Starting in the late 1680s, Quakers began to migrate to the British North American colonies in large numbers. By the middle of the eighteenth century,

they had become one of the most influential Protestant sects in the New World. Their struggle for religious liberty in Britain and New England, their work

in establishing the colonies of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and their protests against slavery gave them a prominent role in shaping American political

culture and social mores.

The English Civil War and Interregnum (16421660) spurred the creation of new religious sects, having been energized by far-reaching debates over

political and religious authority in Britain. This included such transitory groups as the Seekers, the Ranters, and the Fifth Monarchy Men but also groups

soon to become a permanent part of English Protestantism, namely Baptists and Quakers.

The Quakers grew out of the radical wing of Puritanism, a movement that sought a thorough reform of the Church of England along Calvinist lines.

Puritans, and later Quakers, stressed liturgical simplicity, personal self-discipline, and the work of the Holy Spirit. Quakers departed from the Puritans on

the means by which the Holy Spirit accomplishes this work. Puritans held that the Spirit works principally through Scripture, while Quakers thought the

Spirit could communicate directly. Soon, Quakers came to understand the Spirit as an inner light given to believers to guide them along their spiritual

journey. Without creeds, churches, or paid clergymen, Quakers sought to recreate the primitive Christianity of the New Testament in seventeenth-century

England.

Quakers found early converts among separatist Puritans and Baptists in the English North and West Country, Wales, and the cities of London and Bristol.

Separatist Puritans in Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire, and Derbyshire were among the first to exhibit traits that would come to be associated with

Quakerism in the 1650s, which included spontaneous meetings of believers driven to heights of spiritual ecstasy by the Holy Spirit. These men and

women referred to themselves as friends, thus giving the movement its eventual name, the Religious Society of Friends.

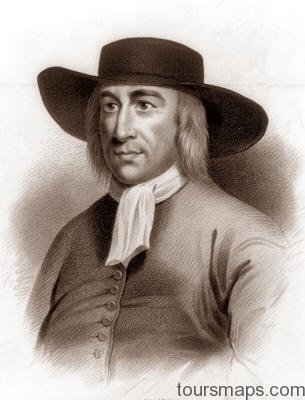

Quakerism was spread through these counties in the English midlands and northwest by such itinerant ministers as George Fox, William Dewsbury, and

James Naylor. In the hands of George Fox, as recorded in his influential Journal, the movement acquired many of its distinctive beliefs and practices. Fox

understood the Christian faith to preclude paying homage to presumed superiors, so Quakers were enjoined to use thee and thou in addressing everyone,

regardless of social position, and to refuse to tip their hats to the rich, the well born, and the powerful. Also, Quakers were to dress and act in a plain

style, lest anyone show the sin of pride through refinement in clothing and demeanor.

These early teachers brought Quakerism into ill repute among Anglicans, since they echoed the social and economic radicalism of civil war groups such

as Levellers and Diggers. Quakers responded to their critics by channeling the movement through a system of weekly, monthly, quarterly, and yearly

meetings and winning strategic converts among the gentry and nobility. Notably, meetings for business involved both men and women, and their

acceptance of the spiritual authority of women became a Quaker distinction. Margaret Fell and William Penn provided examples of affluent, well-born men

and women who could practice Quakerism while nevertheless preserving the fabric of the English social order. In fact, William Penn’s role in organizing

the colonies of West New Jersey and Pennsylvania testified to a new outlook within the movement, one geared toward building institutions and

contributing to the development of the English colonial system.

Quakers Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World