Philadelphia Migration and the Labor Force

Cigar-making factories would continue to be an important source of employment well into the 1950s, but the industrialization of Philadelphia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries created other job opportunities that encouraged

many more Spanish-speaking migrants to move to the city. Mexicans and Puerto Ricans went to Philadelphia as contract laborers for the steel industry, the railroads, and the agricultural industry. Census data from the 1910s and 1920s show an increase in lodging facilities for single women and an increase in women working outside of the home; they often worked as clerks or managed boardinghouses. Many of these changes reflected the conditions prevailing during World War I. Eighty-five percent of the Spanish-speaking residents of Spring Garden (a Spanish-speaking enclave in Philadelphia) in 1920 had arrived in the United States between 1914 and 1919, with 65 percent having arrived between 1917 and 1919.6 These numbers indicate that as men went to war, labor shortages prompted higher rates of migration by Spanish-speaking migrants to Philadelphia, while also creating opportunities for Spanish-speaking women to work outside of the home.

When the Great Depression hit in 1929, all occupational categories suffered tremendous losses, with unskilled blue-collar workers being the hardest hit of all. Despite the grim economic conditions, the city’s Spanish-speaking populations continued to grow. One reason was that the Great Depression devastated Puerto Rico too, and for many on the island, migrating to Philadelphia still looked like a more attractive option. Moreover, agricultural workers continued to be recruited into the region. Eventually, Cubans and Puerto Ricans became the dominant groups among the Spanish-speaking migrants, with Puerto Ricans overtaking Cubans after 1945.7

This period also marked the beginning of significant Latino migration to other areas of Pennsylvania. Bethlehem Steel, located in the western Pennsylvanian town of Bethlehem and one of the largest employers in the state at the time, had always relied on migrants from Eastern Europe to fill its dirtiest and most dangerous jobs. However, after the passage of federal immigration restrictions in 1921 virtually stopped the flow of such migrants, the company found itself suffering from a severe labor shortage. Observing that the immigration restrictions did not apply to Mexicans, the company secured an exemption from the 1885 Contract Labor Ban and in 1923 negotiated a contract with the Mexican consulate for close to one thousand Mexican laborers.

Acclaimed agricultural economist Paul S. Taylor interviewed many of these workers for his research on Mexican migration. The interviews suggest that the workers generally felt they were treated fairly, but that biases against them resulted in their assignment to the hottest and dirtiest work in the coal ovens. Citing the supposed Mexican tolerance for extreme heat, company managers kept Mexicans in the ovens long after European employees would have been promoted.8 Other companies, such as the Pennsylvania Railroad, similarly offset labor shortages through the recruitment of Mexican contract workers.

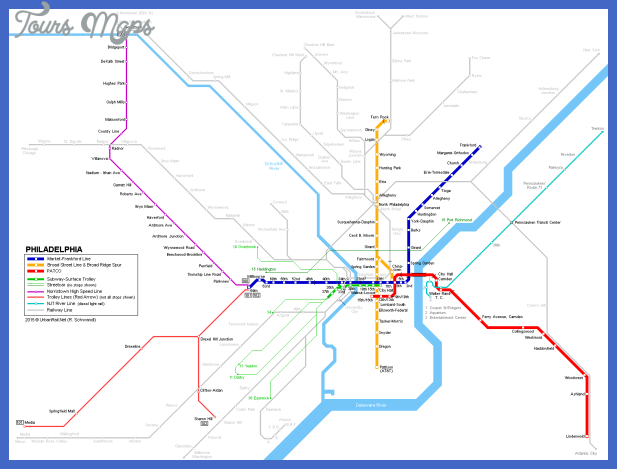

Philadelphia Subway Map Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map

- Explore Gumdag, Turkmenistan with this detailed map

- Explore Telfes im Stubai, Austria with this detailed map

- Explore Langenselbold, Germany with this detailed map

- Explore Krotoszyn, Poland with this detailed map