Autonomy Afar Pedaling Daydreams

The trade winds whisper across my ears as I push the bike pedals and swerve between mud puddles. Gaspar finally sailed away two weeks ago, so I’ve had time to explore and meet the locals. I don’t know if I’ll ever see him again, and I’m thankful we parted on good terms. I held tight to Melanie’s wisdom, and stayed patient for the most part but came away convinced, yet again, that I prefer to be solo for now.

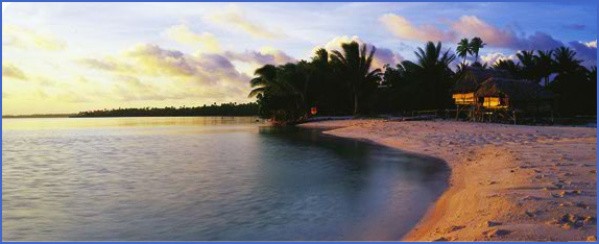

The road winds through a thick palm forest to a village farther north. Overhead, the tall trees nod and rustle, as if gossiping while I pass. Where their shadows stop, the equatorial sun is oppressive. I wipe the sweat from my brow, suck at the steamy air, and keep pedaling. When the road cuts closer to the lagoon, hues of milky turquoise stack up behind the arcing trunks of the palms that lean deeply over the lagoon’s edge.

I’ve spent a lot of time marveling at the paradisaical scenery here, which contrasts with the harsh realities of life that I’ve encountered. Without foreign aid, easily cured illnesses go untreated. Kids suffer with horrible skin rashes and chronic diarrhea from the polluted drinking water. Their arms and legs are covered in scars from bug bites. Education is limited to elementary levels. Stories of birthing and infant deaths and amputations are frequent.

Travel to Kiribati Photo Gallery

Being a woman here looks tough. Domestic violence and incest are normal. Women are men’s possessions, useful for sex, sweeping, weaving, cooking, washing, sewing, hauling water, and raising children. They also collect the seaweed for drying, pandanus leaves for weaving, and coconut husks for cooking. They bathe fully clothed in the brackish groundwater because there is no privacy. Coconut fiber and rags are used for menstruation. Lice infestations are rampant. Items like elastic hair ties, tampons, shampoo and conditioner, washing machines, baby wipes, and strollers don’t exist. Women gather in big circles under each village’s open-air, tin-roofed meeting house, or maneaba, sewing together old tarps or rice bags to make sails, twisting coconut fibers into rope, making hand brooms, or weaving hats, bags, and sleeping mats from dried pandanus leaves.

Frankly, being a man doesn’t look much easier. They make constant home repairs, go fishing in the blazing tropical sun, and dry copra one of the few ways to earn money by collecting mature brown coconuts in the forest, hauling them home by the dozens, splitting them open (with a hatchet if your family is lucky enough to own one), then laying the open halves out to dry in the sun. After three or four days of praying it doesn’t rain, they dislodge the dried meat from the coconut shell and load it into sacks. Captains from the few passing ships then purchase the sacks by weight. With seafood as a dietary staple here, fishing is life. The men go trolling on their sailing canoes with one hand on the rudder, one hand on the line that trims the sail, with the nylon fishing line wrapped around their big toe. The canoes are anything but sturdy or stable, but they wrangle huge tuna and game fish. There are no VHF radios, no Coast Guard, no life rafts to get in if the canoe cracks or they are blown too far offshore. But despite the perpetual discomfort, back-breaking work, and constant uncertainty, the I-Kiribati generally seem lighthearted. They exude a live-for-the-day feeling that makes life seem less serious. Heck, why make a big deal, when a fever could kill you tomorrow!

No matter how long it takes for the supply boat to show up, the I-Kiribati will endure. They eat everything that moves: fish, sharks, turtles, dogs, seabirds and they know how to laugh. The best jokers are revered, and rightly so: Laughing makes hunger, pain, monotony, or sadness a little easier to bear.

I grow thirsty, pull off the road, and wander through the coconut grove with my eyes cast skyward. My fingers begin to tingle with excitement when I spot a choice young bunch of green coconuts. The climb takes absolute concentration. I grip around the back of the trunk and walk my bare feet up the front. At the top, I collapse into a tight hug of the trunk, then twist two coconuts from the bunch and drop them gingerly. My knee-length shorts allow me to slide straight down. After opening the coconuts with a knife, I suck down the sweet liquid and hop back on my bike.

Kiakias freckle the roadside as I approach a village. The glare off the roof of the maneaba is blinding as I pull over into its shade. Independence Day festivities are only a month away and every islander is busy. The women sit, lean, or lie among heaps of loose plant fibers. They are making elaborate, double-layered grass skirts for dancing. My friend Taurenga sets a plate of dried bananas in front of me as I join the circle.

“Ko rabwa” (Thank you), I reply with an appreciative nod. The women tease and bicker over whose son will sail away as my husband. I only understand what Taurenga can translate. Their laughter is delightfully unchecked flooding the maneaba with boisterous cackles and belly laughs. I stand up with one of the finished skirts, tie it around my waist, and try to mimic their dancing. They hoot with hilarity.

“You no I-Matang, you I-Kiribati woman!” one woman cries, rising to her feet to dance too. I feel safe and happy here with them. Their inner beauty and confidence radiate so strongly that missing teeth or body shape or hairs on a chin are meaningless. “Beauty” itself takes a new shape in my mind from being near them. An hour passes and I pull out some DVDs and a mix of medical supplies to leave with them. As far as it feels from modern civilization, the people here love watching movies. Families gather around a communal TV at the maneaba. I wave goodbye to everyone and carry on. It’s after 3 pm, and the kids will already be in the water.

Near a grassy trail, I stash my bike in the bushes and wander out to the beach.

Squinting into the afternoon sun, I’m happy to see small swell-lines marching into the bay.

“Leees! Leees!” little Nato shouts, running toward me with a frantic smile. At least ten little boys leap and frolic in the waves that wedge up at the end of a half-submerged jetty. The boys run out over the cracked cement blocks of the WWII remnant, and hurl themselves off the end into an approaching wave face. They ride flat wooden planks or old bodyboard cadavers all the way to shore. Half of them are naked. The other half wear hand-sewn shorts, often ripped or too big. They trade off with the plywood or foam, because there aren’t enough for everyone. I join the loop, run out the jetty wall, and leap into a wedging right, bodysurfing it in. Washing up, they laugh and scream and pat me. I take a few more and then sit with the pack of girls gathered by the bushes to watch. I wish they would come put their feet in the sea, but it’s taboo for females here. Even though I despise this disparity, I don’t feel it’s my place to challenge their customs. In fact, I know there is much to learn from them. My eyes well up when I watch Nato pass his square of plywood off to the youngest boy, who has been waiting patiently for a turn. They hug each other in excitement before the little dude skips wildly out the jetty.

Lucky Hearts

“Is she going to vomit?” asks Teaboka, the youngest of the three fishermen, in Gilbertese. As we motor away from Swell in the twelve-foot tinny, Teuta, Nato’s father, translates his question with a cracked-tooth grin. It’s obvious Teaboka isn’t thrilled about adding my company to their weekly Saturday fishing expedition. I’m not so sure either. We’re headed offshore in this easily sinkable aluminum boat with an outboard motor that looks like it’s past its prime.

“Does he know I sailed here?” I reply.

“It because Kiribati people believe women bring bad luck on the sea,” he answers. I roll my eyes. I think it’s more likely that women aboard cause competition for the men and thus, complication. Teuta laughs as the boat bounces toward the rocky shore in the drizzling rain. We land on the beach, and Beeto and Teuta search for the roundest coral stones lining the water’s edge. I take note of the desired specs and hunt too. Teaboka takes off toward a cluster of bushes, returning with a stack of large round leaves and a hatful of hermit crabs. When our empty rice bag is nearly filled with stones, we pile aboard and head out the pass.

It feels good to be in open waters after almost six weeks at anchor, although I’m not fully awake. The squalls and pummeling rain had kept me up through the night. I’d tossed and turned, regretting my request to go fishing the night before at dinner with Nato’s family. The weather is still stormy, and Kiribati fishermen are regularly lost at sea. What if the engine dies?

Maybe You Like Them Too

- Top 10 Islands You Can Buy

- Top 10 Underrated Asian Cities 2023

- Top 10 Reasons Upsizing Will Be a Huge Travel Trend

- Top 10 Scuba Diving Destinations

- World’s 10 Best Places To Visit