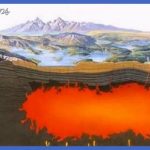

Snowmelt and rainfall provide the water by soaking into the ground locally and from the surrounding mountain ranges. The water flows deep into the geyser basin as groundwater, reaching many hundreds of feet (meters) below ground level, as shown in the diagram. The still-hot volcanic rocks found below Yellowstone’s geyser basins provide the source for heating the water. The rocks continually receive more heat where there is magma (molten rock) a few miles below. The plumbing that all geysers have consists of a vent connected to a narrow crack that goes down into the hot rocks, widening into chambers and narrowing into channels as it goes and intersecting a multitude of tiny cracks and pores that feed water into the geyser. What Happens to the Water Let’s follow the cycle at the point just after an eruption has ended. 1. The vent and crack have been largely emptied of water. A small part of the water that shot up into the air falls back into the geyser vent and drains down the crack. Of course, this water is much cooler than when it shot out. 2. More water now starts to fill the crack by seeping in from the sides.

This water is already very hot from having passed through hot rocks. Much hotter water enters the crack deeper down and pushes the overlying water up. Time-out here to mention three properties of hot water that clarify why geysers act as they do. The boiling temperature of water is higher at higher pressures. The weight of a column of water raises the pressure at the bottom, which raises the boiling temperature. This lets the hot rocks raise the water temperature, making it superheated water. The same weight of water occupies far more space as steam than it does as liquid water on the order of a thousand times more space. Superheated water flashes into steam if the pressure on it is lowered to ordinary atmospheric pressure. Now back inside the geyser: 3. As more water enters the crack (or fissure), the water level rises toward the surface. The added weight of water increases the pressure near the bottom. The hot water heats the somewhat cooler water already in the fissure. The water level rises past the very narrow parts of the vent. 4. As the superheated water continues to rise in the fissure, it starts to boil gently, forming small steam bubbles that rise and heat the overlying water. Figure 2.

How does a geyser work? Because the deeper boiling water is under higher pressure, it boils at higher temperature, and its steam heats the upper water to its boiling point. More bubbles form, raising the column of water and bubbles in the crack until it reaches the surface at the vent. Up to this point, the water pressure at depth has been increasing. 5. When water starts to spill out of the vent, the column of water in the fissure is at its greatest height. More steam bubbles from below displace liquid water, some of which spills out at the top. With more steam bubbles in the column now, the weight of the water becomes less, more boiling occurs, even below the constricted parts, and water comes out faster. 6. Next, the steam from below rushes through the constriction like jet engine exhaust. The water is being pushed rapidly toward the surface and spurts out. As more superheated water rises to the upper part of the water column, far more bubbles form, so the column has far more steam in it and thus less weight. This greatly reduces the pressure inside, letting the steam blow the water column out of the vent. The geyser is erupting an exponentially accelerating catastrophe! 7.

When all the steam has managed to escape from below the constriction, there’s nothing more to push on the water, and not much water there, so the eruption stops. Then the cycle begins again. There’s more about geysers in the Geological History chapter. Watching powerful Grand Geyser from close by is an unparalleled experience for its raw natural energy. Maybe the obligation to wait a long time in the hot sun (or in below-zero temperatures in the winter!) adds to the thrill when it does erupt, but it’s truly a stellar attraction. Grand erupts from a rather large vent a safe distance from the boardwalk and benches. Early in the park’s history, Grand erupted only at widely spaced intervals, but the interval gradually decreased between 1930 and the 1980s. In recent years, the range of time between eruptions is mostly from about 7 to about 10 hours. Your wait for Grand may be long, but it’s very likely to be rewarding, since Grand has become the world’s tallest predictable geyser. Don’t mistake Turban Geyser (the more impressive geyserite mound to the north of Grand) for the main attraction, although Turban will usually oblige you with 5 minutes of play about every 17 to 22 minutes.

The blobs of geyserite in its crater do resemble turban headdresses, but please don’t go off the boardwalk to get a closer look! Turban erupts about 5 feet (1.5 m) above its rim, except that for an hour or two after Grand has erupted, it may go to 20 feet (6 m). The relationship between Turban’s eruptions and the overflow and ebbing away of water in Grand’s pool can indicate how soon Grand will next erupt. Grand Geyser’s eruptions are always worth waiting for. When Turban erupts without lowering Grand’s pool, waves will begin to disturb the water surface more and more vigorously, and Grand’s eruption will usually begin. When Grand finally begins, a wonderful roaring from underground will accompany a tremendous burst of water up to 150 or 200 feet (45-60 m). But that’s not all Grand may put forth as many as four of these bursts or even more. Some people claim the first part of the second burst is always the most fun. Observer James C. Fennel wrote a description of Grand’s first burst in 1892 that’s valid years later. [W]ith earthshaking and tremendous rumbling that sounds like smothered thunder, the fountain without receiving warning of attack is shot aloft into the air two hundred feet in an immense column of steam and water. .

. . From the main column numberless jets are discharged at all heights and angles draping the Colossus in an agitated fringework of ever-changing patterns. . . . Vent Geyser next to Turban might be called Companion Geyser: its eruptions always accompany Grand and sometimes Turban. It erupts as high as 70 feet (21 m) at a slight angle and may continue after Grand’s eruption for an hour or more. In approximately the next quarter mile (0.4 km), there are only five named springs before the bridge over the Firehole. You pass springs connected to Grand called Economic Geyser (named for its habit of reclaiming almost all its erupted water), East Economic Geyser, and Wave Spring, and come to Beauty Pool and neighboring Chromatic Pool. Beauty and Chromatic pools illustrate extremely well the exchange of function between connected thermal features. Beauty Pool was for a time in recent years decidedly the more beautiful of the two, then in 1995 Chromatic Pool became hotter and therefore more colorful for about two months. The situation then reversed itself again and continues to do so. However, in the first years of Beauty Pool shows a full range of color in its water and bacterial mats (1996). the 21st century, neither pool has been at its best. Just across the Firehole bridge you’ll find Inkwell Spring, whose almost constantly bubbling water leaves inky stains on its cone from manganese oxide deposits.

The trail passes Oblong Geyser at quite a distance, due to the fact that Oblong can erupt as high as 25 feet (7.5 m) in a large boiling dome, pouring a huge volume of water into the Firehole River. You can infer its long history from the wide buildup of geyserite to Oblong’s west. Oblong has been active recently, with eruption intervals varying from about 3 to over 24 hours, but it goes through periodic dormancies. Oblong is known for the thumping noises it makes as it erupts. On a short spur to the right beyond Oblong you can visit Giant Geyser and its neighbors. This group is interdependent and connected to Grotto Geyser to the north as well. Some of the smaller features here are (left to right): Bijou Geyser (French for jewel), which plays almost constantly from its bacteria-cov-ered cone, Catfish Geyser, and Mastiff Geyser. Mastiff’s name may refer to its growling sound or to its watchdog function next to Giant. It has had periods of amazing energy. Usually Mastiff and Catfish have erupted simultaneously with Giant. Beginning in the middle of 1996, tremendous eruptions of Giant Geyser occurred frequently. Since 1955 there had been eruptions years apart, but for a time in the late 1990s and again from 2005 into 2008 they occurred a few days apart. Eruptions always occur during hot activity in Giant and its neighbors, but Giant Geyser displays its incredible power. nearby Grotto Geyser’s eruptions can take the energy Giant needs.

With eruptions sometimes reaching 250 feet (76 m), Giant has built a massive 12-foot-high cone (3.6 m) with an enormous central cavity. An estimated 1 million gallons of water (nearly 4 million L) pours out during an eruption. Giant Geyser ranks with the rarely erupting Excelsior and Steamboat Geyser as Yellowstone’s three most powerful. A short distance north of Giant, this route joins the paved walkway. Next, the bizarrely shaped Grotto Geyser is the central attraction. Grotto’s unique cone has probably been built up over fallen trees that became encrusted with geyser-ite. The interval between Grotto’s eruptions averages 6 or 7 hours but may be more than a day. It may erupt for an hour or perform a 36-hour marathon, height Grotto Geyser has the park’s most grotesque cone. about 15 feet (4.5m). It’s better to take Grotto’s picture when it’s not erupting, so that water and steam don’t obscure the view of its remarkable formation. Three geysers near Grotto erupt briefly just before or during Grotto’s long eruptions. They are Rocket Geyser, which erupts from its cone in unison with Grotto, sometimes up to 50 feet (15 m); Grotto Fountain Geyser, which can throw a thin stream of water up to 65 feet (20 m) and precedes most of Grotto’s eruptions; and smaller South Grotto Fountain Geyser, which also may erupt just before Grotto. The last two are far back from the walkway. Spa Geyser was named for the mineral spring in Belgium that gave its name to all such springs used for medicinal bathing. Don’t try bathing in this spa the water is over 190°F (88°C)! Spa’s infrequent but explosive eruptions, sometimes as much as 60 feet (18 m) high, are linked to Grotto’s activity.

The Sources and the Plumbing Yellowstone Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit

- Coolest Countries in the World to Visit

- Travel to Santorini, Greece

- Map of Barbados – Holiday in Barbados