Ai himself can be seen as on the mid-ground through his art production that often reflects the fact that he remains a profound nationalist’ (Smith 2011: 59) while his practice can be seen to be an expression of an erosion of nationally-perceived culture. His practice demonstrates a positioning within the mind space of urbaness as he both destroys (Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995) and reassembles chairs, tables and vases into new configurations (Table with Two Legs, 2004). The content, though, is drawn from a past, less dense, urban consciousness, full of culturally-bound Neolithic vases and Ming chairs and tables, as in the case of the two examples cited here. Nationalism and urbaness create an arrhythm within Ai’s practice, a discord that offers something quite different, not necessarily intended by the artist. As he reassembles, re-paints, rearranges, the underlying questions are embedded in his Chinese experience sitting side by side with his status as global man’ (Johnson 2011). It must be said that Ai appreciates arrhythmia, displaying a sense of transphilia or love of transience, symptomatic of contemporary times. This was most evident when Template, his 1997 Documenta 12 artwork consisting of wooden doors and windows from Ming and Qing Dynasty houses (1368-1911) collapsed. He declared that he liked it much better. His attitude reflects the playfulness of his early Dada-influenced works, but it is also recognition that the collapse transformed the work from a static object into an idea in motion.

Ai Weiwei: Methodology for possibilities

Ai’s practice sets up structures that make room for possibilities’ (Ai cited in Bingham 2010: 11) rather than definitive statements and creates what Lefebvre called moments’ of change, Debord called chance and Koolhaas calls exacerbated difference. Within this practice Ai creates moments of connection between disparate and unexpected actions and objects that disturb and transform the status quo. Ai’s Sunflower Seeds at the TATE Modern, London, UK 2010 and his Fairytale at Documenta 12, Kassel, Germany 2007 both demonstrate this practice. As in Lefebvre’s theoretical inquiry, Ai’s practice in both Sunflower Seeds and Fairytale reveals multiple philosophical layers of intention combined with political overlays that reflect his consciousness on a shifting mid-ground. At one level both art works address issues of Chinese culture and politics; at another level the works are symbolic of a worldwide shift in consciousness that could only have been imagined and undertaken in an urban century. Within this context Ai’s practice is enigmatic and contradictory in that it is part of an unfinished process. Sunflower Seeds consists of one hundred million porcelain seeds, hand painted by 16,000 artisans from Jingdezhen city where Imperial porcelain was produced. The devaluation of the individual within the mass is central to Ai’s intention, as is the reference to Mao’s countless portraits that incorporate sunflowers. At the same time the number of seeds in the Turbine Hall in London perhaps inadvertently connects the viewer’s mind to contemporary revolutions’ in the Middle East and the implications these may have for China. Fairytale is also a multi-layered work. By transporting 1,001 people from various backgrounds from cities across China to Kassel, the German Documenta city, Ai again highlights questions of individual and mass within the Chinese context while almost inadvertently employing a transient practice seeped in arrhythmia. This was most evident in the continuous movement and re-assemblage of the 1,001 chairs by visitors to Documenta 12 and in the random movement of Chinese people across the city of Kassel.

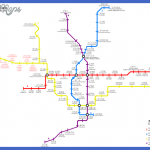

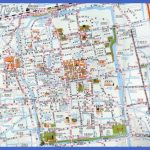

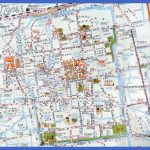

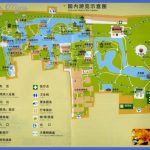

Glazed clay tiles depicted peasants at work, horses and camels Suzhou Subway Map at rest. At their peak they were using coins, gold leaf, fine porcelain dishes Suzhou Subway Map and in the town museum I’d seen a ceremonial crown of delicately-wrought metal shaped into birds and snakes, set on a headband with many strings of metal beads hanging from it. An impressive item. The tombs are scattered over a vast area and I only managed to reach three of them. One has the remains of a walled enclosure, and on all three the exterior brickwork is eroded into deep crevices full of nesting birds. The ground is littered with broken fragments of pottery.

Suzhou Subway Map Photo Gallery

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- The Best Cities To Visit in The World