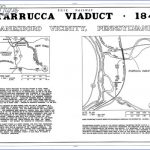

STARRUCCA VIADUCT BRIDGE MAP

The viaduct represents a milestone in North American stone vault engineering.

The most precious commodity in eighteenth-century Americaa new nation impatient to expand its frontierswas time. Stone bridges, though exceedingly strong and permanent, required time, and lots of it, to quarry, shape, and individually fit each piece. David Plowden notes in his classic survey, Bridges: The Spans of North America, that few of America’s rail lines were able to justify the high cost of stone bridges, an observation borne out by the fact that prior to 1850 only four significant masonry bridges had been built. These four viaducts the Carrollton (1829), Thomas (1835), Canton (1835), and Starrucca (1848) represent the finest examples of masonry construction in North America. The largest, the Starrucca Viaduct, is a monumental structure made graceful by its simple, slender proportions.

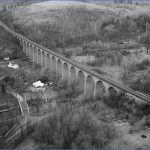

Its builder, the New York and Erie Railroad Company, was one of the largest economic enterprises of the time. It was incorporated in 1832 to build a line that by 1851 would stretch 484 miles (779 kilometers) from Piermont on the Hudson River to Dunkirk on Lake Eriea route determined by political, not economic, considerations. New York State approved the company’s charter on the condition that the line stay far from the Erie Canal, which ran from Buffalo to Albany; canal interests were powerful enough to force the railroad to build its route through difficult terrain along New York’s southern border. Although a number of surveys were made and abandoned before the final route was selected, the chosen route had its own obstacles. The biggest one, the deep valley at the Starrucca Creek at Lanesboro, Pennsylvania, brought work to a standstill in 1844 while engineers decided what to do.

STARRUCCA VIADUCT BRIDGE MAP Photo Gallery

Psychologically Americans were as temperamentally unsuited to build with stone as it was economically unfeasible for them to do so.

Julius W. Adams, from a family of prominent railroad builders and the supervising engineer of the New York and Erie line, designed the 1,040-foot (317-meter)-long viaduct. He was assisted by his brother-in-law, James P. Kirkwood, a Scottish engineer who had the experience needed to accomplish a masonry project of this magnitude and, it appears, the confidence as well. When asked if he could complete the job by 1848, Kirkwood is said to have replied, “I can… provided you don’t care how much it may cost.” Construction finally started in 1847.

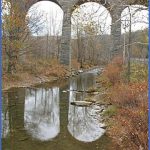

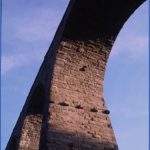

The Starrucca Viaduct is composed of eighteen semicircular arches, each with a span of 51 feet (16 meters), which rise on tapered piers 110 feet (34 meters) above the valley floor. The pier bases and roadway were made of concrete. The rest of the structure was constructed from local bluestone and brick. Kirkwood’s boast proved prophetic: the final cost of the lavish structure, completed in one year by eight hundred men, who were paid a dollar a day, was $320,000the most expensive railroad bridge ever built at that time.

GREAT BROAD OAUCE DOUBLE TRACK ROUTE;

An 1855 map of the New York and Erie Railroad’s network.

Both the time and the money were well spent, however. On December 9, 1848, the first locomotive crossed the double-track viaduct, and it has been in use ever since. The New York and Erie Railroad did not fare as well. In the 1860s, the line was dubbed “the Scarlet Woman of Wall Street,” a pawn in a series of underhanded financial schemes. A decade later, it suffered its fourth and final bankruptcy. Reorganized a number of times, the line emerged in 1960 as the Erie Lackawanna Railway Company, only to become bankrupt again in 1972. The line was taken over by Conrail in 1976.

The 19-by-40-foot (6-by-12-meter) footings for the thirteen full-height piers were concrete slabs made of cement from the Rosendale works in Ulster County, New York, representing the first documented use of concrete in America.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Explore East Lindfield, Australia with this detailed map

- Explore Bonferraro, Italy with this detailed map

- Explore Doncaster, United Kingdom with this detailed map

- Explore Arroyito, Argentina with this Detailed Map

- Explore Belin, Romania with this detailed map