Barely half an hour passes before strengthening winds yank me from my prone position to reduce sail again. I try to rest through the day, but the worsening conditions keep me busy. By evening the seas have doubled; we’re in an all-out gale. There’s no way to maintain our course as the wind has swung farther south. I try three reefs in the main plus the storm jib, hoping to point higher into the wind, but Swell’s collisions with the steep seas feel awfully violent. Thankfully, Monita maintains the steering, but I still don’t get any sleep again that night bracing, heaving, and wincing. Waves swat us here and there; Swell shudders and flexes. By 4 am it’s too much. I crawl out on deck in the deafening winds and douse the main entirely, but without the drive a bit of mainsail provides, we’re blown father and farther west. Each mile lost to leeward will have to be sailed double, to windward, later.

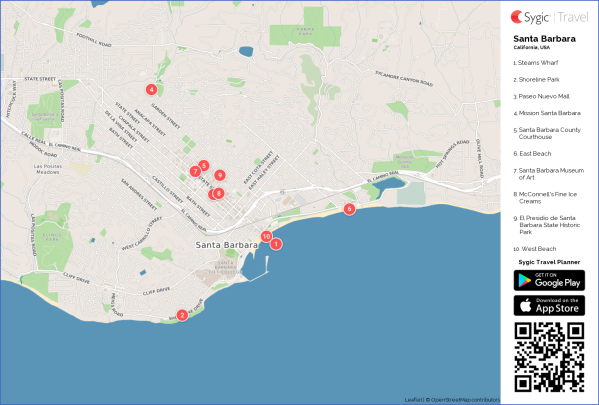

Heave-to, I think, as the storm tactic comes to mind. I remember my Santa Barbara rigger, Marty, walking me through the procedure. Turn the wheel to windward, making the bow come across the wind as if you ’re going to tack, but instead of releasing the sheet, backwind the jib and leave it where it is. Then turn the wheel hard back over to leeward. The back-winded jib pushes the bow one way, as the rudder steers the other. I give it a try. To my disbelief, our hectic advance turns into a calm and steady lifting and falling over the chaotic seas. Swell’s western drift decreases enormously. I collapse into my berth at dawn and manage to sleep for a few precious hours.

“Swell, Swell Elise here. You there, Lizzy?” I crawl out of my bunk at noon when I hear Chris’s faint call over the radio.

“I’m here,” I muster.

“I made it to Samoa this morning!” he says.

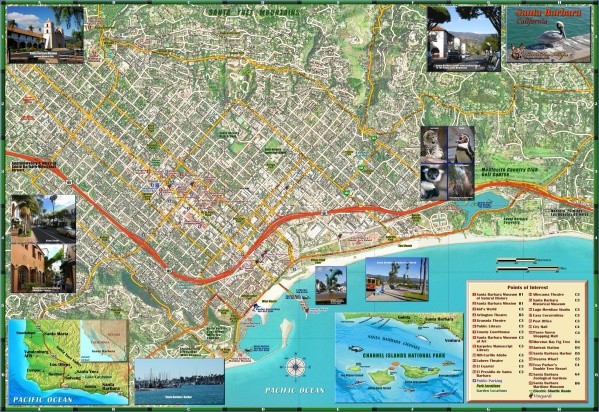

Santa Barbara Map Photo Gallery

“Great, Chris so glad you made it safely.” My words come out slow and fragmented. It feels like my brain and my tongue have become disconnected from nearly three days without sleep. Bit by bit I explain my situation. I tell him that my radio modem got wet, so I can’t receive weather info or emails. He takes down my position and says he’ll look at the weather forecast and call back in a couple of hours.

Later, he reports back: “Okay, Liz, you’re in the middle of a huge, nasty front. But sometime tonight the wind should turn east and decrease slightly. When it does, you will have about eighteen hours to get as far southeast as you can. After that, it will shift back to the southeast and get very strong again. You’ll have to go hard during that window of time if you want to make French Polynesia.”

My heart sinks. I feel like giving up.

“You can do this, okay? I’m going to talk you through it,” he encourages. After signing off, I clean up the explosion in the cabin and heat some soup, eating for the first time in thirty hours. After surveying the still-raging gale outside, I lie back down and try for a bit more rest, praising the heave-to storm tactic that has allowed for this miraculous “time-out.” I sleep hard for a couple more hours, then awaken suddenly, scrambling up on deck to check the wind direction.

Sure enough, it has calmed a bit and already shifted slightly to the east. I rush to reset the sails and get back on course. The big, sloppy leftover seas slow our progress, but we’re able to hold almost a direct course for the westernmost islands in French Polynesia through the night. Chris feeds me weather information and confidence twice the next day. On the following morning, June 8, 2008, I relay him my position.

“You’re almost there, Liz! Keep going! It looks like Bora Bora is going to be your best bet for landfall. If you make it, I’m going to put you up in a hotel when you get there,” he says. The thought of this much-too-generous offer helps me escape from the hellish world I am currently trapped in.

“Really?” I ask.

“Really.”

I drive Swell hard through that day with the remaining east winds, but the gale has blown me over sixty miles west. Chris is clear that I must try to make landfall by the following day; the gale to follow looks fierce.

“I hate you, ocean. I hate you, lightning. I hate being wet. I hate sailing!” I scream.

I don’t shut my eyes once that night. Adrenaline has completely taken over. My body aches, the sores on my rear from the constant wetness have chafed open, and my hands are worn raw from the constant sail adjustments, but in spite of the pain, I tend religiously to Swell’s trim to keep our speed up and our bearing as direct as possible. Don’t give up the ship, I hear Barry’s voice in my mind. If I can stay focused, landfall might be possible by dark the following day.

The next morning I’m fairly optimistic, with thirty-nine and a half miles left to go at daybreak. I tack between a few squalls, and gain a fair bit of headway by 8 am. A small island appears from behind a squall not far to my east, but the guideblogs proclaim its south-facing pass is “dangerous and not to be attempted in heavy seas.” Bora Bora is next now just thirty-seven miles away. I must make it before dark!

I try different sail layouts to see what will allow me to sail closest to the wind, since it’s blowing hard directly from my destination. The storm jib and triple-reefed main are not enough: I’m making less than three knots, at about thirty-five degrees off the wind. I try the headsail reefed down with similar results. I tack back and forth all morning, sometimes feeling like I’m going backwards. I turn on the engine and add the force of the motor but gain less than a knot and a few measly degrees. My spirits drop.

“Come on, are you serious? Throw me a friggin’ bone!” I call to the sea. But there will be no bones, no breaks, no special exceptions. It’s going to be a jaw-clenched scrap for those last thirty-some miles.

Two hours later a teeny speck of the island appears on the horizon ahead. Something in me grows fierce. I will do anything not to spend another night on this godforsaken ocean. Chris has already bloged my hotel room, and the image of dry sheets, a hot shower, and fresh food provides intense motivation. I roll out the entire headsail and crank it as flat as my strength will allow. With a slight shift of the wind in our favor, our course is now just ten to fifteen degrees off the island! Swell is overpowered, but it’s the only way I can make significant headway. The starboard rail is fully buried in the churning blue waters, but we plow upwind at over six knots.

The strongest gusts drive us on our side, then we round up a bit, and slam ferociously.

The rig shudders so violently that I feel its vibration throughout my body. I grit my teeth at the helm and push on, praying nothing breaks. I notice the aluminum sleeve of the furler is bowing and flexing more than usual, though. The thru-hull on the galley sink is stuck open too, so on port tacks, water gushes up through its drain and cascades across the floor. The bilge pump runs to keep up with its constant flow.

By 2:30 pm I have fifteen miles to go. More than once I give up and reef the headsail in, but then my stubbornness takes over and I roll it back out. I’m too close not to make it. I drive Swell like a senseless madwoman steering by hand, thighs tensed and braced, standing at the helm for hours and hours, indifferent to the blasts of sea, wind, and sun. I haven’t eaten since the soup. The door to the forward cabin is jammed shut due to the wet, swollen wood, so I haven’t been able to get a change of clothes. They are probably all wet anyway. All I can think is get there, get there, GET THERE!

The island’s size increases painfully slowly. I do my best to ignore the swaying rig. About seven miles off, the seas finally begin to decrease. But it’s after 6 pm; there is no way I’ll make it into the lagoon before dark. My little chartplotter doesn’t have enough detail to get me safely through the pass. I speak with Chris at 6:30 pm, forlorn and defeated.

“I didn’t make it,” I report. “I tried my hardest, but I just couldn’t make it. I’m seven miles off and the wind is still howling on the nose.”

“I know that pass well,” he replies. “I’ll give you the waypoints to get you in. It’s wide and deep and there aren’t too many obstacles once you’re through it.”

I cringe at the thought of a dicey entry in the dark, but I plug the points into my little GPS anyway. Around 9 pm, I hover near the pass, trying to decide what to do. Go in and risk hitting the reef in the dark? Or stay out and spend another miserable night on the sea? The silhouette of the island’s towering crater mountain looms above. Beckoning lights shimmer around its base. But my vision blurs with fatigue and I decide I am safer staying outside for one more night.

While straightening up the cockpit, I hear some cruisers chatting on the VHF radio and decide to interrupt.

“Hello. This is the sailing vessel Swell. I’m approaching the Bora Bora pass and want to come through in the dark. Can anyone give me suggestions on the easiest place to anchor for the night once I’m inside?” A man’s voice comes back.

“Is this Liz on Swell?”

“Yes, it is,” I reply, taken aback.

“This is Steve on Ironie. We met in Panama, remember?”

“Hi, Steve! Do you know if the lights on the channel markers are working? I’ve been at sea fifteen days, the last few very rough, I’m exhausted and just need to get my anchor down somewhere safe tonight.”

“Okay. Yes, all the lights are functioning. When you pass the final green marker, turn to about eighty degrees and you will see a big fishing boat all lit up. Head toward that boat for about a mile. It’s deep water. The anchorage is just before it to the east. There is an open mooring available next to us. Call when you get closer and we’ll flash a spotlight to guide you in,” he says.

“Thank you! I will see you soon, so long as I stay off the reef.”

A squall rips over me a mile from the pass. I impatiently wait for it to clear, and then drop the remaining sails and motor for the green and red lights marking the entrance. Focusing hard in my shattered state, I maneuver through the three sets of lights with a last adrenaline surge. Once inside, the lagoon opens up and welcomes me into its calm embrace. I spot the fishing boat to the south. On my approach, Steve and his crew flash a spotlight and come over to help me tie up. A minute later Swell and I are secured to a blessed little orange buoy. I hug and thank them. My oceanic nightmare is over!

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit