SALGINATOBEL BRIDGE MAP

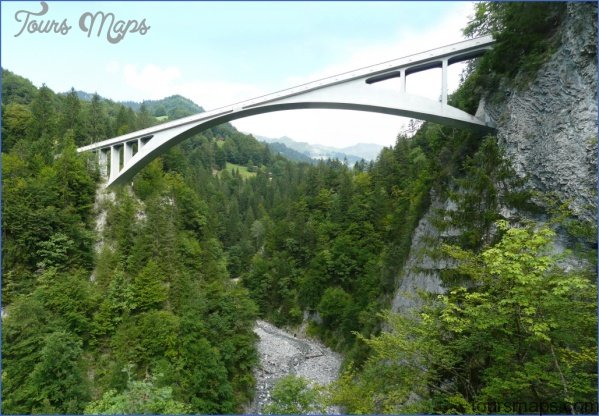

Crossing Salgina Gorge, near Schiers, Switzerland Designer/Engineer Robert Maillart Completed 1930 Span 295 feet (90 meters)

Material Reinforced concrete Type Arch

By eliminating everything but structure itself, beauty can emerge. The Romans’ genius for concrete forms would fade with their empire, not to be revived until the end of the nineteenth century, when concrete, now reinforced with metal, was developed simultaneously in Germany, America, England, and France. Pioneers of this new composite material, initially called ferro-concrete, include Joseph Monier (1823-1906), a Parisian gardener whose reinforced-concrete flower pots would yield the patents from which the large German civil engineering firm of Wayss and Freytag would emerge; the self-taught builder Francois Hennebique (1842-1921), whose tireless exploration of the material from about 1879 led to the first of his many patents in 1892; and Eugene Freyssinet (1879-1962), the inventor of prestressed concrete. Reinforced concrete’s structural and aesthetic possibilities would reach a sublime synthesis in the bridges of Swiss engineer Robert Maillart (1872-1940). Like Telford and Eiffel, Maillart sought deduction rather than addition, economy not ornament, believing that only when everything but structure itself was eliminated could beauty emerge.

The idea that there is an independent art form of engineering structure has its origin in studies of Maillart’s work.

“Reinforced concrete does not grow like wood, it is not rolled like steel and has no joints like masonry,” Maillart wrote in 1938, a succinct clue as to why his work was revolutionary. He understood that reinforced concrete was a unique material, wholly new and expressive, with intrinsic properties that could be exploited structurally and aesthetically. His bridge designs pushed its capacity to resist compressive and tensile stresses. Between 1900 and 1940 Maillart designed forty-seven bridges, all but three still standing, which are acclaimed for their fluid lines and minimalist beauty.

SALGINATOBEL BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

Maillart’s 1901 Zuoz Bridge was the first to be constructed of hollow concrete boxes. Its spandrel walls, however, were solid, like those of traditional masonry arches. When the bridge developed cracks, Maillart began to investigate new forms. In his design for the Tavanasa Bridge (1905), he removed the spandrel walls altogether, exposing the arch as well as its true structural function.

His masterpiece, the Salginatobel Bridge, spans a precipitous Alpine gorge with such graceful inevitability that its silhouette has become an icon of twentieth-century architecture. Like the Tavanasa, the Salginatobel Bridge is a hollow-box, three-hinged arch located in the Graubunden canton. However, as Maillart’s biographer David P. Billington noted, the Tavanasa design is transformed at Salginatobel: the stark white bridge appears to emerge from one side and leap across the ravine, liberated to breathtaking effect by the elimination of the heavy stone elementsabutments, arcading, and facaderendered structurally unnecessary by the use of reinforced concrete.

For the Tavanasa Bridge over the Rhine at Tavanasa, Switzerland, Maillart experimented with an open-spandrel form that anticipated the one at Salgina. An avalanche destroyed the Tavanasa span in 1927.

During the decade between the Salginatobel’s completion and his death, Maillart would build his most important works. They included the curving Schwandbach Bridge (1933) at Schwarzenburg, in which he explored a limited number of fundamental forms with ever-greater technical and aesthetic virtuosity. In his lifetime, his radical, imaginative designs were beyond most. Historian Sigfried Giedion, whose influential Space, Time and Architecture of 1941 brought Maillart’s work to a larger public, described his career as “a continuous fight against economic pressure and public dullness.” Maillart died in 1940 without the recognition his work enjoys today. In 1947 the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted an exhibition of his work, the first museum show ever devoted to the work of one engineer. A close-up of Salginatobel’s dynamic underside reveals the increased width of the arch and cross wall. The bridge’s monumental towers were to be clad in granite. However, given the Depression-era economy and the favorable opinion of the exposed lattice steelwork, the Port Authority decided to leave the 604-foot (184-meter) towers unsheathed.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Anshun China with this detailed map

- Explore Coahuixtla, Mexico with this detailed map

- Explore Deloraine, Canada with this detailed map

- Explore Daund, India with this Detailed Map

- Bakel, Netherlands A Visual Tour of the Town