion) is the age of the bays. Radiocarbon dating of peat deposits shows ages ranging from 30,000 to 5,000 years. That would have been some meteor shower to last for 25,000 years! No wonder the dinosaurs became extinct. Oh, wait a minute, the dinosaurs died out some 65 million years ago!

Other theories presented over the years provide more comic relief than matter for serious study. Of course, the person who suggested that Carolina bays are dinosaur footprints was purposely trying to be funny. (One hopes, anyway.) And whoever implied that aliens had a hand in it had obviously spent too many nights camped out in crop circles. But the prize must go to the person who, in all seriousness, proposed that it was fish who created the Carolina bays. The theory goes that back when the sea covered this part of the land, this was their spawning ground. The fish congregated in huge schools and the motion of their fins caused the water to scoop out the shallow depressions.

Fanciful postulations aside, scientists do have a working theory that does a fairly good job of explaining how the Carolina bays came into existence. The explanation requires at least six years of postgraduate geology study to comprehend fully. The layperson’s explanation goes something like this: When the sea receded, it left behind pools of water. Strong winds churned up the water, causing it to carve out the depressions.

Either that, or all the fish left stranded by the receding water started flailing around in a panic attack, digging out the bays in the process!

Suggs Millpond lies near the northeast end of a group of Carolina bays in Bladen County known as the Bladen Lakes. The most visitor-friendly of the Bladen Lakes, Jones Lake, is next up on our route. Jones Lake is a state park, which means it has the usual amenities, such as picnic grounds, campground, and trails. What makes it popular among the locals, though, is its sandy beach. You can also rent canoes and paddleboats in season. The three-mile Lake Trail encircles the lake, providing wonderfully scenic views and an intimate experience with the shoreline ecosystem. Chances are good you’ll have most of the trail to yourself any time of year. A short side trip from Jones Lake is Turnbull Creek Educational State Forest, which features exhibits interpreting the history of forest use in the Carolina bay region.

From Jones Lake, our route passes very close to another Carolina bay named White Lake. White Lake is somewhat unusual among Carolina bays in that its water is crystal clear, not tea-colored like most. Its white-sand beaches and clear water have attracted visitors for generations. Some early efforts were made to protect all or part of the lake, but none were successful. Today, the entire shoreline is heavily developed. Its worthiness for exploration is only as an educational juxtaposition to the largely pristine lakes surrounding it.

We make our first of three Black River crossings at the tiny community of Clear Run. But before you cross, pull off to the side of the road and walk onto the bridge. The first thing you notice is that the river is appropriately named black as tar when viewed on the surface. Scoop up a glassful and it looks like iced tea. The color comes from natural tannins that have leached into the water from vegetable matter. If the water level is not too high, you can see the remains of the steamer A. J. Johnson on the left bank a few yards downstream. From the mid-1700s into the early twentieth century, the Black River served as an important transportation artery. Cotton, naval stores, lumber, and a few other commodities were floated downstream to the port at Wilmington. Early vessels were canoes and rafts. Shallow-draft steamboats began plying the river in the late 1800s.

A pond cypress reflects on the water at Suggs Millpond during sunrise.

Amos J. Johnson operated his steamer business from his home base here in Clear Run. In its heyday, the town consisted of a shipyard (where the steamer was built), a cotton gin, a turpentine distillery, a sawmill, and several general mercantiles. With the decline of forest resources in the early twentieth century and the advent of the automobile, traffic on the Black River ceased. The A. J. Johnson sank in 1914, and Clear Run became a ghost town. Remarkably, the cotton gin and several buildings still exist and remain largely unchanged. The general store from the 1870s sits by the road, with original merchandise still waiting on its shelves.

We can thank the descendants of Amos Johnson for the preservation of so much of Clear Run’s rich history and for placing the site on the National Register of Historic Places. The McLamb and Norris families have been caring for the land for more than century. While the site is not open to the public, you can see the general store and another mercantile as you drive by. Please respect the rights of the owners by staying in your car.

At our second crossing of the Black River, a large antebellum house with expansive porches overlooks the river. Laura Dern, playing the promiscuous Rose, graced this house with her seductive antics in the 1991 film Rambling Rose. The bridge over the river is shown in the film several times minus the guardrail and covered with dirt to hide the asphalt.

Between the Rambling Rose home and the NC Highway 53/11 bridge downstream, the Black River flows through a wild, hauntingly beautiful section called Three Sisters Swamp. Here the river has no main channel and fans out through the cypress swamp in numerous small braids. The swamp is home to a rich diversity of reptiles and amphibians, mammals, birds, fish, and mussels. Somewhere tucked in the heart of the swamp is a cypress tree sporting a small metal tag bearing the numbers BLK69. If you happen to find this tree while canoeing the Black, pause for a moment and consider that this tree germinated around the time Constantine the Great established Constantinople. Yep, this tree is well over 1,600 years old, officially making it the oldest living thing known in the eastern United States. Dr. David Stahle, the University of Arkansas scientist who dated the tree, believes there are other trees on the Black that were here when Christ walked the earth!

Workers gather crude turpentine from the great longleaf pine forests of eastern North

Carolina in 1903. Library of Congress

Three Sisters Swamp on the Black River takes on a golden hue during a foggy sunrise.

You can see a few old-growth cypress trees from the NC 53/11 bridge, but the only way to experience the river fully is from the water. You can put a canoe or kayak in at most of the road crossings. Just be forewarned that it’s mighty easy to become twisted around in Three Sisters Swamp. People have been known to wander around in it for days before finding their way back out. But then, as writer Lawrence Early says, there are worse fates than getting lost in a cypress swamp.

Our third Black River crossing is on the NC Highway 210 bridge. A few miles farther down, the route ends at Moores Creek National Battlefield. The first battle of the American Revolution to take place in North Carolina occurred here on February 27, 1776. A force of about 1,000 Patriots soundly defeated the 1,600 Loyalists who were attempting to cross Moores Creek. The battle marked the end of permanent British control over the North Carolina colony.

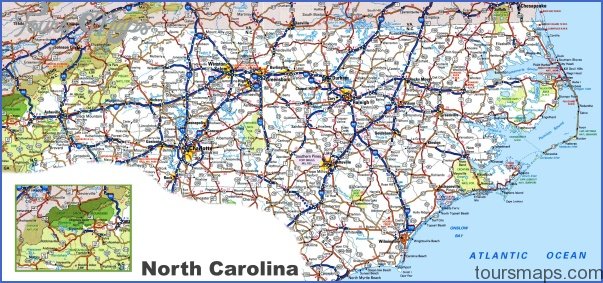

NORTH CAROLINA MAP Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit

- Coolest Countries in the World to Visit

- Travel to Santorini, Greece

- Map of Barbados – Holiday in Barbados