The early twentieth century is pocketed with Connecticut interaction with the peoples and places of Latin America and the Caribbean. Yale University professor Hiram Bingham directed an expedition to Peru in 1914 and 1915. His partial excavation of the site of Machu Pichu, high in the Andes, resulted in the importation of thousands of artifacts from Peru. The intellectual exchanges as a result of Hiram Bingham’s expeditions resulted in long-term connections between Peru and Connecticut. In 2006, Peruvian officials began discussions with Yale University for the return of artifacts about 90 years after Bingham’s expedition.

One of the earliest cases of Latin American and Caribbean migration to Connecticut involves a soldier by the name of Apolinario Pinkeiro. Pinkeiro was born on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent in 1893 and registered his ethnicity as Portuguese. He migrated to Bridgeport, enlisted in the Army, and was honorably discharged in 1919. His service is recorded as a Buffalo Soldier in the U.S. invasion of Mexico at the Battle of Carrizal, Chihuahua, Mexico. Pinkeiro’s experience illustrates how his multicultural background was translated into one racial category; according to his skin color and the social construction of race in Connecticut, Pinkeiro was considered colored and inscribed into the Buffalo Soldier unit, despite his registration as a Portuguese native of St. Vincent.

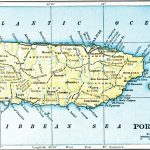

In 1917, the passage of the Jones Act provided U.S. citizenship rights for Puerto Ricans who migrated from the island to the mainland, including Connecticut. This increased the benefits for laborers who decided to make the transition to the mainland and discouraged the maintenance of residence in Puerto Rico, where neither an elected governor nor the right to vote in federal elections existed.

A military service record for Alescander Cornelius from Bridgeport is an example of the service of Caribbean migrants in World War I. He was born in St. Croise, Virgin Islands, and listed himself as colored and Episcopal. Cornelius was married to Nanie Scott from Danville at A.M.E. Zion Church in Bridgeport and worked as a laborer at American Tube and Stamping Co.14 Another military service record lists Horton Dockendorff as born in the United States, but his

father Abel was from Lima, Peru. Dockendorff characterizes himself as white, Congregationalist, and single. He served as a sergeant in World War I in France and worked as a clerk at Winchester Repeating Arms Co. in New Haven both before and after the war.15

When child labor laws forbade the use of children in the tobacco industry, recruitment of African Americans from the South by tobacco agricultural firms supplied the growth of the industry during World War I. During the depression, newly migrated European laborers (youth and adults) also labored in the tobacco fields. Connecticut’s child labor laws had no statutory age limits and therefore, up through 1944, Connecticut’s farmers brought children, up to 1,000 African American boys each summer from the South, to work camps on farms.16 The University of Connecticut’s agricultural experiment stations played key research roles in providing the tobacco industry with enhanced techniques for cultivating shade tobacco and in managing the tobacco agricultural operation.

Relationships between Latin America, the Caribbean, and tobacco growers were evident in the growth of the industry. Although the shade tobacco industry’s best profits were during the 1920s, several large companies operated profitable operations in Connecticut within the Shade Tobacco Growers Association. The growers housed workers in migrant camps along the Connecticut River Valley in northern Connecticut.17 Some of the tobacco was grown and processed in Connecticut, but after World War I tobacco was also shipped to the Dominican Republic, where workers processed the tobacco into smokable commodities that were reimported into the United States for sale. Connections with South America also existed as newly developed Ecuadorian seed cultivars were annually imported to Connecticut.

During World War II, Jamaicans were recruited to work in the tobacco industry in Connecticut and they settled just outside the tobacco farms in Bloomfield. As part of the War Food Administration, Connecticut was one of the largest importers (2,053 workers in 1945) of Jamaican labor to support the tobacco industry. An additional 1,001 Jamaicans were recruited to work in over 24 industrial businesses in Connecticut in 1945.18 Jamaicans risked their lives to come to work in Connecticut during World War II. After many Jamaicans served building and maintaining the Panama Canal under the direction of the United States, they were shipped on war boats through the Gulf of Mexico, while evading German U-boat attacks, and up the Mississippi River.19 In 1957 Kenneth Jones, a member of the House of Representatives in the Jamaican Parliament, made a visit to the mayor of Hartford to lobby for more Jamaican workers in Connecticut. He commented on potential tensions between Jamaicans and Puerto Ricans over work opportunities in the tobacco industry and emphasized that Jamaicans would work harder to retain the privilege of annually returning to the United States.20

Puerto Rico Map Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World