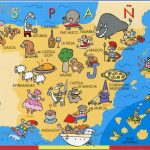

SPAIN (ESPANA)

Fiery flamenco dancers, noble bullfighters, and a rich history blending Christian and Islamic culture set Spain apart from the rest of Europe and draw almost 50 million tourists each year. The raging nightlife of Madrid, Barcelona, and the Balearic Islands has inspired the popular saying Spain never sleeps, yet the afternoon siestas of Andaluci’a attest the country’s laid-back, easy-going approach to life. Spain houses stunning Baroque, Mudejar, and Mozarabic cathedrals and palaces; hangs the works of Velasquez, Dali, and Picasso on its hallowed walls; and offers up a backyard of beauty with long sunny coastlines, snowy mountain peaks, and the dry, golden plains wandered by Don Quixote. You can do Spain in one week, one month, or one year. But you must do it at least once.

LIFE AND TIMES

HISTORY

IN THE BEGINNING (UNTIL AD 711). Spain was colonized by a succession of civilizations that have left their cultural mark Basque (considered indigenous), Tartesian, Iberian, Celtic, Greek, Phoenician, and Carthaginian before the Romans crashed the party in the 3rd century BC. Over nearly seven centuries, the Romans drastically altered the face and character of Spain, introducing their agricultural techniques and architecture, as well as the Latin language. A slew of Germanic tribes, including the Swabians and Vandals, swept over the region in the early 5th century AD, but the Visigoths, newly converted Christians, emerged above the rest. The Visigoths established their court at Barcelona in 415 and effectively ruled Spain for the next 300 years.

ONE WEEK Begin in southern Spain, exploring the Alhambra’s Moorish palaces in Granada (1 day; 906) and the mosque in Cordoba (1 day; 887). After two days in Madrid, travel east to Barcelona (2 days; 916) and the beaches of Costa Brava (1 day; 939).

BEST OF SPAIN, THREE WEEKS Begin in Madrid (3 days), with daytrips to El Esco-rial (873) and Valle de los Caidos (p.873). Take the high-speed train to Cordoba (2 days), and on to Seville (2 days; 887). Catch the bus to the white town of Arcos de la Frontera (1 day; 903) before heading south on the Costa del Sol, Marbella (1 day, 905). Head inland to Granada (2 days). Move along the coast to Valencia (1 day; 916). Then it’s up the coast to Barcelona (2 days), where worthwhile daytrips in Cataluna include Montserrat (938) and Figueres (939). From Barcelona, head to the beaches and tapas of San Sebastian (2 days; 946) and Bilbao (1 day; 956), home of the world-famous Guggenheim Museum.

MOORISH OCCUPATION (711-1469). Following Muslim unification and a victory tour through the Middle East and North Africa, a small force of Arabs, Berbers, and Syrians invaded Spain in 711. The Moors encountered little resistance, and the peninsula soon fell under the dominion of the caliphate of Damascus. These events precipitated the infusion of Muslim influence, which peaked in the 10th century. The Moors set up their Iberian capital in Cdrdoba (887). During Abderraman Ill’s rule in the 10th century, some considered Spain the wealthiest and most cultivated country in the world. Abderraman’s successor, Al Mansur, snuffed out all opposition within his extravagant court and undertook a series of military campaigns that climaxed with the destruction of Santiago de Compostela (959), a Christian holy city, in 997.

The turning point in Muslim-Christian relations came when Al Mansur died, leaving a power vacuum in Cordoba. At this point, the caliphate’s holdings shattered into petty states called taifas. With power less centralized, Christians were able to gain the upper hand. The Christian policy was official toleration of Muslims and Jews, which fostered a culture and even a style of art, Mudejar. Later, though, countless Moorish structures were ruined in the Reconquest, and numerous mosques were replaced by churches (like Cordoba’s Mezquita, 890).

THE CATHOLIC MONARCHS (1469-1516). In 1469, the marriage of Ferdinand de Aragon and Isabella de Castilla joined Iberia’s two mightiest Christian kingdoms. By 1492, the dynamic duo had captured Granada (906), the last Moorish stronghold, and shuttled Christopher Columbus off to explore the New World. By the 16th century, the pair had made Spain the world’s most powerful empire. The Catholic monarchs introduced the Inquisition in 1478, executing and burning heretics. The Spanish Inquisition’s aims were to strengthen the Church and unify Spain.

THE HABSBURG DYNASTY (1516-1713). The daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, Juana la Loca (the Mad), married Felipe el Hermoso (the Fair) of the powerful Habsburg dynasty. Felipe (who died playing a Basque ball game called cesta punta or jai-alai) and Juana (who refused to believe that he had died and dragged his corpse through the streets) produced Carlos I. Carlos, who went by Charles V in his capacity as the last official Holy Roman Emperor, reigned over an empire comprising modern-day Austria, Belgium, parts of Germany and Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the American colonies. Carlos did his part: as a good Catholic, he embroiled Spain in a war with Protestant France; as an art patron of superb taste, he nabbed Titian as his court painter; as a fashion plate, he introduced Spain to the Habsburg fashion of weaning only black.

But trouble was brewing among Protestants in the Netherlands. After Carlos I died, his son Felipe II was left to grapple with a multitude of rebellious territories. He annexed Portugal after its ailing King Henrique died in 1580. One year later the Dutch declared their independence from Spain, and Felipe began warring with the Protestants, spurring further tensions with England. The war with the British ground to a halt when Sir Francis Drake and bad weather buffeted the not-so-invin-cible Invincible Armada in 1588. His enthusiasm and much of his European empire sapped, Felipe retreated to his grim, newly built palace, El Escorial (873), and remained there through the last decade of his reign.

Felipe III, preoccupied with both religion and the finer aspects of life, allowed his favorite adviser, the Duque de Lerma, to hold the governmental reins. In 1609, Felipe III and the Duke expelled nearly 300,000 of Spain’s remaining Moors. Felipe IV painstakingly held the country together through his long, tumultuous reign. Emulating his great-grandfather Carlos I, Felipe IV patronized the arts and architecture. Then the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) broke out over Europe, and defending Catholicism drained Spain’s resources; the war ended with the marriage of Felipe TV’s daughter, Maria Teresa, and Louis XIV of France. Felipe’s successor Carlos II, the hechizado (bewitched), was epileptic and impotent, the product of inbreeding. From then on, little went right: Carlos II died, Spain fell into a depression, and cultural bankruptcy ensued.

KINGS, LIBERALS, AND DICTATORS (1713-1931). The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht seated Felipe V, a Bourbon family member and grandson of French King Louis XIV, on the Spanish throne. Felipe built huge, showy palaces (to mimic Versailles in France) and cultivated a flamboyant, debauched court. Despite his undisciplined example, the Bourbons who followed Felipe administered the Empire well, at last beginning to regain control of Spanish-American trade. They also constructed scores of new canals, roads, and organized settlements, and instituted agricultural reform and industrial expansion. Carlos III was probably Madrid’s finest leader, founding academies of art and science and generally beautifying the capital. Spain’s global standing recovered enough for it to team up with France to help the American colonies gain independence from Britain.

In 1808, Napoleon invaded Spain. The ensuing battles were particularly bloody. The French occupation ended when the Protestant Brits defeated the Corsican’s troops at Waterloo (1814). This victory led to the restoration of arch-reactionary Ferdinand VII. Galvanized by Ferdinand’s ineptitude and inspired by liberal ideas in the new constitution, most of Spain’s Latin American empire soon threw off its yoke, and declared independence. Lingering dreams of an empire were further curbed by the loss of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba to the US in the Spanish-American War of 1898. Upon Fernando VTTs death, parliamentary liberalism was restored and would dominate Spanish politics until Primo de Rivera came along in 1923. Rivera was brought to power in a military coup d’etat, after which he promptly dissolved Parliament and suspended the constitution. For almost a decade, he ruled Spain as dictator, but in 1930, having lost the support of his own army, he resigned.

SECOND REPUBLIC AND THE CIVIL WAR (1931-1939). In April 1931, King Alfonso XIII, disgraced by his support for Rivera, shamefully fled Spain, thus giving rise to the Second Republic (1931-1936). Republican Liberals and Socialists established safeguards for farmers and industrial workers, granted women’s suffrage, assured religious tolerance, and chipped away at traditional military dominance. National euphoria, however, faded fast. The 1933 elections split the Republican-Socialist coalition, in the process increasing the power of right-wing and Catholic parties. By 1936, radicals, anarchists, Socialists, and Republicans had formed a loosely federated alliance to win the next elections. But the victory was shortlived. Once Generalisimo Francisco Franco snatched control of the Spanish army, militarist uprisings ensued, and the nation plunged into war. The three-year Civil War (1936-1939) ignited worldwide ideological passions. Germany and Italy dropped troops, supplies, and munitions into Franco’s lap, while the stubbornly isolationist US and the war-weary European states were slow to aid the Republicans. The Soviet Union called for a Popular Front of Communists, Socialists, and other leftist sympathizers to battle Franco’s fascism. Soon, however, aid from the Soviet Union waned as Stalin began to see the benefits of an alliance with Hitler. Without international aid, Republican forces were cut off from supplies. Bombings, executions, combat, starvation, and disease took nearly 600,000 lives, and in 1939 Franco’s forces marched into Madrid and ended the war.

FRANCO AND THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY (1939-1998). Brain drain (as leading scientists, artists, and intellectuals emigrated or were assassinated en masse), worker dissatisfaction, student unrest, and international isolation characterized the first few decades of Franco’s dictatorship. In his old age, Franco tried to smooth international relations by joining NATO and encouraging tourism, but the national tragedy (as it was later called) did not officially end until Franco’s death in 1975. King Juan Carlos I, grandson of Alfonso XIII and a nominal Franco protege, carefully set out to undo Franco’s damage. In 1978, Spain adopted a constitution that led to the restoration of parliamentary government and regional autonomy.

After serving five years, Prime Minister Adolfo Suarez resigned in 1981, leaving the country vulnerable for an attempted coup d’etat on February 23, when a group of rebels took over Congress in an effort to impose a military-backed government. King Juan Carlos used his personal influence to convince the rebels to stand down, and order was restored. Charismatic Felipe Gonzalez led the Spanish Socialist Worker’s Party (PSOE) to victory in the 1982 elections. Gonzalez opened the Spanish economy and championed consensus policies, overseeing Spain’s integration into the European Community (now the European Union) in 1986. The years 1986 to 1990 were outstanding for Spain’s economy, as the nation enjoyed an average annual growth rate of 3.8%. By the end of 1993, however, recession had set in, and Gonzalez and the PSOE only barely maintained a majority in Parliament over the increasingly popular conservative Partido Popular (PP). Revelations of large-scale corruption led to the defeat of the Socialist party at the hands of the PP in 1994.

TODAY

The last several years have seen mixed progress in one of Spain’s most pressing areas of concern, Basque nationalism and terrorism. The militant Euskadi Ta Askatasuma (ETA) has committed numerous acts of terror in what they say is an effort to secure autonomy for Basque Country. On September 12,1998, the federal government called for an open dialogue between all parties and was endorsed by the Basque National Party (PNV). Six days later, ETA publicly declared a truce with the national government. On December 3,1999, however, ETA announced an end to the 14-month cease-fire due to lack of progress with negotiations. The past few years have seen instances of arson and a return of periodic terrorist murders of PP and PSOE members, journalists and army officers. In June 2002, authorities seized 288 pounds of dynamite near Valencia and charged that ETA was planning to strike tourist spots along the Mediterranean coast. That same month, controversy ensued when the Spanish Parliament moved to ban Batasuna, a pro-independence Basque political party that Aznar claimed is allied with ETA.

On a brighter note, the Spanish economy is currently improving. Over the past several years, unemployment has dropped drastically. Aznar envisions a new Spain in which the unemployment rate is even lower and more women join the workforce.

THE ARTS

Spain’s literary tradition first blossomed in the late Middle Ages (1000-1500). Fernando de Rojas’s The Celestina (1499), a tragicomic dialogue most noted for its folkloric witch character, helped pave the way for picaresque novels like Lazar Mo of Tormes (1554) and Guzman of Alfarache (1599), rags-to-riches stories about mischievous boys with good hearts. This literary form surfaced during Spain’s Golden Age (1492-1650). Poetry particularly thrived in this era. Some consider the sonnets and romances of Garcilaso de la Vega the most perfect ever written in Castilian. This period also produced outstanding dramas, including works

from Calderon de la Barca and Lope de Vega, who wrote nearly 2000 plays combined. Both espoused the Neoplatonic view of love, claiming that love always changes one’s life dramatically and eternally. The most famous work of Spanish literature is Miguel de Cervantes’s two-part Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605-15), which relates the satiric parable of the hapless Don Quixote and his sidekick, Sancho Panza, who think themselves bold caballeros (knights) out to save the world.

The 19th century bred a multiplicity of styles, from Jose Zorrilla’s romantic poems such as Don Juan Tenorio (1844) to the naturalistic novels of Leopoldo Alas (Clarfn). The modem literary era began with the Generacion del 1898, a group led by essayist Miguel de Unamuno and cultural critic Jose Ortega y Gasset. These nationalistic authors argued, through essays and novels, that each individual must spiritually and ideologically attain internal peace before society can do the same. The Generacion del 1927, a clique of experimental lyric poets who used Surrealist and vanguard poetry to express profound humanism included Jorge Guillen, Federico Garcia Lorca (assassinated at the start of the Civil War), Rafael Alberti, and Luis Cernuda. In the 20th century, the Nobel Committee has honored playwright and essayist Jacinto Benavente y Martinez (1922), poet Vicente Aleixandre (1977), and novelist Camilo Jose Cela (1989). Since the fall of the Fascist regime in 1975, an avant-garde spirit known as La Mov-ida has been reborn in Madrid. Ana Rossetti and Juana Castro led a new generation of erotic poets into the 1980s. With this newest group of poets, women are at the forefront of Spanish literature for the first time.

SPAIN ESPANA Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore Góra Kalwaria, Poland with this detailed map

- Explore Gumdag, Turkmenistan with this detailed map

- Explore Telfes im Stubai, Austria with this detailed map

- Explore Langenselbold, Germany with this detailed map

- Explore Krotoszyn, Poland with this detailed map